When Bowling Was a Sport Reserved for Royalty

King Henry VIII famously banned commoners from participating.

King Henry VIII may be most famous for ruthlessly beheading his wives, but he was also keen on rolling other spherical objects: namely, bowling balls. Henry VIII and his courtiers were known to be fans of lawn bowling, which involved tossing a “bowl” or ball across open lawns in royal gardens.

The Tudor-era bowling ball above, recently discovered in what used to be the moat of King John’s Court manor house thanks to digging work related to London’s Crossrail project, is a remnant of one of the British monarchy’s favorite pastimes.

The English didn’t invent bowling. The first precursor of the sport is said to date to the Egyptians and Romans, who would stuff leather balls with corn, as Roy Shephard notes in An Illustrated History of Health and Fitness. In England, historians trace the sport back to the late 13th century, as open greens or “bowling greens” became more of a common feature in gardens.

Bowling was just one of many sports that were played in these courts. During the early modern period, sport was typically reserved for elites and even governed by the monarchy. Games such as tennis, wrestling, jousting, and bowling were not only for physical fitness, but opportunities for dukes and lords to socialize and exhibit power.

“If used carefully, [sport] could propel a gentleman to the heart of power,” writes James Williams in the journal Sport in History. “For the early Tudor gentlemen, sport could be a ‘deadly serious game’ with an essential social and political role.”

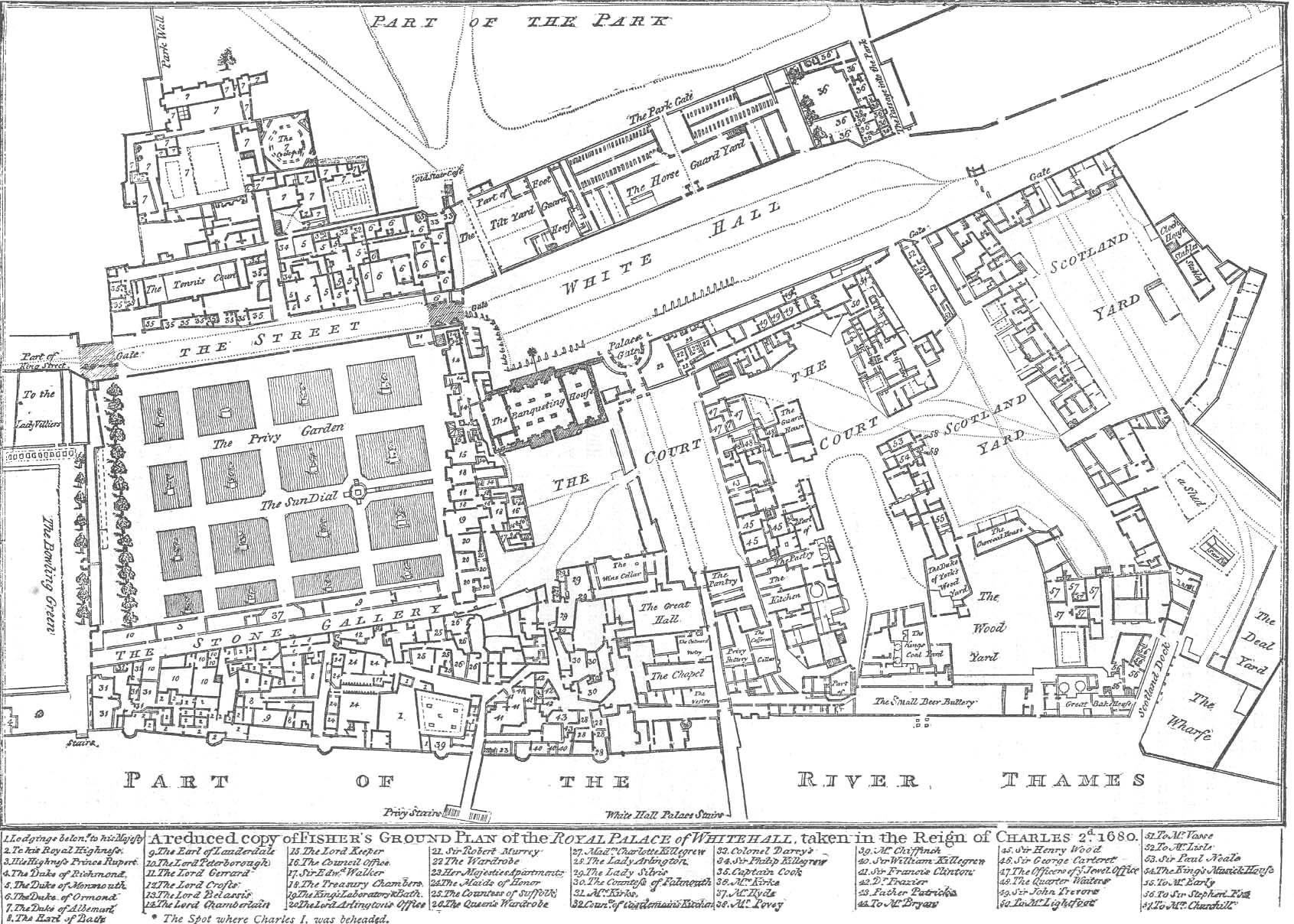

Special structures and venues were an expense only the wealthy could afford. Henry VIII, an avid sportsman, attached a number of sporting venues to his palaces. Hampton Court, Nonsuch Palace, and Whitehall boasted tiltyards, cockpits, and bowling alleys. The complex at Whitehall was particularly elaborate, including four indoor tennis courts, a jousting yard, a cock-fighting and bear-baiting pit, and a bowling green.

There were many different types of lawn games that involved rolling a bowl and hitting a pin or cone, such as bocce and nine-pins. One of the earliest forms of bowling was a game called “cones,” in which two small cone-shaped objects were placed on two opposite ends, and players would try to roll their bowl as close as possible to the opponent’s cone. The game “kayles”—later called nine-pins—usually involved throwing a stick at a series of nine pins set up in a square formation, though sometimes players would roll a bowl instead. Similar to the ten-pin bowling commonly played today, bowlers would aim to knock down all the pins with the least number of throws. Sometimes, the game would feature a larger “king pin” in the center of the square. If that was knocked down, the player would automatically win the game.

Choosing the proper shape and type of bowl was important depending on the turf, as Joseph Strutt notes in The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England. Flat bowls were best for alleys, round biased bowls (a ball with a weight on one side) gave an advantage on open grounds, and round bowls were selected for greens that were plain and level.

The sport was widely popular. Local taverns arranged bowling matches in halls or the village green. Gambling was also common. One account in 1648 reported that Sir Edgar Hungerford had lost his entire estate while betting on a bowling match.

More than one British monarch tried to ban commoners and peasants from participating in bowling, along with other sports, arguing that they were a waste of time and encouraged gambling. In 1477, King Edward IV decreed that for commoners, playing sports was a finable offense:

“whosoever shall occupy a place of closh, kayles, half-bowle, hand-in, hand-out or queck board shall be three years imprisoned and forfeit £20, and he that will use any of the said games shall be two years imprisoned and forfeit £10.”

Similarly, in 1511, King Henry VIII tried to make the sport even more exclusive. He declared that bowling was illegal for common people, and that “no manner of Persons could at any time play at any Bowl or Bowls in Open Places out of his Garden or Orchard.” Those who broke the law would receive a statutory fine of six shillings and eight pence. Though according to Shephard, noblemen who owned property valued at more than £100 could obtain a “bowling license” to play. It would take centuries for these laws to be amended.

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook