The Founding Fathers’ Favorite Mastodon Is Coming Home for a Visit

Here’s how you ship the skeleton of long-dead megafauna across the Atlantic.

Eleanor Harvey knew that she wanted to bring the mastodon back to America, where it had lived, roamed, and died by the close of the Pleistocene. She just wasn’t sure it was possible. How do you cart a half-ton, long-dead elephant cousin from Germany across the Atlantic and into a gallery? How do you even get it through the doors?

Harvey, a senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, in Washington, D.C., is mounting an exhibition opening in spring 2020 about Alexander von Humboldt, the 19th-century naturalist whose fascination with climate, taxonomy, and other fields of study profoundly influenced scores of researchers. Harvey had compiled a list of paintings, sculptures, maps, and other artifacts that testify to Humboldt’s legacy. But she also wanted the bones.

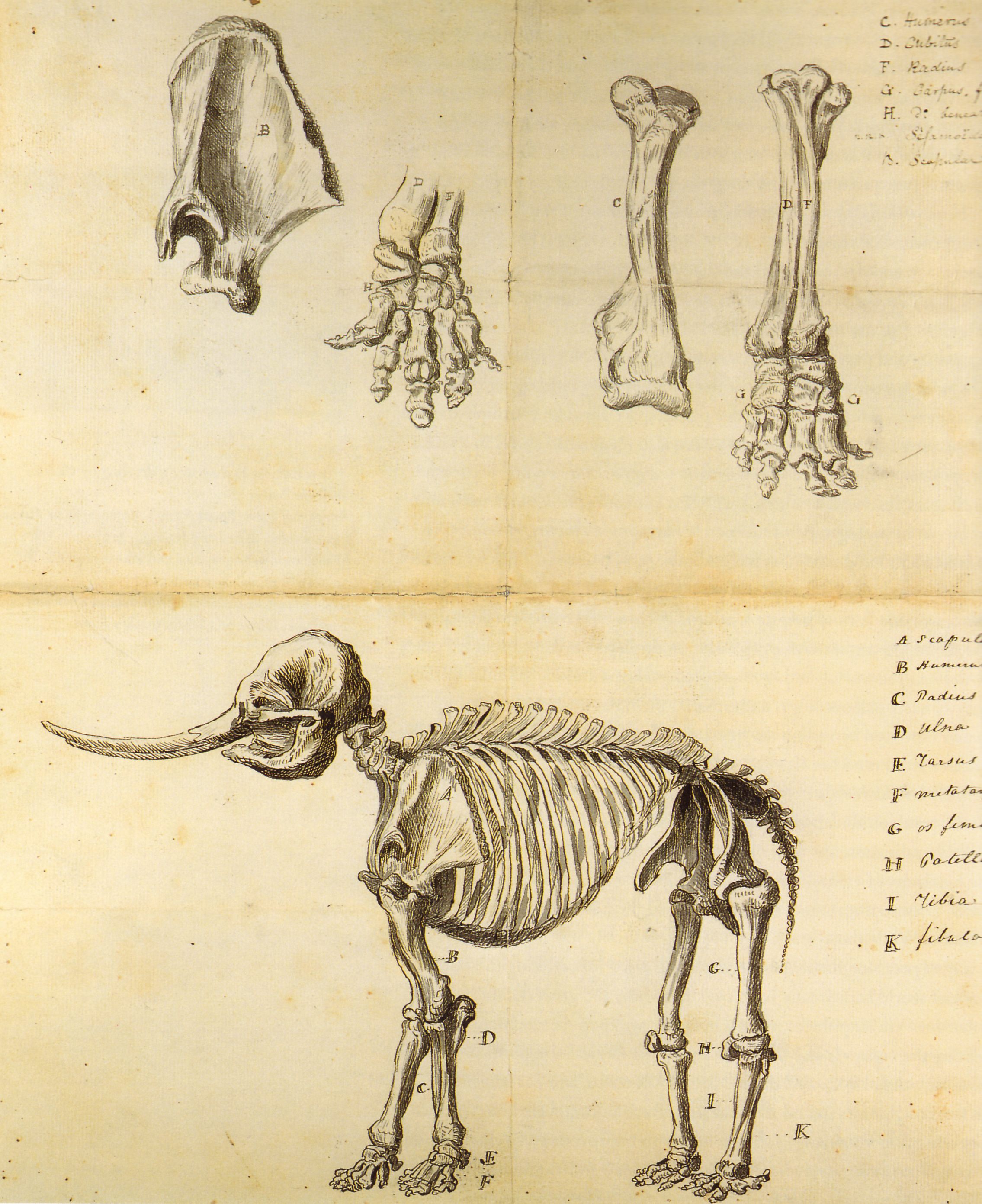

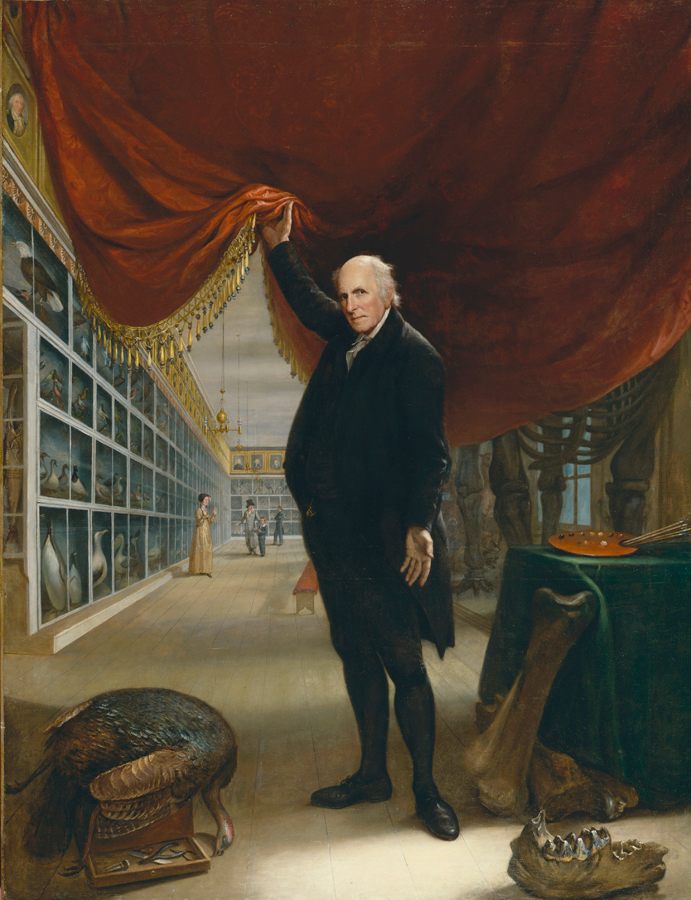

That’s because these aren’t any old mastodon bones. They’re what’s left of the creature sometimes known as “Peale’s mastodon,” an American mastodon (Mammut americanum) named for the painter, naturalist, and Philadelphia Museum curator Charles Willson Peale, who rushed to Newburgh, New York, in 1801 and recruited more than two dozen others to help pull the gargantuan fossils from the ground.

It wasn’t so unusual to come across a monumental mandible or hulking rib: Mastodons and mammoths once ranged across North America, and proof of their presence is still buried in fields and streams. This particular skeleton became especially famous, though—maybe more for its place in historical anecdotes than for any unique scientific value.

Before the bones wound up in Europe—where they’ve spent over 100 years winding through England, France, and Germany, and came to rest in the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt—they were powerful symbols of an America still finding its way. The country was young, and many detractors viewed America as a kind of Diet Europe—less robust, less appealing, just a little bit worse all around.

This really chafed Thomas Jefferson. The politician was also a passionate naturalist, and he was fed up with the arguments advanced by people like the French naturalist and polymath Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, who insisted on a “Theory of American Degeneracy”—an argument, published in his hefty, multivolume Histoire Naturelle, that outlined how life in the New World blunted and stunted people and other creatures until they were puny, weak, and irredeemably unimpressive.

In the face of this scientific sneering, Jefferson was delighted by mastodon bones (though he, and most everyone else at the time, thought they were mammoths). They were huge! They were awe-inspiring! They were proof that America was built on a foundation of giants that made the ground shiver when they strode across it!

In his Notes on the State of Virginia, written in the 1780s, Jefferson trampled on Buffon’s theory, writing, “the bones of the mammoth which have been found in America are as large as those found in the old world.” He was keen to find more.

What America lacked in centuries-old cathedrals or imperial ruins, it made up for in bones. So celebrating the megafauna became a patriotic project. “There’s a huge amount of civic pride attached to this mastodon skeleton,” Harvey says. “Jefferson [was] pinning America’s robustness to natural landmarks and this gigantic skeleton.” Jefferson even helped usher in the use of “mammoth” as an adjective to describe something remarkably massive.

Dinosaurs hadn’t really been excavated yet. Though bones had turned up even in antiquity, they were largely attributed to giants or monsters until later in the 19th century, when digs in the English countryside revealed bones linked to ancient reptiles, according to Mark A. Norell, a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History. So, in Peale’s day, some thought the mastodon might be the biggest thing to have ever stomped across the land.

When Humboldt came to America in 1804, he was feted with a feast beneath the skeleton, which Peale had installed in his museum in Philadelphia. Humboldt joined Jefferson in “seeing America as a place that is rich in natural wonders, even if it’s short on man-made wonders,” Harvey says. “He and Jefferson basically accelerate[d] us down the path of believing that our national identity is grounded in what’s already here.”

Harvey wants the mastodon in her exhibit “to make the point that it’s natural history and natural monuments that bond Humboldt with the United States.” Displaying the mastodon, she hopes, will evoke the feeling that swelled in the early 19th century, when Peale put the skeleton on view. It was a cocktail of paleontology, patriotism, and peacocking—a way of saying, “‘Hey, you know, we’re not some brand-new republic that has no history and no credibility and maybe no future,’” Harvey says. “It was really a matter of saying, ‘If robust creatures like this once walked the earth of North America, think of where our future is going to lead us.’”

As she began to plan the exhibit, Harvey had good reason to think that she might not be able to bring the bones home: They hadn’t left Germany since they’d arrived there in the mid-1800s, after Peale’s museum went belly up; France needed to offload them during the tumultuous 1848 revolution; and the British Museum passed completely.

In the winter of 2019, Harvey visited Germany and met the mastodon and its custodians at the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt. To her surprise, they were game. Oliver Sandrock, a curator and paleontologist in the museum’s department of Earth and life history, appreciated Harvey’s plan to frame the prehistoric creature as key to the fledgling country’s self-conception and what it had to offer. “I said, ‘Yes, that’s a good story,’” Sandrock says. “So we’ll do it.”

But there were still slews of logistics to think through. Long before curators load a loaned object onto a plane, they’ve got to puzzle out each step of the process to ensure that things will go smoothly on the other side. Is the thing stable enough to transport? Will it make it into the building? Moving crates can be “like turning a semi,” Harvey says, and there’s not always a lot of wiggle room for maneuvering in museum hallways. Harvey had to figure out whether she could wrangle the mastodon on and off of freight elevators and shepherd it into the third-floor gallery where she plans to install it. (And, for that matter, whether the floor can withstand the weight.)

Sometimes curators get creative: Once, to ease a large painting into the building, Harvey’s team enlisted a crane to hoist it in through a glass-free window, then replaced the panes after the artwork had been safely settled inside. In the case of the mastodon, Harvey realized it would be a close call. When the skeleton arrives at the museum this winter, Harvey says, the tallest of the crates will just barely make it out of the freight elevator that opens into the exhibition space. At most, it will have just two inches of headroom.

“The elevator is plenty big, but the exit doors are smaller,” Harvey adds. When the building was constructed, “No one expected to be moving a mastodon.”

Once everyone was convinced that the plan wouldn’t fall to pieces, the German team began preparing the mastodon for its journey. First they cleaved the skeleton into five segments based on existing armature running through the skeleton. The skull is one unit. The second and third are made up of the right and left forelimbs. The fourth—the largest of them all—is the barrel-shaped rib cage. And the pelvis and hind limbs comprise the last section.

Then they splayed out the bones—and the wooden additions that take the place of missing pieces, and make the skeleton look complete—for several weeks of cleaning. An alcohol-based cleaner and gentle blasts of dry ice will remove the old, yellowing varnish without compromising the bones beneath, and allow researchers to parse the skeleton from painted wood. (Topped with centuries’ worth of accumulated gunk, it’s hard to tell the difference.) Sandrock is noodling over ways to help viewers distinguish between bone and wood, now that he and his team have the chance to give the creature a thorough refurbishing. He thinks it’s a distinction worth noting.

“Paleontology has nothing to do with completeness,” he says. “It’s bone fragments, tooth fragments, skull fragments. In my opinion, it’s important that visitors see the fragmentary nature of fossils.”

The museum will also take the opportunity to correct some previous interpretive mistakes. For one thing, says Sandrock, the creature’s skull and tusks aren’t quite right: The top of the skull was never found, and the current iteration, capped with gypsum, is too pointy—more like a woolly mammoth’s. The original tusks were never retrieved, either, and the newspaper-stuffed stand-ins are too swoopy—again, more suitable for a mammoth than a mastodon.

The skull will be shaved down with a saw, and then remade with molded epoxy resin to the specs the team has found in high-resolution 3D scans of complete mastodon skulls online. New resin tusks will be straighter, and the existing ones will go to the museum’s pedagogy department, where educators will refer to them as proof that “a museum is a living thing,” Sandrock says, grappling with its past and growing from it.

Once cleaning and tinkering are complete, and a blacksmith has built a high-grade steel structure that will connect the segments with joints that will make it simple to disassemble and reassemble, each will be tucked into its own custom-built wooden crate. They’ll likely be packed with carved foam that snugly cradles the shapes (similar to how you might ship expensive wine). No one will “close any box until they’re 100-percent sure that not a single phalange is moving” en route, Sandrock says.

The crates and their contents are designed to insulate the object inside from vibrations and drastic temperature fluctuations. Unlike most museum galleries, the belly of a plane isn’t climate controlled. “It’s going to get cold up there,” Harvey says. “Crates are engineered to make sure that temperature change is not going to damage the work.’

Still, transporting valuable objects can be a nail-biting process, whether the object in question is high-profile or flying incognito. As Frederic Church’s painting The Icebergs made its way to Dallas, after selling at Sotheby’s in 1979 and smashing auction records for American paintings, it was packed in an unassuming crate marked “household goods.” Its importance was so thoroughly disguised that the crate wound up being bumped to a later flight, and spent a day lounging on the airport tarmac. “It’s like, ‘Whoa. Oh, my God. Please, no,” Harvey says. “I think everybody was a little bit horrified, but fortunately, the painting was not damaged.” Other high-profile objects have been ushered through the streets with a convoy of museum staff and police officers.

This mastodon won’t get a police escort, but it will be accompanied by a few museum chaperones, who will ride with it by truck from Darmstadt to Frankfurt, then by plane to JFK, in New York, and then pile into a truck again to drive to Washington, D.C., Sandrock says. They’ll use cranes to hoist the the heaviest parts into place in the gallery. In all, Sandrock expects that assembly will be about a day’s work, with four crew members pitching in.

Jefferson tried to make the case that mastodons were both a precursor and a promise—because America had once been home to these huge creatures, the country’s future was bright. But fossils aren’t prognosticators: They’ve been swaddled in layers of dirt and rock longer than any politician has been alive, and stay there with little mind to anything going on above them. Harvey points out that the mastodon skeleton has been in Europe for much longer than it was ever displayed in the United States.

How does a prehistoric fossil become American, and when does it become something else? Its legacy, now, is as a well-traveled creature that puddle-jumped the pond and earned fans on either side. But for a few months, in a rotunda on the third floor of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, one of the country’s most dearly departed tusked residents will be back on its old trundling grounds.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook