The Doomed Blind Botanist Who Brought Poetry to Plant Description

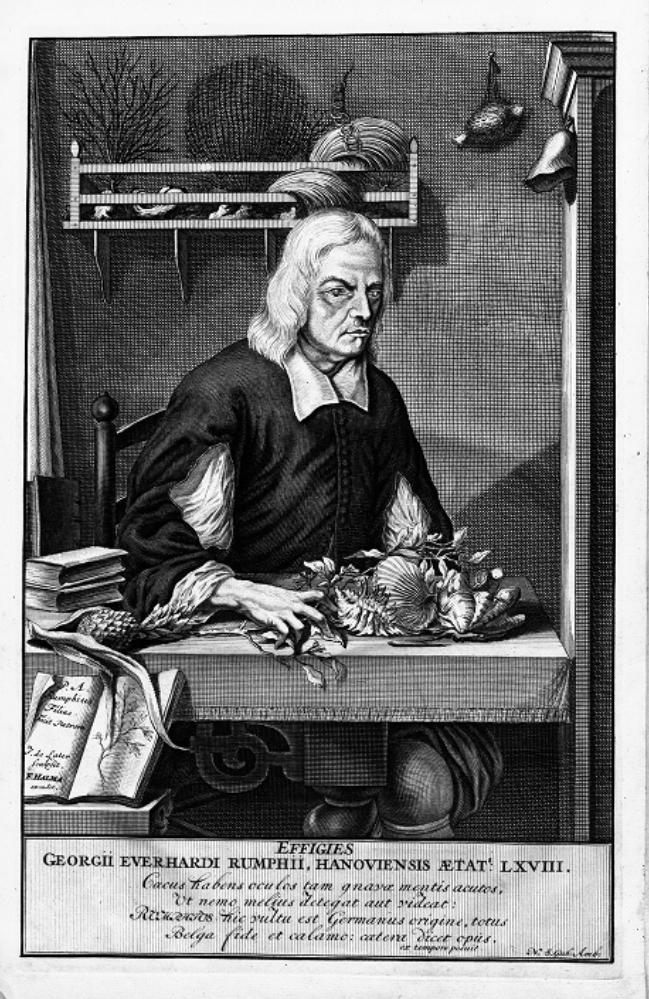

A portrait of Rumphius from his book. (Photo:Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Somewhere in the great southern ocean that stretches south from Java there is a tree that grows straight out of the ocean floor. Its name is Pausengi, and it sits in the axis of the world. A terrible whirlpool surrounds the trunk of this tree, drawing in any ship that sails too close to it. In its branches rests the Garuda, half-man and half-eagle. Every night, it flies north, and returns with an elephant, tiger, rhinoceros or other large beast in its claws. The few sailors who have survived the Pausengi’s whirlpool flew home by hanging on to the Garuda’s feathers.

The story of the Pausengi tree and its marvelous fruit–traditionally believed to be an antidote to all poisons– appear in book 12 of the Ambonese Herbal, a vast work of botanical knowledge from the tropics compiled in the latter half of the 17th century by the great German naturalist Georg Everhard Rumpf during his decades of residence on Ambon, an island in what is now eastern Indonesia. In telling this story Rumpf (who preferred to go by Rumphius, the Latinate spelling of his name) was trying to solve a botanical mystery.

Every so often, giant coconuts would wash up on the beaches of the Spice Islands, shaped very much like men’s buttocks. No one had ever seen the plant that gave rise to them. As a consequence, they attracted many legends, several of which Rumphius recorded. Rumphius himself didn’t believe the story of the Pausengi tree. He thought that the sea coconuts, or cocos-de-mer, must come from some unknown land.

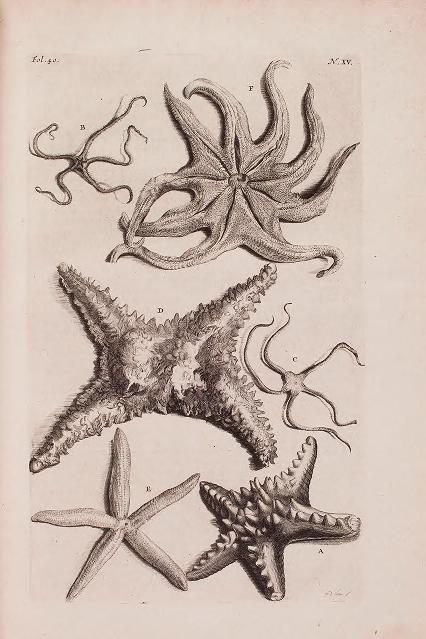

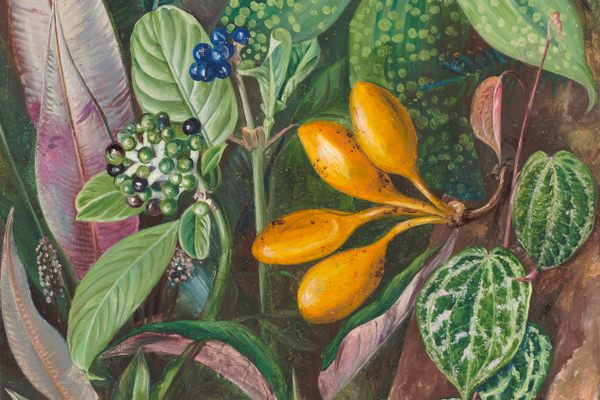

An illustration from Georg Eberhard Rumphius’ work Ambonese Herbal. (Photo: Internet Archive)

We now know that he was right: the coco-de-mers grow on a rare type of palm found only on the Seychelles, an island chain not yet explored in Rumphius’ day. These palms grow very tall and take many years to flower and bear fruit. (According to the poet Octavio Paz, its spadix is “shaped like a phallus, measures three feet in length, and smells like a rat”). Each nut weighs over 40 pounds. After they germinate, their empty shells float across the open ocean, posing a puzzle to all who find them.

The mix of fact, folklore, legend and speculation in Rumphius’ entry on the sea coconut is typical of his work. He lived at a time when the boundaries between disciplines hadn’t yet been clearly drawn. He was much an ethnographer as a biologist, as much a linguist as a scientist. In compiling his many works of geography, linguistics and natural history (the Ambonese Herbal alone runs to six thick volumes), he relied on local informants to furnish him with specimens and brief him on their medicinal properties. He completed this titanic work in spite of blindness and personal tragedy. Most of it was published long after his death. Given the various disasters that befell his manuscripts, it’s a miracle it appeared at all.

Rumphius was born in 1627, in Hanau, Germany, into the fury of the Thirty Years War. His father was a builder who taught his son mathematics, Latin and draftsmanship. When he was 18, Rumphius joined a mercenary force. Tricked by an aristocratic soul-merchant, he thought he was going to fight for Venice, but found himself languishing in Portugal for three years instead. In 1649 Rumphius returned to Germany. Three years later, he signed up with the Dutch East India Company and shipped out for good. In 1653 he arrived in Batavia on Java, before settling in Ambon, the main trading center of the Moluccas, or Spice Islands, which he never left again.

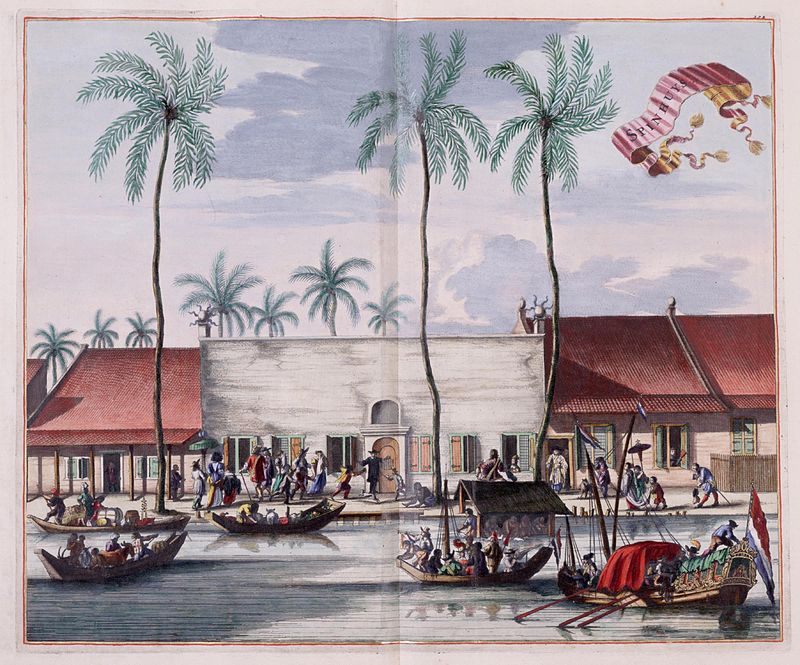

A scene showing Dutch settlement in Batavia (now Jakarta), c. 1665. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Living on Ambon, Rumphius was soon confronted with the dizzying variety of tropical life. He set about making as comprehensive a catalogue of species as he could. His life was one of relentless activity punctuated by terrible misfortune. In 1670, at the age of 43, he went blind. In 1674, a terrible earthquake struck Ambon, which claimed the life of his wife and two of his children. An accompanying tsunami swept away the village on the north coast where he had long lived and worked as a trader.

That day, Rumphius and his family had gone to the Ambon’s Chinese quarter to see the celebration of the New Year. His wife and two daughters went into a store while Rumphius stayed outside. When the earthquake struck, they were trapped inside. A witness describes him shortly thereafter, sitting next to their bodies: “It was full piteous to see that man sit next to these his corpses, as well as to hear his lamentations concerning both his accident and his blindness.”

In time, Rumphius remarried and returned to work, helped by his son and hired scribes. In 1687, a fire burnt down his house, and with it, his library and most of his manuscripts and drawings. Against his wishes, he was forced to sell his collection of curiosities to a Medici prince. Years later, when he had finally reconstructed the manuscripts, he sent them away to Amsterdam to be published. A French squadron attacked the ship they were on, which burned and sank. The work only survived because another nature-lover on Java had a personal copy made before they set out.

When his manuscript finally did arrive in Amsterdam, the Dutch East India Company decided that it contained too much secret information, and prohibited it from going into print. The Herbal did not get published for another 50 years.

Rumphius’ Ambon house, photographed c. 1910. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In setting about his great work, Rumphius’ first task was one of naming. For each plant and shell in his collection, he would list its name in Latin, Malay, Ambonese, and, when possible, Javanese, Hindi, Portuguese and Chinese as well. He also had to invent names in his adopted language, Dutch. He took on this burden with all the exuberance of a new Adam. A tour through Rumphius’ work is a masterclass in the poetry of the concrete noun. His shells bear names like Little Dream Horn, the Prince’s Funeral, Peasant Music and the Double Venus Harp.

His plant names are even more adventurous. In the pages of his Herbal, one meets, among others, the Writer’s Fern, the Nude Tree, the Adultery Plant, the Blue Clitoris Flower, the Memory Plant, the Astonishment Plant, the Wondrous Quis-Qualis Shrub, the Bilious Rope, Stinking Bindweed, Redolent Conyza, Saturn’s Beard, Hair of Nymphs, the Wild Drumstick Tree, Eyes of the Sea Crabs, the Mountain Fish-Slayer Tree, the Blinding Shrub, the Berries-Bearing Tuba Shrub, the Notched Appendage, and the Tart Rottangh.

Rumphius did not stop at naming. He described each plant’s structures, the shape of their roots, arrangement of their leaves, and color of their flowers. He attempted, for every plant in his collection, all its possible uses, from commercial to medical to romantic. He wrote which plants were good for diarrhea, which cured jaundice, which soothed childbirth and which inflamed the passions of Venus. When he could, he also listed what various plants meant in the secret language of the women of Ambon, who used herbs to signal who they loved and whom they despised.

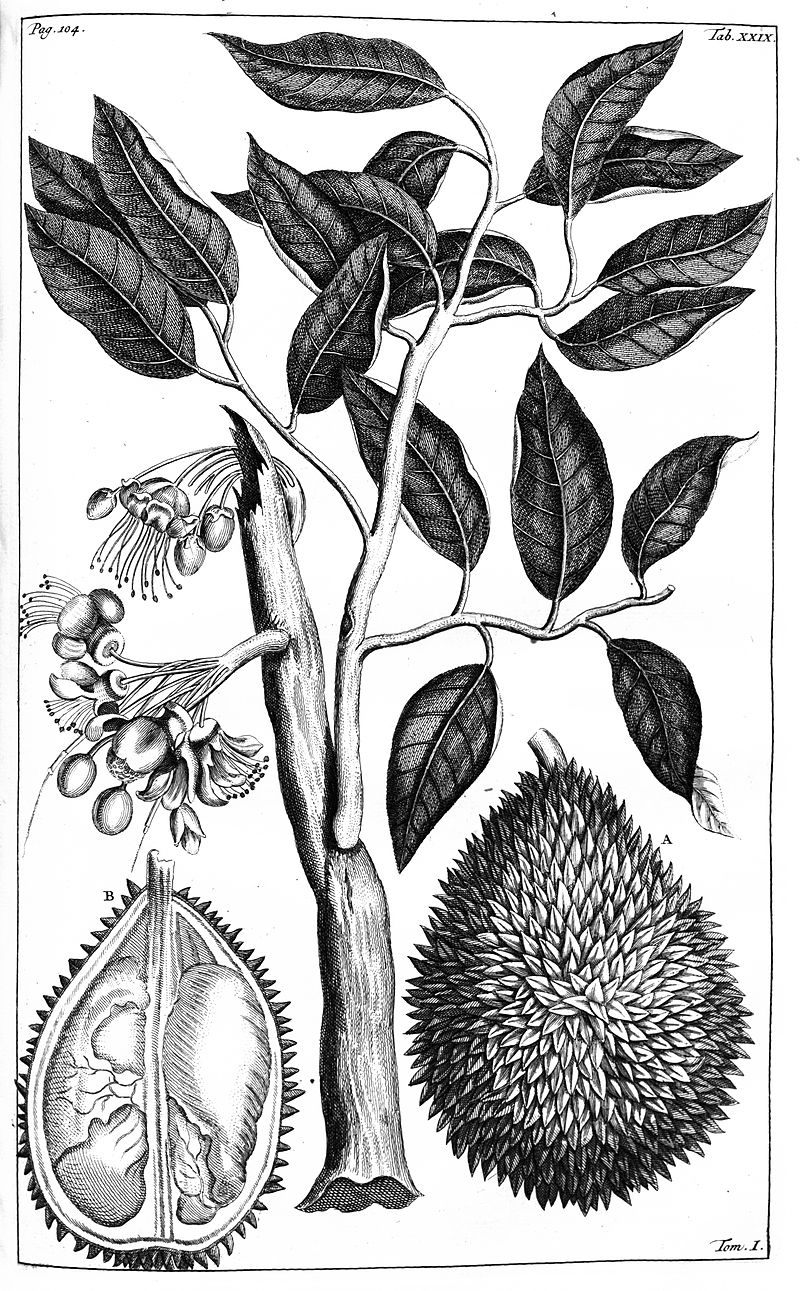

Rumphius’ depiction of a durian. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Unable to see, Rumphius relied on his others senses to describe the natural world. He felt the difference between snails with his fingers, and noted the mild and luscious flavor of the durian, “not unlike egg custards,” and the “dry, astringent” taste of the Crocodile Leaf. He had a remarkable memory for color, and a gift for metaphor, which kept images alive in his mind. He wrote of tiny crabs that “walk on the sea like foam,” and troublesome hermit crabs who were always taking his favorite shells for homes, “leaving me their old coats to peep at.”

Though he spent much of his time describing plants, he may have loved the life of the sea best, and above all those species like marine snails and jellyfish which were of no practical worth to anyone. It is in writing of these that his language takes fullest flight. Describing a Portuguese Man-of-War, he wrote that “the body is of a transparent color, as if it were a crystal bottle filled with that green and blue Aqua Fortis.”

Of a marine snail called a Purple Sailor, which would sometimes would congregate in great numbers on the surface of the sea, Rumphius wrote that it was “wondrous to see, such a fleet of easily a thousand little ships, that could sail so agreeably together.” If one were to take one of these snails out of the water, it would stay alive for a day or so in a dish of water, “emitting a wondrously beautiful repercussion of light, as if the dish were filled with Precious stones.”

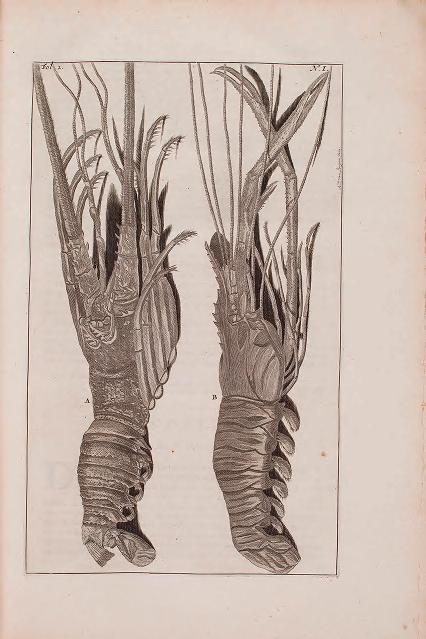

A depiction of lobsters from Ambonese Herbal. (Photo: Internet Archive)

Rumphius mentions his personal life in his work, but only rarely. We know the name of his first wife because he named an orchid after her. After describing the arrangement of its stems and leaves, the shape of its root and the structure of its flower, he mentions that this particular blossom has no native Malay or Ambonese name. Therefore, he decided to name it the Susanna Flower, “in memory of her who when alive was my prime Companion and help-meet in the gathering of herbs and plants, and who was the first ever to show it to me.”

Rumphius writes of the earthquake that killed Susanna and his daughters in the course of introducing the subject of corals. After listing the various names the Chinese have for corals, which he calls “Seatrees,” he pauses to insert a brief poem about the “dread and quaking day” when they were all exposed to the air. He writes that the earthquake came with a “fearful noise” and a “cracking of mountains,” and continued with the “bursting and tumbling of rocks as if the whole world were going to burst asunder.”

He then remembers three terrible waves, which he never saw. They rose out of a “whirlpool of Sulphur” and “stood tall like walls, fiery and white on top and black below.” Coming ashore, they carried away everything in their path, people, cattle, and houses alike. When they receded into the sea, they left the land stripped as bare as if it had been swept with a broom.

This article owes a great debt to E.M. Beekman’s colossal work of scholarship translating and annotating Rumphius’ work over many years.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook