The Haphazard History of the U.S. Open’s Best and Worst Venues, Soon to Be Rubble

They date to the 1964 World’s Fair.

Louis Armstrong Stadium, with CitiField to the left and, in the distance, the Whitestone Bridge. (Photo: Kai Brinker/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Fans attending the U.S. Open for the first time always find it curious that the championship’s second biggest venue is named after virtuoso American trumpeter Louis B. Armstrong. Did Armstrong have a secret tennis past? Or was it just a relic of a different age, when we named things after actual humans and didn’t sell rights to the highest corporate bidder?

The answer is even stranger: Louis B. Armstrong Stadium, in fact, began life as one of the earliest examples of a venue that was named for a sponsoring company.

The stadium, set to be demolished in the coming months to make way for a bigger, more modern venue carrying the same name, is today, an oddity, even on the campus of the U.S.T.A.’s Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, a haphazardly built maze of dozens of courts in Flushing Meadows, Queens.

Armstrong’s seats are cramped affairs, its court a large, hot rectangle, while the stands, with no protection from the sun, might get even hotter. It is not, in short, a fan or player favorite.

“If it’s not completely full it looks half empty,” the Serbian Janko Tipsarevic said Tuesday after beating the 32nd-seeded American Sam Querrey on Armstrong. “It’s not fair.”

Shoved up against it, however, to the east, is the Grandstand, a smaller affair (6,000 capacity, versus Armstrong’s 10,000-plus), with an appropriately smaller court, that is widely beloved. (“Grandstand. The Grandstand,” Tipsarevic repeated Tuesday after being asked his favorite court on the grounds, an opinion shared by many players.)

The Grandstand, cut into the side of Louis Armstrong, during a match in 2015, with onlookers at Armstrong perched above. (Photo: Steven Pisano/CC BY 2.0)

Yet, sometime after the U.S. Open concludes on September, both will be rubble. That will end a legacy at the tennis center that dates back over five decades, while also, officially, turning a page on the sport’s rich Queens past.

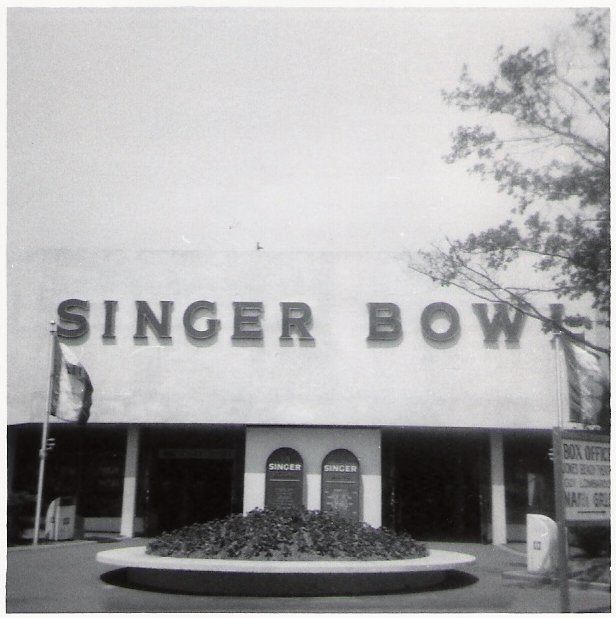

Both Armstrong and the Grandstand began life in the early 1960s as the Singer Bowl, built by the Singer Sewing Company. The company fashioned the rectangular, 18,000-capacity venue in anticipation of the 1964 World’s Fair, donating the venue to the fair, after which it was supposed to be demolished. But it lived on, giving Singer some surprising returns on its initial one-off investment.

According to the New York Times, Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Ella Fitzgerald, and The Doors played there in the late ’60s. The Mets also celebrated their 1968 world title there, in addition to several other large events, like a Ukrainian cardinal celebrating Mass (strangely, the morning after the Doors concert) on Aug. 3, 1968.

In 1973, a few years before it began hosting the U.S. Open, the venue was christened the Louis B. Armstrong Memorial Stadium, after the renowned bandleader, a Corona, Queens native, who had died in 1971. When the USTA left the Forest Hills Stadium for Armstrong in 1978, the name—grandfathered in at this point—stuck. The stadium was rebuilt for tennis, and, with some room to spare, the Grandstand tacked on too.

Up until 1997, Armstrong was the tennis center’s premier court, hosting each year’s finals. But Arthur Ashe Stadium—the largest purpose-built tennis stadium in the world—was completed that year just a hard forehand away, taking Armstrong’s mojo, while also, perhaps, dooming Armstrong and the Grandstand to their fates.

”The new stadium is beautiful; it seems very well put together versus the old place,” Pete Sampras said shortly after Ashe’s opening, before almost immediately getting nostalgic. ”But I kind of miss the old stadium because it’s kind of where I made my mark in ‘90.”

The facade of the Singer Bowl. (Photo: Doug Coldwell/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The demolition of Armstrong is part of an ambitious, $550 million campaign the USTA has set upon to modernize its grounds in Queens. That includes a now-functioning roof over Ashe, as well as a new Grandstand, which opened this year to (mostly) positive reviews. And then there is the new Armstrong, set to be built on the site of the old one and scheduled to open in 2018.

“I love that court,” the 29th-ranked Sam Querrey said Tuesday of the old Armstrong, when asked if he’d miss it. “It’s one of my favorites. Hopefully I’ll get a chance to play on the new one, whenever it’s done.”

But all of that work, however much better for the USTA’s bottom line, will also mean that the last vestige of the grounds where John McEnroe, Chris Evert, Steffi Graf, and Pete Sampras were all crowned champs will be gone.

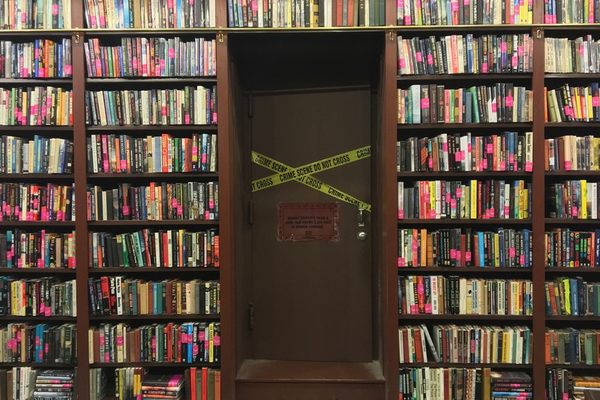

The old Grandstand on Tuesday night. (Photo: Erik Shilling)

Or, maybe, just maybe, there’s some life yet. Last year’s Open was said to be the last for the old Grandstand, to become a practice court this year in anticipation of its removal. But a strange thing happened this week: Court 10 was deemed unplayable, and officials opted to open the old Grandstand for competitive matches for one last swan song.

On Tuesday night, Nick Kyrgios, the controversial, if effortlessly watchable and charismatic young Australian player, faced off there against Aljaž Bedene, a Slovenian-turned-British player ranked 77th in the world, in one of the last matches of the day.

The lights were on, but the billboards were blank, and the stadium was less-than-half empty. The crowd, though, was in good spirits, including a hearty contingent cheering on Kyrgios, who was battling a hip injury. It felt more than full.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook