Step Inside Brazil’s Museu Nacional, Before the Devastating Blaze

A new digital tour helps visitors jump back in time.

In September 2018, a fire ripped through the Museu Nacional in Brazil, destroying many of the world-class objects in the 200-year-old collection, which held millions of treasures. Video footage captured in the aftermath showed blackened walls and a floor littered with a jumble of ash-colored fragments. The Bendegó meteorite—a five-ton behemoth discovered by a boy in Bahia in 1784—continued to crown its pedestal, less susceptible to flames than the materials scattered below it, many of which were crushed and charred beyond recognition.

While the full portrait of the losses is still coming into focus, some treasures have been recovered. In October, researchers sifting through the wreckage found portions of the bones belonging to the 11,500-year-old skeleton known as “Luzia,” one of the oldest known human fossils in the Americas, which was unearthed in the 1970s. In December, museum researchers said that they had salvaged over 1,500 objects, including indigenous arrows, a Peruvian vase, and a pre-Columbian funeral urn, the Associated Press reported. “The work must be done very carefully and patiently,” Alexander Kellner, the museum director, told the AP.

Meanwhile, the Brazilian government has earmarked R$10 million (roughly US $2.6 million) to rebuild. “We can only hope to recover our history from the ashes,” Maurilio Oliveira, a paleoartist at the museum, told The New York Times, discussing the Luzia fragments. “Now, we cry and get to work.”

It’s sure to be a long process. But while researchers continue to comb through the rubble and take stock of the toll, a newly released digital tour of the museum—undertaken by Google Arts & Culture beginning in 2016—invites visitors to poke around the collection in its former glory.

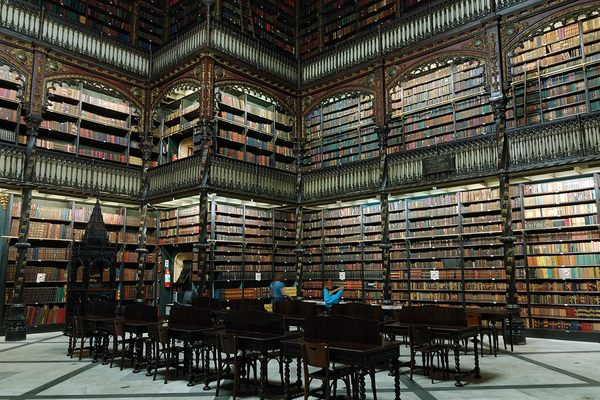

Digital visitors can enter the museum, which was housed in a former palace, and spin around to take in 360-degree views. Because the tour uses Street View imagery, it evokes the experience of seeing the objects at eye-level—almost as though you were wandering the airy hallways, passing through the arched doorways, and stooping to peer at vases held behind glass. The Google project also includes some digital exhibitions, such as a roundup of artifacts found in the sambaquis, the heaping mounds of shells, waste, tools, weapons, and more from fisher-gatherer cultures that lived along Brazil’s coast thousands of years ago.

Here are a few of the artifacts you can appreciate online, no matter what turns up in the ashes:

Handsome handiwork

This vase was made by artisans of the Marajoara culture, whose members lived near the shore of the Amazon River in Brazil between roughly 400 and 1400 A.D. The vase’s spiraling, coursing pattern evokes waves and ripples, and the artifact once sat in a room with many other examples of pre-Columbian ceramics.

A coffin with a story to tell

This plaster-and-wood sarcophagus was made in Egypt for Sha-Amun-en-su, likely around 750 B.C. Researchers have puzzled out a bit about her biography by studying the hieroglyphics on the sarcophagus. Based on those, they’ve concluded that she was a Heset, or singer in a temple to the god Amun in Thebes, where she would have participated in rituals.

Seat of power

This 19th-century wooden seat, featuring elaborately carved sides, was known as zingpogandeme, and was replica of the throne occupied by King Kpengla, who ruled Dahomey, in present-day Benin, in the 1770s and 1780s. At the Museu Nacional, it shared a room with other arts of Africa.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook