These Magic Bags Turn Pee to Goo And Make Poop Portable

Welcome to the frontier of human waste management.

The Restop 2. (Photo: Restop)

There are places in the world where human poop just does not decompose that quickly. Conveniently, these are places humans do not often go—deserts, high alpine planes, the steep-sided gorges of fast-running rivers. When these areas do become popular with hikers, climbers and other explorers, though, poop can become a problem.

Welcome to the world of disposable human waste bags.

New policies. (Photo: wetwebwork/crop/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Combining the principles of kitty litter and plastic bag-based poop-scooping (a skill of urban dog owners everywhere), these bags rely on trade-secret combinations of gelling agents, enzymes and deodorizers to sequester human waste into a manageable package.

The gelling agents almost instantly transform urine into goo—disposable diapers use the same sort of substances. The enzymes break down solid waste, enough that the bags can be disposed of in regular old garbage cans. The nice-smelling compounds have an obvious function.

These bags generally cost about two or three dollars each and can be purchased in conjunction with infrastructure, like a simple commode or privacy tent, to more closely replicate the experience of using a toilet. It’s like having your own personal Porta-Potty.

A trail on Mt. Whitney, where it’s required that campers pack out poop. (Photo: Justin.Johnsen/CC BY 3.0)

One of the leading brands of disposable solid and liquid waste bags is Restop, which is based in southern California, not far from San Diego. The Restop technology was first invented in mid-1990s, for utility workers who spent their days underground. The original inventor, Dan Young, had a small family business manufacturing items for utility companies, and he happened to be in a meeting with the Pacific Bell Telephone Company, when an emergency phone call came in. OSHA had shut down a site in Los Angeles, after a random inspection of a manhole had revealed a terrible stench of urine.

It was too much trouble for Pac Bell workers to climb out and find a bathroom, so they were just peeing underground, a violation of health and environmental standards. Young suggested that he start making the company a pee bag, and after he quickly created a rudimentary model, his contact put in an order for tens of thousands.

It turned out that there were other markets for human waste bags, too. They’re useful in emergency response situations, when normal sanitation systems aren’t functioning: in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, Restop was working double shifts to fill orders from FEMA. Survivalists sometimes stock them, too. They’re used by health aides and by people who just don’t want to use the public portable toilets at large events. Restop’s first fans in the military world were fighter pilots, who can’t exactly pull over to pee, but since the early 2000s, the U.S. military as a whole has been a significant consumer of human waste bags, used during operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

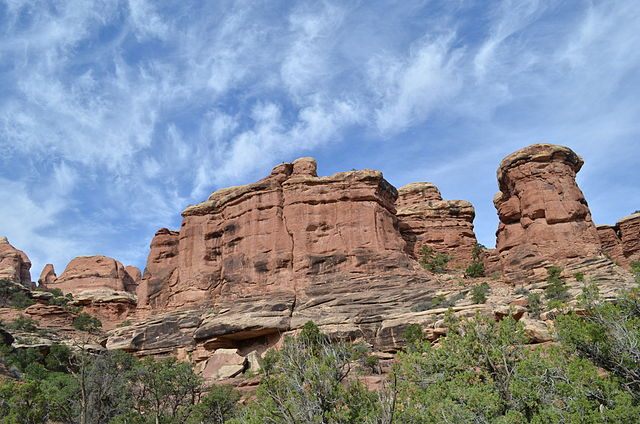

The Narrows’ Elephant Canyon, where people must carefully manage their waste. (Photo: RichieB_pics/CC BY 2.0)

At the same time, people hiking and climbing in remote places started recognizing that they needed to better manage their own poop. Traditionally, the best way to deal with human waste is to dig a cathole six to eight inches deep, a decent distance from trails and waterways, and bury it. But that doesn’t work everywhere.

“If you’re just backpacking the Pacific Northwest, things break down really fast,” says Kevin Seagraves, of the wilderness-focused nonprofit Leave No Trace. “In the desert, it takes a long time. If you bury it, it can get uncovered and washed into water systems.” Similarly, up on the highest mountains, microbes don’t do a good job of digesting human waste. And, on some adventures, like multi-day climbs up giant rock walls, there’s just no good place to go to the bathroom.

Hikers and climbers started by improvising their own waste systems. On mountains, “blue bags” became a go-to: this is basically the same system dog owners use, but involves two bags—a blue one to pick up the poop and a clear one to double bag it. Climbers invented what is colloquially known as “poop tubes”—basically just PVC piping with one end stoppered shut and the other end equipped with a removable, but secure cap.

Some solutions are more DIY. (Photo: Maria Ly/CC BY-SA 2.0)

About a decade ago, though, parks began pilot programs that required people to remove their waste from areas where poop had become a problem and providing bags to serve that purpose. (In addition to Restop’s products, a company called Clean Waste makes a product known as the Wag Bag that’s also popular with outdoors people.) Today, permits for popular backcountry trails up Mt. Whitney or through the Needles, in Utah, come with human waste bags, and rangers inspect backcountry parties to make sure they’re properly equipped.

Essentially, what this means is that, just as hikers have long packed out any trash they’ve created, now they sometimes have to pack out their poop, as well.

This puts a lot of pressure on these waste bags to perform as advertised: no one wants to carry around a stinking bag of shit for days, and some hikers have reported seeing bags of poop abandoned along trails. The Restop team takes the odor problem very seriously: the company’s product developer, Jeff Griffin, will put the worst-smelling materials he can find—rotting fish, cow manure—in the bags to see how they perform. (When he asked about the foulest scent he had experimented with, he said, “That would be chicken shit.”) That attention to detail does seem to be working: one Restop customer reported back to the company that he had left a used bag in his pack for three months and never noticed it was there.

To some extent, though, the requirement to carry waste bags in parks simply provides an additional incentive to plan hikes with an eye to optimizing the deposit of human waste.

“I’ve carried a Wag Bag in the backcountry, but never actually used one,” says Leave No Trace’s Seagraves. Usually there’s only a particular area where the bags area required, and outside that zone, digging a cathole will still suffice. “I might walk 14 miles so I don’t have to carry a bag of shit around,” says Seagraves. One of the major principles of Leave No Trace, after all, is to plan and prepare ahead.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook