The Harsh Reality of Food for ‘Little House’ Pioneers

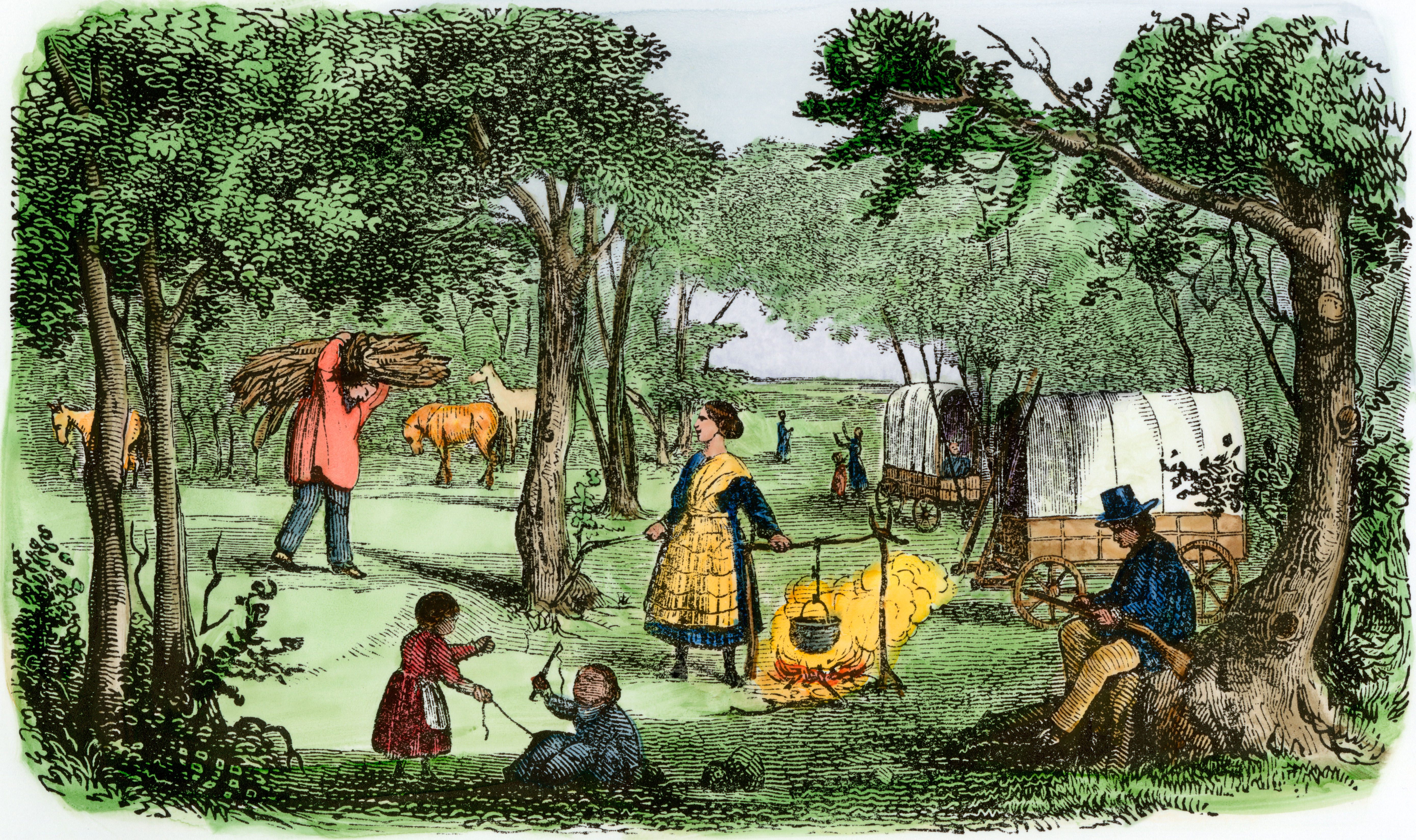

On the American frontier, dinner might have been vinegar pie, bear meat, or nothing at all.

There is perhaps no better-known account of American pioneer life than the Little House series of children’s books by Laura Ingalls Wilder, which was subsequently adapted for the stage and big screen. Over the course of nine books, set between 1870 and 1894, Wilder recounts a fictionalized version of her childhood and adolescence as the Ingalls family moves west, variously living in Wisconsin, Kansas, Minnesota, South Dakota, and Missouri.

Nowadays, however, the books are divisive. Many readers see them as a racist relic worth removing from the children’s literature canon altogether. In June 2018, in fact, the American Library Association excised Wilder’s name from the Children’s Literature Legacy Award book prize due to these concerns. Yet there are still those who love the books, celebrating them in memoirs, blogs and listicles alike—often with a particular focus on the novels’ food.

Mealtime scenes are some of the most memorable in the books, laid out meticulously in calm, deliberate prose. A salted pig’s tail, sizzling over the flames, is so good that the main character, Laura, scarcely minds that she’s burnt her finger. Hard candy, made with boiled molasses and sugar, is made by drizzling the dark syrup “in little streams” onto “clean, white snow from outdoors.” A candy heart, printed with red letters, is “wrapped carefully in her handkerchief until [Laura] got home and could put it away to keep always. It was too pretty to eat.”

But even those celebrations of food show why these books need reconsideration. For the generations of readers who grew up with these stories, these romanticized accounts sometimes leave readers with a false impression of how good the Ingalls family had it.

“[The Little House books] are designed to codify the myth of the self-sufficient pioneers, pulling themselves up by their bootstraps and living off the fat of the land,” writes Constance Grady for Vox. But “self-sufficiency” often actually meant periods of hardship and famine, with families struggling to survive long, difficult winters. Yet that doesn’t always come across. Instead, with the possible exception of The Long Winter, the books err towards what Grady characterizes as “an almost pornographic pleasure in describing butter churning and hog slaughtering and corn harvesting.”

Even the individual dishes, however lovingly described, may not stand up to scrutiny. Food writer and Atlas Obscura contributor Anne Ewbank remembers an account of homemade vanity cakes particularly acutely. This proto-donut still lingers in her imagination and, as a child, seemed to her “the most delicious thing in the world,” she says. “I haven’t read these books in more than a decade, but the memories are so vivid to me.” Yet modern reconstructions suggest that these treats, no more than unsweetened scraps of fried dough, are bland and unappealing.

Pioneer food was often stodgy, plain, or altogether absent. While Laura’s family is concerned throughout the book with packing away stores to make it through harsh winters, Wilder tends to gloss over the risk of famine or even death. In summertime or fall, pioneers might feast on bear meat (Laura’s favorite), buffalo, venison, elk, and antelope, unconstrained by the big game laws of the Old World. But in winter, when nothing grew or could be hunted, pioneers were vulnerable.

Families like the Ingalls family had it especially tough. As historian Erin E. Pedigo observes, Pa’s “dreams of wide open space with few neighbors and accumulated wealth from working the land were far bigger than his abilities,” and his family paid the price. Out on the open frontier, or deep in the woods, there was no market economy or community to fall back on during difficult months. In On the Banks of Plum Creek, a plague of grasshoppers destroy the family’s wheat crops and force them to move. Later, in The Long Winter, Wilder describes a brutal 1880 winter in De Smet, South Dakota, that lasted from October to April.

Though a fictionalized account, this winter was one of the worst on record in the Dakotas. “The first blizzard, which raged for three days, came in early October,” writes Constance Potter. “By Christmas the trains had stopped running.” Wilder describes the isolated Ingalls family counting the days until food from the outside world could reach them, as they watched their own supplies dwindle. Laura, then a young teenager, does calculations in her head about their diminishing stores: “ … half a bushel of wheat that they could grind to make flour, and there were the few potatoes, but nothing more to eat until the train came. The wheat and the potatoes would never be enough.”

Eventually, Ma finds a way to turn their seed wheat into flour with a coffee grinder, and then bakes it as bread—though, as Pedigo notes, it’s crude, tasteless, and, however horrid, “weirdly perfect for this brutal winter.”

Yet when the famine breaks, and the spring comes, the difficulty of the past months seem suddenly a distant memory. In May, the family finally receives their Christmas package, replete with 15 pounds of frozen turkey in a mass of brown paper, and cranberries rolling about in the bottom of the barrel. As they sit to eat, Pa thanks the Lord “for all Thy bounty.” The long months in which people narrowly avoided starvation are written off as a long, hard winter, and part of the lottery of pioneer life. Pa begins to play his fiddle, and all is suddenly well.

What is not explored in the books, however, is whether their intrepid pioneer lifestyle merited the risks. Ma and Pa spend almost all their time simply trying to keep the family alive. For Ma, each day is taken up with menial upkeep of the home (washing, ironing, mending, churning, cleaning, baking), usually while pregnant. Meanwhile, Pa is out in the woods, hunting whatever he can find and avoiding the wrath of hungry bears. By contrast, salt-rising bread, sugar cakes, and maple syrup candy are perhaps prominently featured in the books precisely because they were such rare occurrences.

When there was food to be had, settlers’ actions had an environmental toll. Unrestricted fishing and hunting—one day, Pa returns home with a literal “wagonload of fish”—diminished the plentiful resources that drew settlers. By 1890, buffalo numbers were visibly reduced, for instance, while by 1900, the American passenger pigeon, which had been the most common bird in the country, was extinct. In the books, this devastation, and the consequences for Native Americans who were being pushed off their land by settlers, go unmentioned.

The references to Native Americans and other people of color in the books, in fact, are especially troubling. Characters express their hatred for the people they were dispossessing (“The only good Indian is a dead Indian,” a neighbor* exclaims), while a description of a minstrel show concludes: “When the five darkies suddenly raced down the aisle and were gone, everyone was weak from excitement and laughing.”

There may be things worth celebrating about the Little House books—the lucid account of a little girl tasting lemonade for the first time or a table groaning with vinegar pie and Swedish crackers. But the world they construct whitewashes much of the harshness of pioneer life, while ignoring the harm these settlers did to the people and environment around them. Like the vanity cakes, they sound great on the page, but may well be much less appetizing in real life.

* Correction: This story originally attributed the phrase “The only good Indian is a dead Indian” to Ma, when it was a neighbor who said it.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook