The Artists Who Depicted War in a Whole New Way

These unorthodox images were used to drum up support for World War I.

In spring 1918, as hundreds of thousands of doughboys poured into Europe, one special group of eight American soldiers were brought together to provide an artistic take on the war. America’s first official “combat artists” roamed battlefields over the next year and produced a vast body of work—some 700 sketches and paintings—that captured the war experience for both the home front and the historical record.

The artists reported to the Committee on Public Information, an independent agency of the U.S. government, and simultaneously acted as historians and public relations officers. The images they produced and sent home were used to drum up support for American involvement in World War I—a war that President Woodrow Wilson had spent years pledging to keep the nation out of.

The American Expeditionary Force (AEF) Combat Artists, as they were known, had been professional magazine and newspaper illustrators, and were called into service at the rank of captain. They had total freedom of movement, and roamed the lines with special passes and dedicated cars. On the front lines they made sketches, which were then transformed into finished works back at a studio in safer territory. The art they produced was unlike any wartime imagery the public had seen before.

“Prior to that, most war art was heroic representations done far from the battlefield, long after the fact,” says Smithsonian chief curator Peter Jakab. “So this was the first time that you really had artists there in situ, and the idea was to create art in the moment, by the participants.”

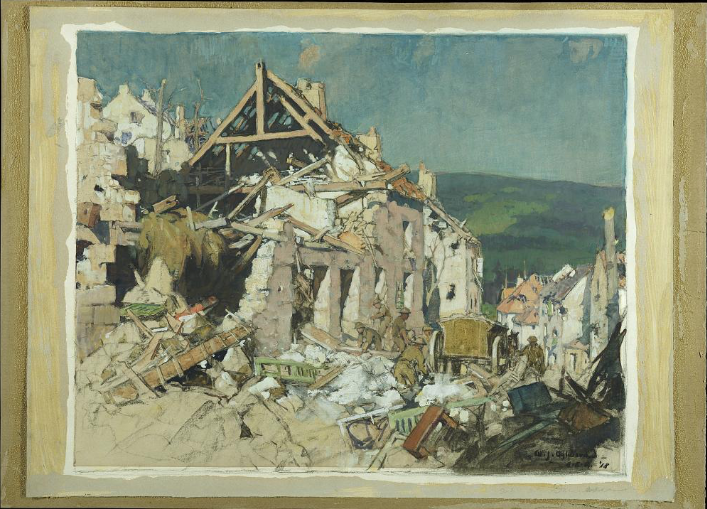

Both the style and subject matter of AEF combat art were departures from previous norms. Stylistically, the collection is rough and industrial—nothing like the delicate oil paintings used to depict previous conflicts. And the subject matter emphasizes the individual soldier—in a way that doesn’t come through in grand depictions of historical armies.

The collection reads, in many ways, like a visual diary, and it is easy to imagine one of the artists stumbling upon a memorable scene and stopping to sketch it in a notepad. Vast logistical systems, new technology, and the industrialized nature of war are reflected over and over in the collection. So, too, is destruction—both in human terms and as inflicted on the formerly picturesque French landscape.

After the Armistice of 11 November 1918 ended conflict on the Western Front, the U.S. Army’s official war art went to the Smithsonian Institution for a special exhibit, but it hadn’t been back on public display—until now. For the centenary of the American entrance into World War I, the collection has been brought out of storage, and is on view at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook