The Self-Sacrificing Japanese Pilgrims Who Chose to be Swallowed by the Sea

For 1,000 years, Buddhists in Japan sealed themselves into boats and let the waves carry them.

Two Buddha statues in Japan, showing Bodhisattva Seshi (left) and Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (right). (Photo: Nelo Hotsuma/CC BY 2.0)

Sometime around the year 1000, a young man in Japan named Sanuki no Sanmi became worried about the state of his soul. He wanted to make sure that his next reincarnation was a good one. So he set about making preparations. His first thought was that he should burn himself alive. The gift of his body was a sure path to an unsullied rebirth.

But then, Sanuki began to reconsider. At that time, one’s mental state at the moment of death was thought to have a profound influence on the nature of one’s next life. Unless one maintained perfect concentration until the moment of death, a positive reincarnation could not be assured. What if doubts entered his mind in his final agony? Then Sanuki had a better idea. There was one place where he could enter a Pure Land in his present body, without having to endure death: Mount Potalaka.

Sanuki knew that Mount Potalaka was located somewhere in the sea far to the south of Japan. So he made his way to Tosa Province and acquired a small ship. He asked a sailor to let him know when a wind from the north would blow without letting up. When the day came, he boarded his boat and set out for the open ocean. A crowd gathered to watch him depart. As he vanished over the horizon, his wife and children watched from shore, weeping. All who saw the strength of his resolve were sure he must have reached his destination. He was never seen again.

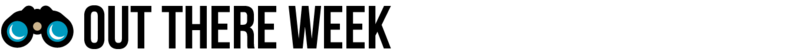

Kumano Nachi Mandala, showing a pilgrimage in Japan, from 16th or early 17th century. The boat at the bottom shows Fudaraku Tokai. (Photo: Public Domain)

Sanuki’s story is one of the first mentions of a Buddhist ritual particular to Japan called Fudaraku tokai. The name means “crossing the sea to Fudaraku,” the Japanese name for Potalaka. Those who undertook the journey set out in small boats from the southern coast of western Japan. Usually they were sealed inside their ship, which was boarded-up like a coffin. Sometimes they leapt into the ocean or pulled a wooden plug from the hull when they were far enough out to sea. Either way, the outcome was almost certain death.

Fudaraku, or Potalaka, was the mythical dwelling place of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (the Potala Palace, the seat of the Dalai Lama in Tibet, gets its name from the same source). It is a paradise, one of several “Pure Lands” in the Buddhist tradition. Potalaka was thought to be an immensely tall mountain, surrounded on all sides by rocky valleys and dangerous cliffs. From one direction it was said to look like dragons sleeping; from another, like tigers crouching. Lush forests grew at its base.

It was a mythical place, but like Avalon or Atlantis, it was also of this world. Sanskrit sources said it was located in southern India. The great Chinese traveler Xuanzang claimed it was east of Malaya. In Japan, it was generally believed to be an island somewhere far out in the southern seas.

Pothigai Hills in Tamil Nadu, India. Some scholars believe that this is Mount Potalaka. (Photo: Sdsenthilkumar/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The ritual of Fudaraku tokai was carried out only rarely. Some 57 instances are recorded, but it was performed in nearly the same way over a span of almost a thousand years. Some performed the rite to escape embarrassment at court. While out hunting with his lord, Shimokobe Rokuro missed a deer with his arrow. Disgraced, he fled to the Kumano Mountains where he became a monk, reciting the Lotus Sutra day and night. After some years, he descended to the sea and had himself sealed in a boat and cast off in the direction of Fudaraku.

Others set out for the southern sea after suffering defeat in battle. In 1184, at the end of the Genpei War, a man named Taira no Koremori, having escaped the final defeat of his clan, decided to make a pilgrimage to the Pure Land. The Heike Monogatari, the great military epic of 12th century Japan, describes how he boarded a small boat and rowed out into the open ocean.

Once there, “he put away distracting thoughts immediately, intoned the Amida’s name a hundred times in a loud voice, and entered the sea with ‘Namu!’ on his lips,” entrusting himself fully to the Buddha’s compassion.

A depiction of the Battles of Yashima and Ichinotani, part of the Genpei War, from The Tale of Heike, late 16th century. (Photo: Christie’s/Public Domain)

Most often though, travelers to Fudaraku undertook the voyage in the hope of achieving salvation. Every element of the voyage was imbued with ritual meaning. The boat in which the pilgrim was sealed was laid out like a funeral ground. Their body rested inside a square fence made out of 49 staves, to represent the required days of mourning for the departed, and was pierced by four gates, each corresponding to a stage in the Buddha’s life. The tokaisha, or pilgrim, was dressed in robes which bore an image of the nine levels of the Pure Land. The mast and rudder of his boat were made from fragrant woods, and its sails were inscribed with Sanskrit characters and verses from the Lotus Sutra.

Although the journey to the Pure Land was a solitary one, the pilgrim usually did not set out alone. Crowds of mourners gathered on shore to see them off. His boat was towed by two others, one carrying monks and priests, the other, a group of mountain ascetics. The two boats followed the pilgrim out into the middle of Nachi Bay. When they reached Kokinshima, the Rope-Cutting Island, they severed the connection between them and left the tokaisha’s sailboat free to drift toward the southern paradise. At this point, the pilgrims usually flung themselves into the sea.

Fudarakusan-ji Temple in Japan, named after Mount Potalaka. (Photo: 663highland/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Portuguese Jesuit missionary Caspar Vilela, who witnessed a performance of the rite in 1562, wrote of his surprise at how “joyfully” they did so, while Luis Frois, another missionary, wrote of his own disgust at seeing the ritual performed:

“Although the crowd appeared mournful and sobbing, they knew in their hearts that they [the tokaisha] were becoming sanctified and wished that they too could be crossing the boundary to beatitude…When the boat had reached an adequate distance from the shore, they each threw themselves into the deep ocean–or more accurately, into the depths of hell.”

The tokaishi didn’t always throw themselves into the ocean. Sometimes, they waited until they were far out to sea and pulled a pre-drilled plug in the hull of their boat. Those who stayed inside their sealed cabin for the duration, outfitted with only than a lamp and a 30 days’ supply of food. When this ran out, they presumably died of thirst or starvation.

The detail of the boat. (Photo: Public Domain)

Occasionally, the pilgrims even survived the voyage. When a monk named Nisshu Shonin set out for the Pure Land in the 16th century, a gale took him off course and he was washed ashore in the Ryukyu Islands. Upon arriving, he decided that he had actually reached his destination, spent the rest of his days in meditation, “purifying himself of defilement and floating the boat of wisdom.”

The journey to Fudaraku was meant to be a way of securing eternal peace. But the ritual itself wasn’t always so peaceful. A story in a 13th-century collection of tales describes a priest who decided to drown himself in order to be reborn in paradise. On the appointed day, hundreds gathered to watch him depart. Once he hit the water, the priest had a change of heart and tried to scramble back to shore. The crowd turned on him immediately and began pelting him with stones until his head was split open and he sank back into the water.

An early 16th century depiction of Kannon. (Photo: Public Domain)

This isn’t the only case in which compulsion features as an element of the ritual. In Passage to Fudaraku, Japanese historical novelist Yasushi Inoue retells a 16th-century story of the abbot of a Buddhist temple who was forced by tradition to make the journey at the age of 61. Once he was underway, the abbot broke out of his boat and washed ashore on a nearby island. Other monks reached him and put him back on a boat and set him adrift once more. Before he was forced aboard, he wrote a poem of protest: “Should you seek Kannon/Believe not in Fudaraku/Should you seek Fudaraku/Believe not in the sea.”

So were the tokaishi voluntary seekers, or were they pushed? The practice of fudaraku tokai presents a conundrum: it involves people seeking a real place, in which they could live in their own bodies, but it was also a method of ritual suicide, in which the sins of the community were placed on the head of a sacrificial volunteer. The tokaishi were at once pilgrims, scapegoats, explorers, and self-sacrificers.

Inoue’s story is alive to these contradictions. One of the doomed abbot’s predecessors goes to Fudaraku full of foreboding, certain that he is going to die on the way. Another departs joyfully, certain that he will soon get there. To this monk, Fudaraku is certainly real. It is a place of untold beauty, where people never age, the plants never wither and the skies are full of great flocks of vermillion birds. He can already see it, glinting on the horizon: a green tableland, level and high, surrounded by an infinite expanse of calm.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook