The Plant Breeder Who Minted a New World of Flavor

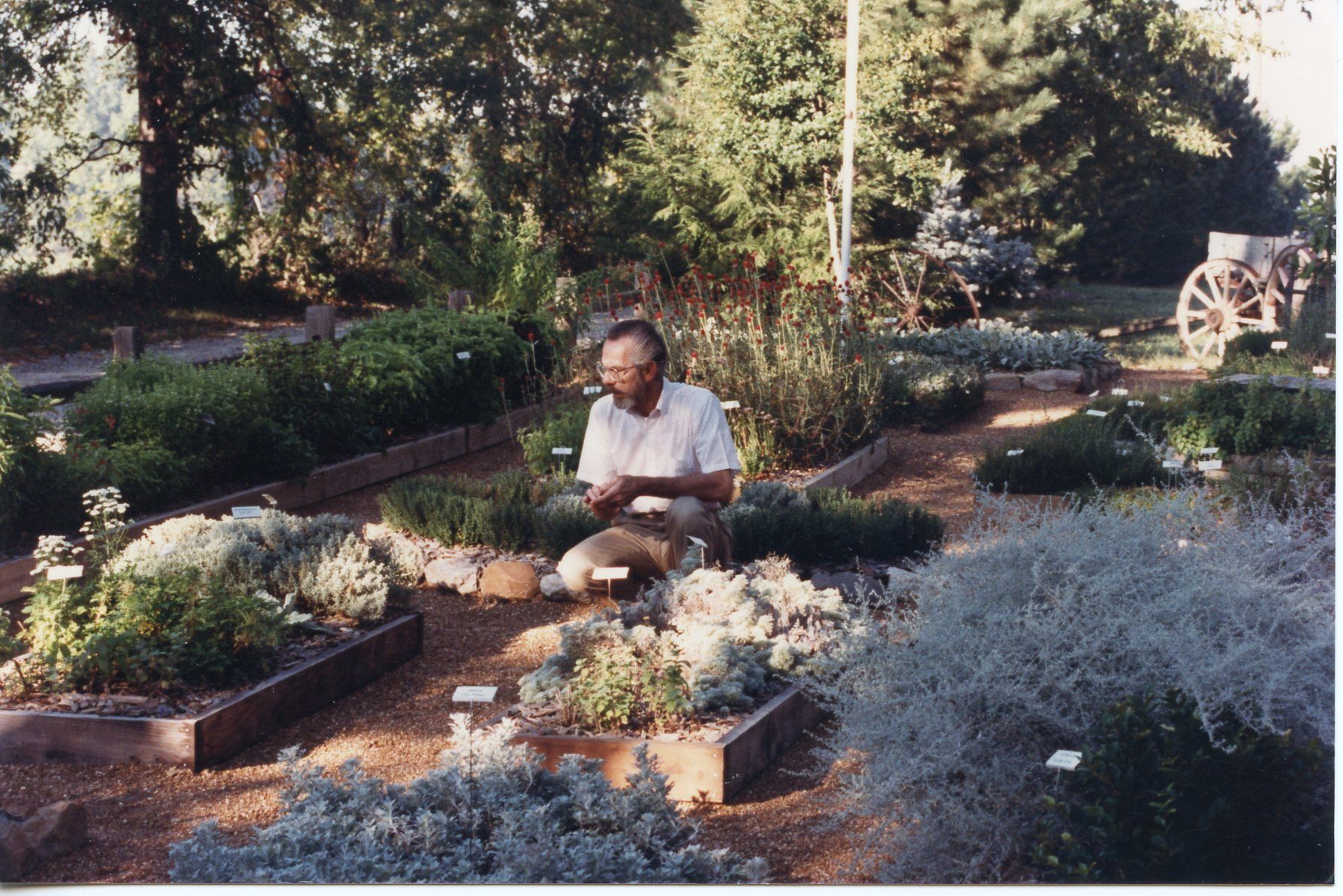

Jim Westerfield created dozens of new culinary mints in his Illinois garden.

Those who knew Jim Westerfield described him as a renaissance man. A talented, self-taught musician and composer who knew everything about antiques from the American Revolutionary period. An entrepreneur who, together with his wife, created the Westerfield House, a popular inn and restaurant in rural Illinois. An obsessive culinary gardener and amateur botanist.

But Westerfield’s true passion was breeding new types of mint—he created dozens of new varieties over the course of his lifetime. The names of his mints hint at their flavors: “Sweet Pear,” “Candy Lime,” “Marshmallow,” and “Candied Fruit.” His crowning achievement was “Hillary’s Sweet Lemon Mint,” one of the relatively few mint varieties ever to be granted a United States patent. Today, Westerfield’s mint varieties are widely propagated by both commercial growers and home gardeners. Online, bloggers review his mints, highlighting their unique attributes, and gardeners swap tips on forums for finding harder-to-locate varieties. Westerfield expanded the boundaries of the culinary mint world, giving gardeners and connoisseurs a palette of mint flavors never before envisioned.

An Illinois native and the youngest of eight children, Jim Westerfield was born in 1935 in the midst of the Great Depression. His fascination with culinary gardening began early. At the age of 10, he found a tattered old magazine with an article entitled “Grow Your Own Seasonings,” and became enthralled with herbs. Growing up in an area that was hard-hit by the Depression, Westerfield spent hours in the library to keep himself out of trouble, devouring books on botany, herbs, and plants. “Jim came from a neighborhood where everyone had a vegetable garden. He started growing basil when he was about 11,” says his niece, Lori Crider. “He was just hooked from then on.”

After high school, Westerfield had hoped to attend college, but his father’s untimely death led him to enter the grocery business to support his mother. While working in the industry, Westerfield married, had a son, and travelled to Nashville on his days off to collaborate with musicians, composing and arranging music for pop-rock bands. His songs were featured in both America and Europe, and one of his compositions, “Another Time (Another Place),” was a “spotlight” single on the Billboard charts in 1965. In 1984, inspired by a bed and breakfast he and Marilyn had visited, Westerfield moved with his family to a rural property near Freeburg, Illinois. There, they built a log cabin to house a restaurant and inn, which they dubbed the Westerfield House.

As soon as construction was completed, Westerfield began breeding new types of mint in the Westerfield House gardens. Kneeling among garden beds surrounded by Illinois cornfields, he’d take pollen from male mint plants and carefully brush it into the flowers of female mint plants of another variety. His combination of remarkable patience and careful record keeping enabled him to create mints that evoked a broad range of flavors ranging from fruity notes, to undertones of hazelnut, to aromas of oregano and thyme.

His passion for unique flavors separated Westerfield from the more commercial plant breeders, who use the same hybridization process but focus on varieties that show potential for either higher essential oil yields or increased resistance to disease. For Westerfield, breeding mints with unheard of flavors that could be used in new ways was the primary goal.

As the popularity of The Westerfield House grew, Westerfield began selling his mints and other herbs to the public. “He had a little greenhouse and garden shop,” says his niece. “People would come from miles away just to buy a pot of his mint.” The Westerfield House also self-published several cookbooks that featured Westerfield’s mints. “The herbs were in everything we made at the restaurant,” says Crider, who helped them open the restaurant and worked there for years. “I don’t think there was a dessert that came out of the kitchen that didn’t have some of Jim’s mint in it.”

At its peak, the Westerfield House garden contained approximately 140 varieties of herbs, including over 40 different types of mint. The Canadian plant grower Richters Herbs began offering Westerfield’s mints for commercial sale, making his varieties available worldwide. Westerfield mints were featured in garden forums and herb publications, and highlighted in media articles and on television.

Of all the varieties that he bred over the years, Westerfield’s favorite was “Hillary’s Sweet Lemon Mint” (Mentha Dulcia Citreus), which he patented in 1993. It took him seven years of experimentation to create Hillary’s Sweet Lemon: a cross between apple mint and lime mint. The resulting herb has a mild flavor, with fuzzy silvery-grey leaves, and a whisper of lemon along with the classic mint aroma. It was often featured in cookies, cakes, and beverages at the Westerfield House. Westerfield named the mint in honor of Hillary Rodham Clinton, who was First Lady at the time, and the story of Hillary’s Sweet Lemon Mint was picked up by newspapers. Illinois Representative Jerry Costello (a regular at the Westerfield House restaurant) became interested in the mint, and in 1993, Costello formally presented a plant of Hillary’s Sweet Lemon Mint to the First Lady in Washington, who wrote a letter of thanks to Westerfield for “the wonderful gift.”

The Westerfield House closed in 2002 when Westerfield and his wife retired, but he continued to develop new strains of mint up until he passed away in 2013. His legacy lives on through the unique mints he created that are planted in gardens around the world.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook