The Risks and Rewards of the Remarkable Desert Truffle

Mysterious to scientists, dangerous for foragers, and coveted by gastronomes.

In good years, fall and winter thunderstorms drench the deserts east of the Mediterranean. In early spring, the soil cracks in some places, the swelling signs of desert truffles below. An age-old harvest begins.

In the Middle East, humans have foraged these unique mushrooms for millennia, scanning broken earth for protein-rich knobs to eat, sell, or use in medicine.

They haven’t stopped of late, despite the threat of kidnappings and landmines. For some inhabitants of these deserts, the truffles are worth the risk.

Scientists who study desert truffles, meanwhile, describe them as fascinating and “mysterious.” Over the last two or so decades, they have tested ancient wisdom about this largely underappreciated specimen, developing theories about its remarkable ability to adapt and thrive in some of Earth’s driest places.

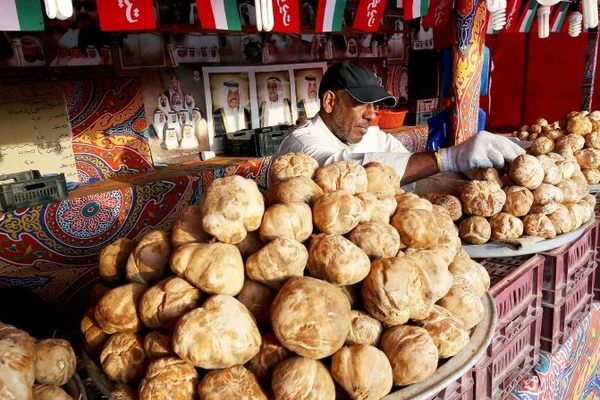

Gather a bounty of desert truffles, haul them to market, and they typically bring in anywhere from $3 to $30 a pound in Iraq and Kuwait. In Saudi Arabia, these revered fungi reportedly fetch at least $84 per pound.

Known as kama in Arabic, desert truffles are so popular that Kuwait has a seasonal market dedicated wholly to them, and in Iraq, springtime markets exclusively for truffles pop up in the southern part of the country.

These days, desert truffles at such markets are often imported from elsewhere in the region—Iran, Saudia Arabia, Libya, Morocco—given the dangers of procuring them locally. A little over two years ago, unidentified gunmen in Iraq’s Anbar Province kidnapped a dozen foragers. Just a few weeks earlier, Islamic State militants had kidnapped and killed three brothers who were reportedly searching for desert truffles.

There are other horrors, like landmines left from the 1991 Gulf War. “A while ago, someone died,” Mohsen Farhan, who forages for truffles with his family in the Iraqi desert, recently told Reuters.

Six or seven years ago, a Syrian man was collecting truffles in a gorge in northern Syria, in an area where families used to picnic. He saw a body stuck on a ledge, he told human rights investigators, who determined the gorge was being used to dump bodies.

For some, the dangers are too great. In 2017, Ibrahim Hussein and his family, who used to camp out in the eastern Syrian desert every spring to hunt for truffles, gave up, concerned about U.S. drones and ISIS sleeper cells, he told the Wall Street Journal.

But these hardships are simply the latest chapter in humans’ long relationship with desert truffles, which began millenia ago: Archaeologists have found mention of desert truffles in cuneiform on clay tablets unearthed at an excavation of a 4,000-year-old Amorite site in eastern Syria. The food from God described in Exodus as “manna” might, some scientists have argued, be desert truffles.

Despite its esteemed history, the desert truffle remains underappreciated outside the region. It has often been dismissed by those who prefer their truffles European, but that is their oversight, because a desert truffle is not supposed to be a European one, overwhelmingly pungent and heart-stoppingly expensive. Rather, it’s a nourishing seasonal staple that is as understated as it looks (plenty of people have mistaken truffles for rocks).

Desert truffles in one genus, Terfezia, come in all shades of brown, even black, and are slightly softer than a potato. In the other, Tirmania, the truffles are white and have a mushroom-like texture. Their taste is said to be subtle but distinct, like mushrooms but meatier, and they can carry flavors from whichever aromatics and spices they are cooked alongside. A single desert truffle clocks in between one ounce and ten, sometimes with multiple lobes separated by creases full of sand.

After a day’s work, a forager might roast them over coals. Urban connoisseurs might boil or fry them in butter, or with chopped onions and a dash of turmeric, or scramble them with eggs to put in a pita sandwich. Some grill them, kabob style, between sizzling hunks of animal fat. Another popular option is cooking them with camel’s milk to make soup.

Varda Kagan-Zur, a professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel (she’s retired from teaching but still involved in research), remembers her first encounter with desert truffles. It was around 1983, a few years after she’d earned her PhD in plant physiology. At a market in Beersheva, she noticed Bedouin selling something that resembled European truffles.

“But when I started to read about them [desert truffles], I learned that they were inferior,” she recalls. That characterization, she came to realize, was because her information came from European sources, where truffles were primarily used as a condiment—a few shavings are all a dish needs. Yet she could see that locals valued them highly. She began to study them.

Today, mycologists study desert truffles all over the world. Their range includes not just the Middle East but also arid and semi-arid lands in North Africa, the Kalahari Desert, southern Europe, eastern Europe, Australia, China, and even North America.

“There is a lot of interest in desert truffles,” says Kagan-Zur. Some people see them as a potential crop that could thrive in a changing climate. For others, the desert truffle holds culinary intrigue.

As for scientists, “we have accumulated a lot of knowledge, but not enough,” on both a scientific and practical level, Kagan-Zur says. Cultivating desert truffles remains a challenge, and many scientific papers about Tirmania or Terfezia lament something along the lines of “the lack of basic knowledge of their biology at all levels.”

Desert truffles typically grow in conjunction with the shrubs and annuals of the genus Helianthemum, or the rock rose. Their thin fungal filaments—collectively known as the mycelium, individually as hyphae—become intertwined with the plant’s roots, sharing nutrients from the soil, likely in exchange for sugar from the plants.

Mycologists don’t know precisely how desert truffles have adapted to sandy surroundings with minimal rain. But one possibility is the unusual ways their hyphae interact with the root cells of their host plants. Some fungi are endomycorrhizal, meaning that their hyphae are practically embedded in cells. Others are ectomycorrhizal, staying outside cell walls.

Desert truffles, it turns out, can be both.

Research suggests that the relationship the truffles develop with their hosts depends on the weather, according to Kagan-Zur. After a dry summer, fungal filaments tend to penetrate a host’s root cells in typical endomycorrhizal fashion. But when rains arrive, the hyphae pull back.

“It does seem to have a connection with weather conditions, but no one has shown the sequence very definitely,” Kagan-Zur cautions. “We don’t have any proof.”

What scientists are more confident about is that the timing of rain is as important as quantity for truffle development. If the rains arrive too late, the host plant will not establish itself well, and neither will the mushroom.

Another curiosity is the relationship between lightning and truffle formation.

“The stories go that years with lots of storms, thunder, lightning, will be good years for truffles,” Kagan-Zur says. Somehow, the same legends that have developed across the eastern Mediterranean can also be found as far away as present-day Botswana, in the Kalahari desert. Their independent arisal suggests an element of truth to those stories.

Just because they haven’t been verified, Kagan-Zur says, doesn’t mean they’re untrue.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook