For Sale: A Titanic Survivor’s Light-Up Cane

Ella White’s battery-powered crutch guided her lifeboat to safety in 1912—and is now at the center of a family feud.

One dark night on the cold open ocean, Ella White steered 25 people to safety using only the light of her cane.

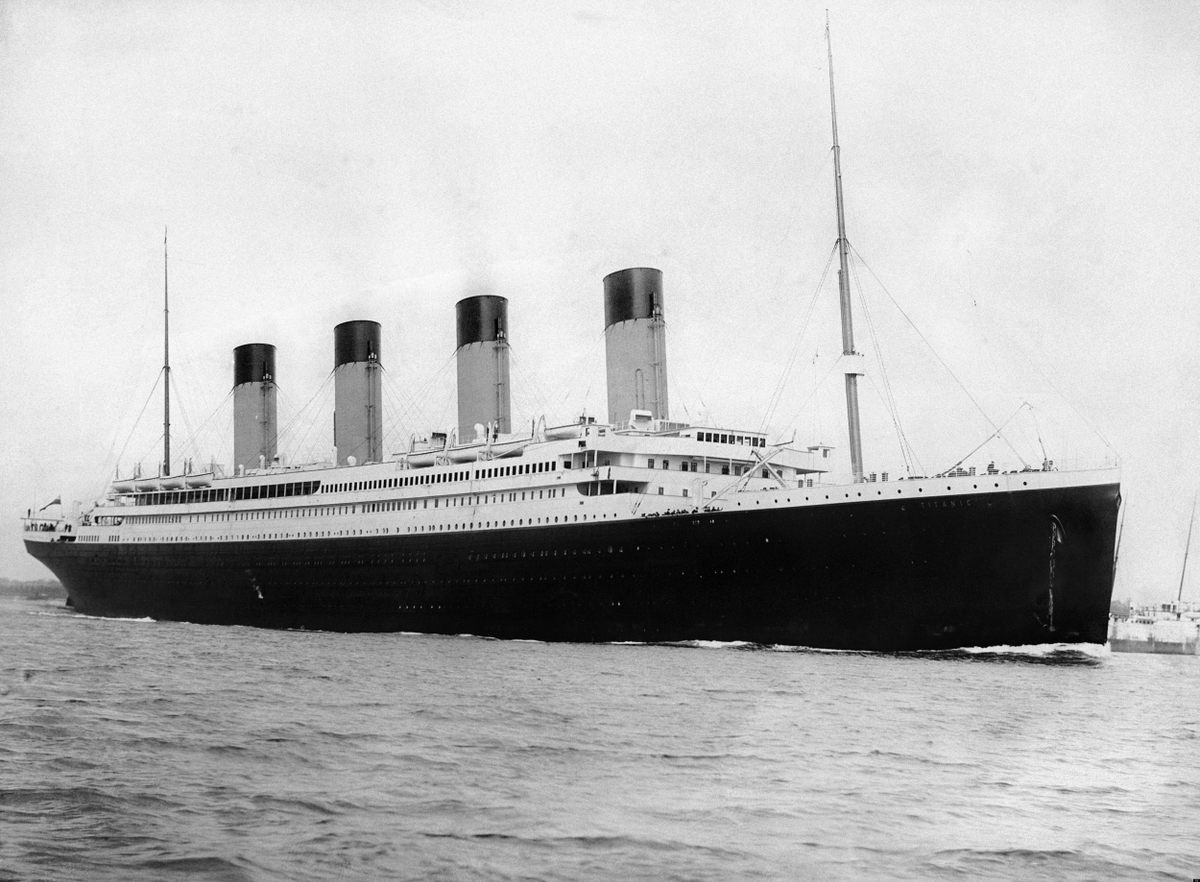

It was April 14, 1912, and as the Titanic began to fill with seawater, the wealthy widow paddled away on Lifeboat No. 8—the second boat to leave the sinking ship—along with 25 other passengers. White held her battery-operated cane aloft to illuminate the pitch-black, turning the lifeboat into a kind of floating lighthouse in the middle of the ocean. Eventually the group was rescued by a nearby ship called the Carpathia.

This week, the electric beacon that lit the frigid North Atlantic on that fateful night will be up for sale at Guernsey’s Auction. But it’s a contested auction, to say the least.

Like many other survivors, White, then 55, boarded the Titanic as a first-class passenger. She was traveling with her companion, a 36-year-old piano teacher named Marie Grice Young, along with several exotic chickens from France that they planned to breed in their Westchester mansion. They’d been on vacation in Europe and had chosen to return to America on a ship called the RMS Titanic, which was about to make its maiden voyage, according to Guernsey’s listing.

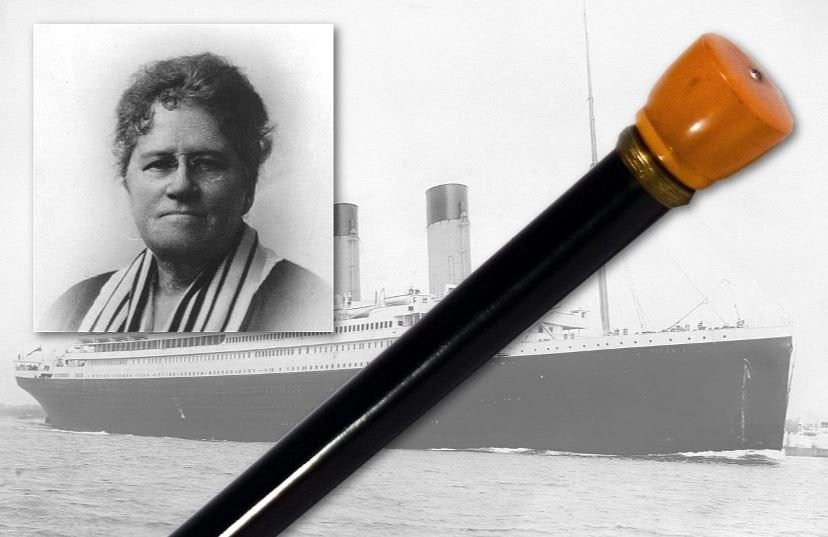

White had injured her foot during her travels, but she’d acquired a rather snazzy cane to help her keep her balance. The enameled black cane looks pretty simple at first glance, but its amber-colored bakelite head—made from the world’s first synthetic plastic—held a tiny, battery-powered light. This technology may seem kitschy by today’s standards, but it was cutting-edge technology in 1912, a mere 33 years after Thomas Edison had invented the electric light bulb.

White was lying in bed on the Titanic that night when she felt an odd sensation, “as though we went over about a thousand marbles,” she later said in her Senate testimony. When she managed to reach Lifeboat No. 8, she found 22 women and four men—nowhere near the lifeboat’s capacity—already on board.

As the group began oaring toward a light in the distance, which likely indicated another ship, it soon became tragically clear that none of the men on the lifeboat knew how to row. These were dining-room stewards, not seamen. According to White, they’d “escaped under the pretense of being oarsmen.” White and the other women soon took over the task.

After about 45 minutes, the Lifeboat No. 8 crew turned back to see if they could rescue other survivors. The night was impossibly dark, and the passengers realized that they would have no way of spotting other lifeboats. “The lamp on the boat was absolutely worth nothing,” White said in her Senate testimony. “I had an electric cane—a cane with an electric light in it—and that was the only light we had.”

White’s cane shone far brighter than any of the lifeboats’ lamps, and she waved it around as Lifeboat No. 8 headed back toward the Titanic’s sinking hull, in search of survivors. Though the cane’s light may have caused more confusion than assistance for nearby boats, it helped White and her crewmates navigate safely back to the ship—just in time to watch it sink. “We sat there for a long time, and we saw the ship go down, distinctly,” White said.

All 26 people on Lifeboat No. 8 survived. After the disaster, White and Young moved in together and shared a home in Westchester County for the next 30 years. When White died, she left Young the bulk of her estate, including the cane. Historians believe White and Young likely had a queer relationship, according to OutSmart Magazine.

“I don’t think my father understood that Ella and Marie Grice Young had a relationship that was more than just friends,” says White’s great-grandnephew John Hoving. “I didn’t put two and two together about their relationship until later in my life.”

After White’s death, her cane changed hands several times. Its recent emergence on the Guernsey block has stoked a feud between two cousins, each of whom claims ownership. It was put up for auction by its current owner, Brad Williams, a great-grandnephew of White’s who says he inherited it from his mother, who in turn got it from her mother, White’s niece Mildred Holmes.

But on July 4, Hoving challenged the auction, alleging that the cane was stolen nearly 50 years ago from his family’s umbrella stand in an Upper East Side apartment. He contends that Holmes gave the cane to his father, not his aunt.

“This cane was part of our family folklore,” Hoving says, “No one had flashlights back then, and my great-great aunt was is in this lifeboat with a bunch of guys who didn’t know how to row.”

Hoving remembers his father parading the cane around for family and friends, telling the epic story of how White managed to survive the Titanic’s sinking. By the early 1970s, the light had nearly stopped working, but the amber head of the cane still emitted a dim sort of glow.

Luckily for would-be bidders, Hoving, Williams, and Guernsey reached a preliminary agreement on July 15. White’s cane will proceed to auction on July 20 as a part of the lot “A Century at Sea.” It is expected to fetch as much as $500,000.

“The fact that this cane still exists is extraordinary,” Hoving says. “I hope it gets displayed somewhere so people can continue to hear the story behind it.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook