The Ingenious Plan to Win World War II With Iceberg Airbases

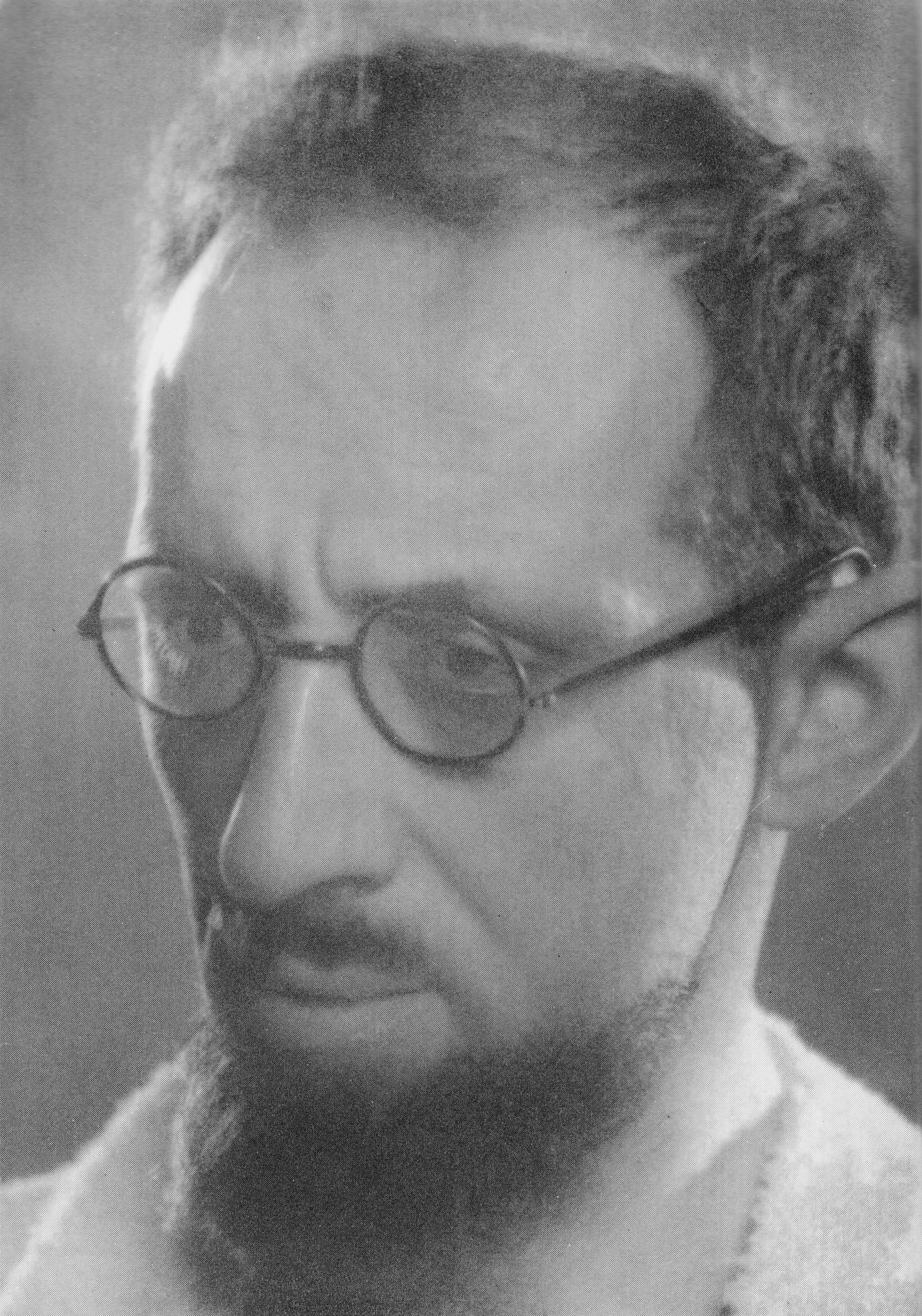

A portrait of Geoffrey Pyke from the 1930s (Photo: Courtesy of the Geoffrey Pyke Archive)

In The Ingenious Mr. Pyke, Henry Hemming tells the story of Geoffrey Pyke, a talented British polymath who escaped a German prison camp in WWI, sparked a revolution in early education, tried to intervene in the Spanish civil war, and just might have been a Soviet spy. By the time World War II was in full swing, even as MI5 kept a close eye on him, Pyke was employed by the British War Office—which had sent him to America, to work with U.S. military’s Office of Science and Research Development. Pyke was constantly coming up with unusual solutions to huge problems—the idea that took him to America had to do with mounting soldiers on snowmobiles—and in the excerpt below, Pyke comes up with yet another quirky and possibly brilliant idea for ending the war. What they needed, he argued, was icebergs.

During the summer of 1942, in the tight and swampy heat of the American capital, Geoffrey Pyke came up with a plan to end the World War II by using ice. There were just two problems. One was that he might be sacked at any moment, the other was that too many people might hear the idea and laugh.

For many of us, laughter is an involuntary response to an idea or situation which challenges our understanding of how things should be while, at the same time, poses no threat. A joke is a “safe shock,” and throughout the history of invention some of the boldest and brightest ideas have been met with laughter. Pyke knew that he would be up against his “old enemy”—“the appearance of absurdity.” His only chance of having this proposal taken seriously was to win over a man like Lord Louis Mountbatten, Chief of Combined Operations, who understood that new ideas could be both useful and funny.

In the weeks after being ordered back to London, Pyke disappeared. He did not return to Britain, and in OSRD a rumor circulated about him being holed up in a New York hotel, hard at work on some mad new scheme. Another story was that he had checked himself into a “mental institute.”

Instead he began to shoot up and down the Eastern Seaboard like a man who had lost something. He ate solitary meals in hotels, exchanged telegrams with an Austrian polymer scientist living in America and tracked down obscure texts on the properties of ice. He made at least one trip to Lake Louise in Canada and on two separate occasions went to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, complaining of chronic exhaustion.

On his second visit to the Mayo Clinic, in September, Pyke stayed for several weeks, and as he slid between the extremes of complete exhaustion and a blissed-out chemically induced high, he finished his proposal. Given the need for secrecy, he had asked William Stephenson of British Security Coordination to supply a trusted secretary, who now took his finished proposal to New York where it was sent to London by diplomatic bag. On 24 September an enormous, book-length dossier arrived on Mountbatten’s desk from the Mayo Clinic. “It may be gold: it may only glitter,” read the note stapled to the cover. “I have been hammering at it too long, and am blinded.”

Mountbatten was busy and might have put this vast memorandum to one side had it not been for its epigraph, taken from one of his beloved G.K. Chesterton “Father Brown” stories.

Father Brown laid down his cigar and said carefully: “It isn’t that they can’t see the solution. It is that they can’t see the problem.”

This intrigued Mountbatten. Perhaps more than any other pair of sentences it seemed to embody one strand of his intellectual outlook. He turned the page and began to read.

Work on the aircraft carrier at Lake Louise in Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of National Research Council Canada Archives)

How to Win the Battle of the Atlantic with Ice

Churchill would describe the Battle of the Atlantic as “the dominating factor all through the war. Never for one moment could we forget that everything happening elsewhere, on land, at sea or in the air depended ultimately on its outcome.” Pyke’s proposal described how the Allies could win it.

He began with a series of stark assertions: Britain’s ability to wage war depended on the millions of tons of vital supplies it received across the Atlantic; most of these were transported using unarmed ships manned by civilians; there were not enough Allied warships to protect them all; over parts of the ocean there was no air cover; Allied ships were being sunk in the Atlantic faster than they could be replaced.

Few military strategists would argue with any of this. June 1942 had been the worst month yet in the Battle of the Atlantic, in which a staggering 652,487 tons of Allied shipping had been sunk, most of it by submarines marauding in a hitherto anonymous strip of ocean now known as “U-Boat Alley.” It was impossible to win the war without victory in the Battle of the Atlantic. No less important was the ability to mount attacks on enemy supply lines. Allied efforts fell short on both due to a lack of air cover. In each of the major naval exchanges of the war—whether it was the attack at Pearl Harbor or the sinkings of the Prince of Wales, the Repulse or the Bismarck—aircraft had played the decisive role. Only now was it becoming clear that control of the seas depended upon mastery of the air. So how to achieve this over the Atlantic?

In an imaginary world Churchill might have waved a magic wand to conjure a fleet of new aircraft carriers, each vessel magically immune to torpedoes, comfortable in rough seas, requiring very little steel to build and capable of accommodating long-range bombers and fighters. This was fantasy, of course. There seemed to be no realistic solution to these strategic problems other than building up Allied military strength using existing weaponry until victory was assured by weight of numbers. Pyke proposed something else. He had found a way to turn fantasy into reality.

His starting point was a dog-eared 1924 copy of the National Geographic Magazine which contained an account by Captain Zeusler of the north Atlantic Ice Patrol of what had happened when his men fired six-pound shells at an iceberg. Rather than shattering into icy smithereens, as you might expect, given that ice is brittle, these bergs absorbed the shells. None penetrated more than a few inches while some failed to explode. Zeusler had been bemused. Pyke was intrigued. The article also touched on the history of collisions with icebergs, stressing that the sinking of the Titanic was not an isolated incident but one of hundreds of encounters between boat and berg in which the vessel would always come off second-best. Pyke asked himself a silly-sounding question: was it possible to harness the colossal strength of icebergs to the Allied war effort?

At this point, Pyke had a fortuitous conversation with Professor Herman Mark, a charming Austrian scientist in his late forties who would later become known as one of the pioneers of polymer science. … During their conversation Mark showered Pyke with information about ice, including the fact that it melts at a much slower rate when insulated. Were you to place a cube of ice some 300 feet wide in water heated up to 52º F., it would melt in less than a week. Surround that block with a wall of wood just one foot thick and it would lose no more than 0.9 per cent of its volume in 100 days.

This appeared to change everything. Pyke pictured an Alaskan iceberg insulated by wood and hollowed out to store military materiel. Knowing that planes had performed emergency landings on the tops of icebergs in the past, perhaps the cap of the berg could be leveled off to form a runway? Effectively this would create a floating airfield. Tow one of these into U-Boat Alley, in the mid- Atlantic, and aircraft based on it could lay waste to nearby enemy submarines. Better still, it could be done at a fraction of the cost of building a new aircraft carrier from steel. Given that ice was so cheap, why not build an archipelago of these customized floating islands?

“The war can be won either by having ten of everything to the enemy’s one (including the ships to carry it),” he wrote, “OR by the deliberate exploitation of the super-obvious and the fantastic.” Pyke had combined three “super-obvious” ideas: icebergs are hard to destroy; ice melts slowly when insulated; ice is cheap.

It is also brittle, which was why a customised iceberg along these lines could never work. It lacked the necessary crush resistance to withstand powerful mid-Atlantic swells and would break up after reaching U-Boat Alley. The resistance of a material that could cope, such as high-grade reinforced concrete, was 4,000 pounds per square inch (psi). Ice, at best, had a resistance of 1,300 psi, making it significantly weaker than even low-grade reinforced concrete.

This would have been a good moment to abandon this train of thought. Many of us, at this point, might have done so. Pyke had checked his fantasy against reality and found it to be unworkable. But he did not let go. He saw this as the kind of setback one should expect when tackling a problem of this magnitude. Instead he took a step back and tried to unbutton his mind. He had to distance himself from every assumption that he had ever held about ice, to banish from his imagination the traditional uses of ice and to think of this material instead as if he were a scientist who had discovered it for the first time.

Lake Louise. (Photo: Courtesy of National Research Council Canada Archives)

Lake Louise. (Photo: Courtesy of National Research Council Canada Archives)

What had happened to most other new materials following their initial discovery? Iron had been alloyed with other materials to produce steel; wire had been added to concrete to make reinforced concrete; raw copper, as he knew from his days as a copper investor, had been smelted and refined. In other words, each of these new materials had been artificially strengthened. Why not do the same to ice?

Earlier that summer Pyke had picked up a copy of the forbiddingly titled Refrigeration Data Book of the American Society of Refrigeration Engineers and had read that “frozen sand is harder than many kinds of rock.” The implications were fascinating. It seemed to suggest that you could strengthen ice by adding materials such as sand to the water before it is frozen.

At this point Pyke had a rare stroke of luck. He asked Professor Mark to carry out several experiments into reinforcing ice, only for this Austrian scientist to say that he had already begun.

“I told him that when I worked in a pulp and paper mill in Canada, we found that the addition of a few per cent of wood pulp greatly increased the strength of a layer of ice.” Not only was Pyke right about strengthening ice but he was speaking to perhaps the only man in the world to have already begun experiments along these lines.

Breathless at the thought of what might be just around the corner, Pyke asked Mark to conduct fresh investigations into the properties of ice made from water to which sawdust or cork had been added. The results were extraordinary. This reinforced ice was not only stronger than pure ice but the wood pulp formed a soggy protective layer which slowed the speed at which it melted. Two birds had been killed with one stone. Mark’s team was now producing reinforced ice which melted slowly and had a crushing resistance of 3,000 psi—a greater tensile strength than many varieties of reinforced concrete. A square column of this strengthened ice, measuring just one inch across, could support a medium-sized car.

These were only the initial results. In time Mark’s team was bound to find more fecund combinations of water and wood-pulp. “The possible repercussions of having a material of this quality that can be made in any desired shape, uniform and monolithically AND which floats, are obvious.”

Just before Mountbatten ordered him back to London, Pyke’s iceberg scheme underwent its final evolutionary leap. Rather than customize a natural berg, Pyke proposed to build an artificial one using reinforced ice. Just as a refrigerating ship is kept cool by a series of ducts webbed out over its hull this man-made berg would contain ducts capable of keeping the temperature of the ice low enough for it to sail through tropical waters.

The document he sent to Mountbatten seven weeks later was summarized by its title: Mammoth Unsinkable Vessel with Functions of a Floating Airfield. This “berg-ship” made out of reinforced ice would be cheap to build and, on account of its gargantuan size, would be capable of accommodating even modern fighters and bombers. It would measure at least 2,000 feet from bow to stern, making it twice as long as the ocean liner Queen Mary and twice as wide; this would be the largest vessel ever made by man. What was more, it would be unsinkable.

Water weighs eight times less than steel but is heavier than ice. A berg-ship could not be sunk. To destroy it, an attacker would need to break the vessel up into thousands of tiny pieces, all of which would float, and do this before the initial holes in the hull could be patched up. Here was another startling claim: “A battleship, when hit, has to go into port for repair. There is no such need for the berg-ship. The damage done by projectiles can be repaired at sea and in a very short time. All damage will be made good by filling the hole with about five-sixths crushed ice and water replacing the refrigerating pipes (made of cardboard) and refreezing.”

The berg-ship, in theory at least, was an astounding improvement on the modern aircraft carrier. Each one would be cheap, unsinkable, capable of carrying heavy bombers and equipped with one of the most powerful secret weapons in any war: surprise. Until then, most major breakthroughs in naval design had occurred in peacetime, and as a result of this few sides had ever gone to war with a telling technological advantage over the other. The berg-ship was different in that it had been conceived during a war. Weapons designed to sink ships of steel would have little or no impact. Magnetic mines would drift harmlessly past; torpedoes would perforate the ship without sinking it. “Its adoption by one side will give advantages of surprise that have, I believe, never accompanied the introduction of a new strategic material.”

Lacing the proposal together were broader ideas about deception, the need to take ground without holding it and the importance of winning civilian hearts and minds. Some of this extraneous material has since been dismissed as science fiction, which it was, in the purest sense. But to understand Pyke is to realize that every idea he had was science fiction—science in the fictional stage of its development. This is the passage through which every scientific idea must travel before it can be subjected to rigorous experimentation. What set this proposal apart was the extent to which Pyke had allowed his imagination to race beyond the point at which most scientists would stop. This is why some of it felt outlandish or silly. “One way to beat the Germans is precisely by being—not merely funny—but funny, and as thorough as the Germans are. Do you think the men who conceived and built the Trojan horse were stiff and solemn men?” Again he was pointing Mountbatten towards something more than cunning and intelligence or what the Ancient Greeks called metis. His emphasis was on laughter, the gateway to deception, which destroys German morale. The goal should be not just “to beat them but to make fools of them in beating them.”

For all its flights of fancy Pyke’s scheme contained a brilliant military innovation. It proposed an unsinkable aircraft carrier made out of a cheap new material that could be produced quickly. Yet his paper was merely a starting point, “a catalyst of the ideas of other people. No idea is a good one which does not breed its own successors.” It was up to Mountbatten to grasp its potential. If he did and was able to press it upon Churchill with characteristic gusto then the scheme might survive its infancy.

Pyke’s only chance of beating his old enemy, the appearance of absurdity, was by winning over Mountbatten. He had become both patron and muse, which was why Pyke chose “Habakkuk” as a cover-name for this proposal (misspelt by his American secretary as “Habbakuk,” the spelling that stuck).

Habakkuk was the Old Testament prophet who had warned: “Be utterly amazed, for I am going to do something in your days that you would not believe, even if you were told.” There is also a Donatello sculpture of the same name, a hollow-eyed Habakkuk who seems to stagger under the weight of his prophecy, and who bears an uncanny resemblance to Pyke. But the intended reference was to what Pyke imagined to be Voltaire’s line on Habakkuk: “Il était capable de tout.” So was Mountbatten. From a hospital bed in the Mayo Clinic, his mood mediated by powerful drugs, Pyke began to wait for a response.

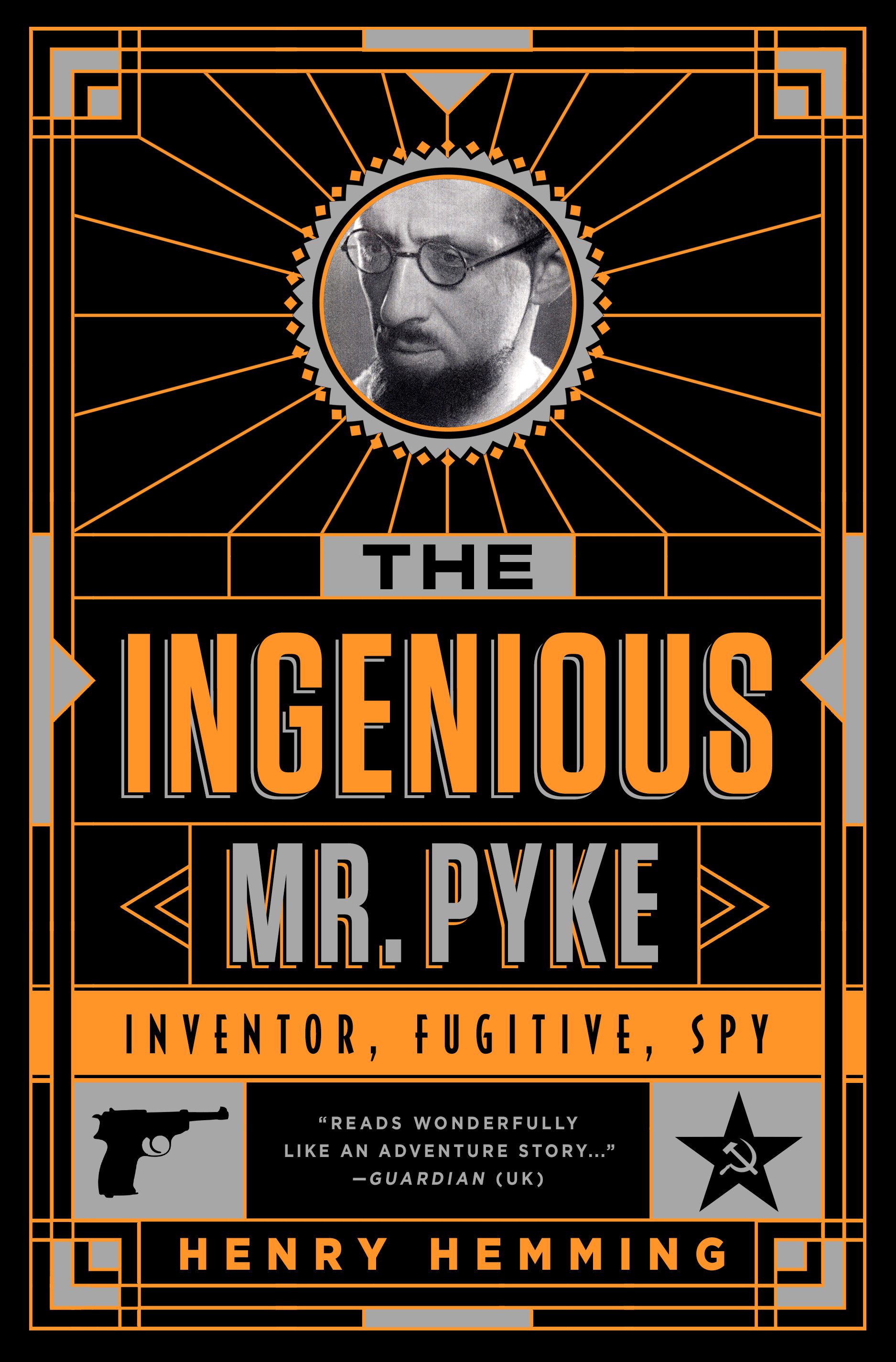

(Photo: Courtesy Public Affairs Books)

(Photo: Courtesy Public Affairs Books)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook