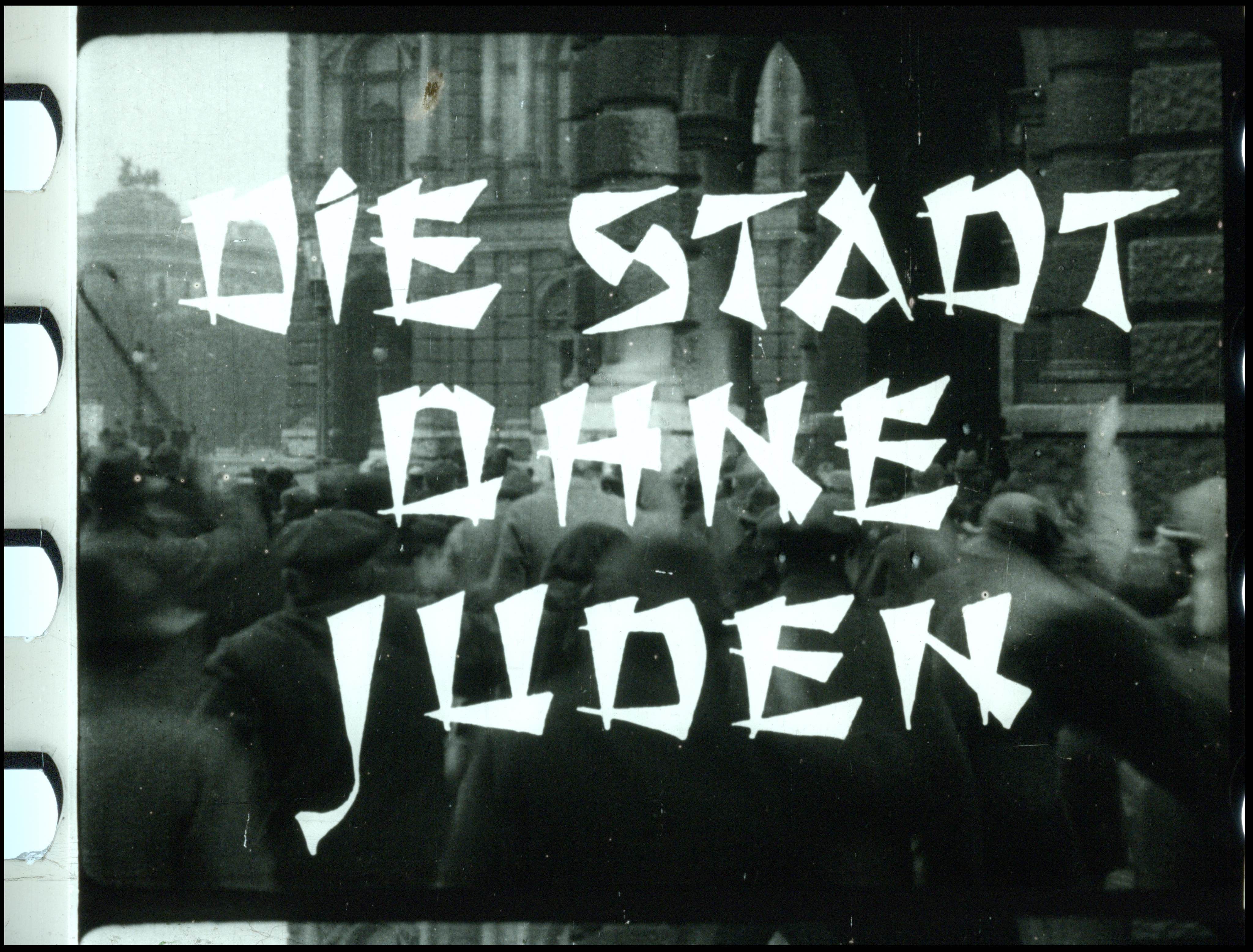

The Rediscovery of a 1920s Silent Film Predicting the Rise of Nazism

“The City Without Jews” is returning to cinemas for the first time in decades.

When the silent film The City Without Jews first aired in New York in July 1928, it was panned by the city’s papers. The New York Times described it as “one of the most fatuous productions imaginable,” with “a title to attract attention, but … no problems, no acting above subnormal, no interesting situations and no unusual photographer.” The critic professed to have no idea as to “why the Fifth Avenue Playhouse volunteered to bleed and die, if need be, in order to get it.”

Yet while the film’s plot might have seemed ludicrous to some audience members in the 1920s, to many modern watchers, its events are eerily prophetic. First released in 1924, The City Without Jews is an Austrian expressionist film, based off the satirical novel of the same name by the novelist and journalist Hugo Bettauer. It predicts a future in which Jews are forcibly expelled from their homes in an unnamed European city and piled into stock car trains, before being shipped east, and out of the country.

The film had been lost for decades before being found in a Paris flea market in 2015, the BBC reports. Now, after a major crowdfunding campaign from Austria’s national film archive, it is being screened in cinemas across Europe for the first time in as much as 80 years, starting in Vienna, Austria.

When the novel and film were released, “at the beginning of the 1920s, just after Austria’s First Republic was founded, political anti-Semitism was growing incredibly, much more than during the monarchy,” Nikolaus Wostry, director of collections at the Filmarchiv Austria, told the BBC. “That all brought [Bettauer] into big conflicts with the right wing in Austrian society, which was quite dominant at that time.”

In the novel, and subsequent film, the city’s citizens initially celebrate the departure of the Jews, who had become political scapegoats for the city’s rising unemployment and prices. But there’s a happy ending, of sorts: As the economy begins to crash down, with theaters going bankrupt and other businesses suffering, a popular movement demanding the Jews’ return gains pace; the proto-fascist party in power falls; and the expulsion law is repealed. The film ends, however, with the revelation that the entirety of the plot has been a dream. The anti-Semitic Councillor Bernard awakens with the sudden revelation that the Jews, in fact, are a “necessary evil.”

Bettauer intended his novel to be controversial. Born to a Jewish family in Austria, he spent much of his life in the United States and abroad, after running away to Alexandria, Egypt at the age of 16. At 18, he converted to Christianity. He was, in many respects, a political radical, variously being expelled from Prussia for exposing police corruption; arguing for legalized abortion; and supporting the rights of gay people. This novel was an attempt to skewer what he perceived to be a growing current of racism and intolerance in Viennese society, aimed at a popular audience. “As both a journalist and an author,” writes the scholar Kenneth R. Janken, “he understood how to combine capitalistic forms of publishing and entertainment with socially relevant and progressive ideas.”

The book was hugely successful, and sold more than 250,000 copies. The film, though popular, performed less well with audiences, and has since been considered one of the most overtly anti-Nazi films of its time. Its screenings were sometimes the site of protests by Nazis, where stinkbombs were thrown into the audience. For Bettauer personally, the film’s release provoked a major hate campaign, Wostry said. “His private address was published and in the newspapers, it was explicitly said that such a person shouldn’t be part of society.” In 1925, he was murdered by a young member of the Nazi party, Otto Rothstock, who claimed to have killed Bettauer “to save German culture from Jewish degeneration.” He was declared insane, but served only 18 months in a psychiatric institution.

The film’s release this year does not take place in a political vacuum, Wostry told the Washington Post. “In today’s Europe, we can clearly see the exploitation of people’s fears once again,” Wostry said. “Politicians focus them on target groups—be it immigrants or followers of religions. And as Austrians, we have a special responsibility.” Recent allegations of and investigations into anti-Semitism across Europe provide part of that backdrop, the Post reported, while the success of the film’s crowdfunding may, in part, have been a response to political events across the globe. “We received enormous financial support from abroad,” Wostry said, “including from Americans following the 2016 U.S. election.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook