Abalonia: The Island Nation That Never Was

It was meant to be a seafood paradise.

In 1966, California newspapers began reporting a startling story. A B-movie actor and several California businessmen were making plans to build their own island. The chosen locale was 100 miles off the California coast, on a massive, submerged island known as Cortes Bank. Ostensibly, the goal would be to mine a rich vein of seafood, especially abalone. Only an accident kept them from building their island nation. It was going to be called “Lemuria,” the name of a lost continent. But the media coined another, more compelling name: “Abalonia.”

Cortes Bank has long been considered a valuable yet perilous spot. Ships need to dodge Bishop Rock, which lurks a few feet below the surface, marked by a warning buoy. The site fosters a rich environment of sea life, making it a diving destination today. It’s also a legendary surfing site, because Cortes Bank produces some of the tallest surfable waves in the world. For Joe Kirkwood, Jr., Richard Taggart, and Bruce McMahan, the attraction was the sea life: They hoped to build an island outpost where they could harvest and ship seafood plentifully and cheaply. However, they didn’t know about the waves.

The group was an eclectic bunch. Kirkwood was most famous for appearing in film versions of the comic strip Joe Palooka. He was also a talented pro golfer, and owned a bowling alley. Taggart and McMahan were California abalone canners. Also involved, among others, were savings and loan group president Robert Lynell and aquatic expert James Houtz.

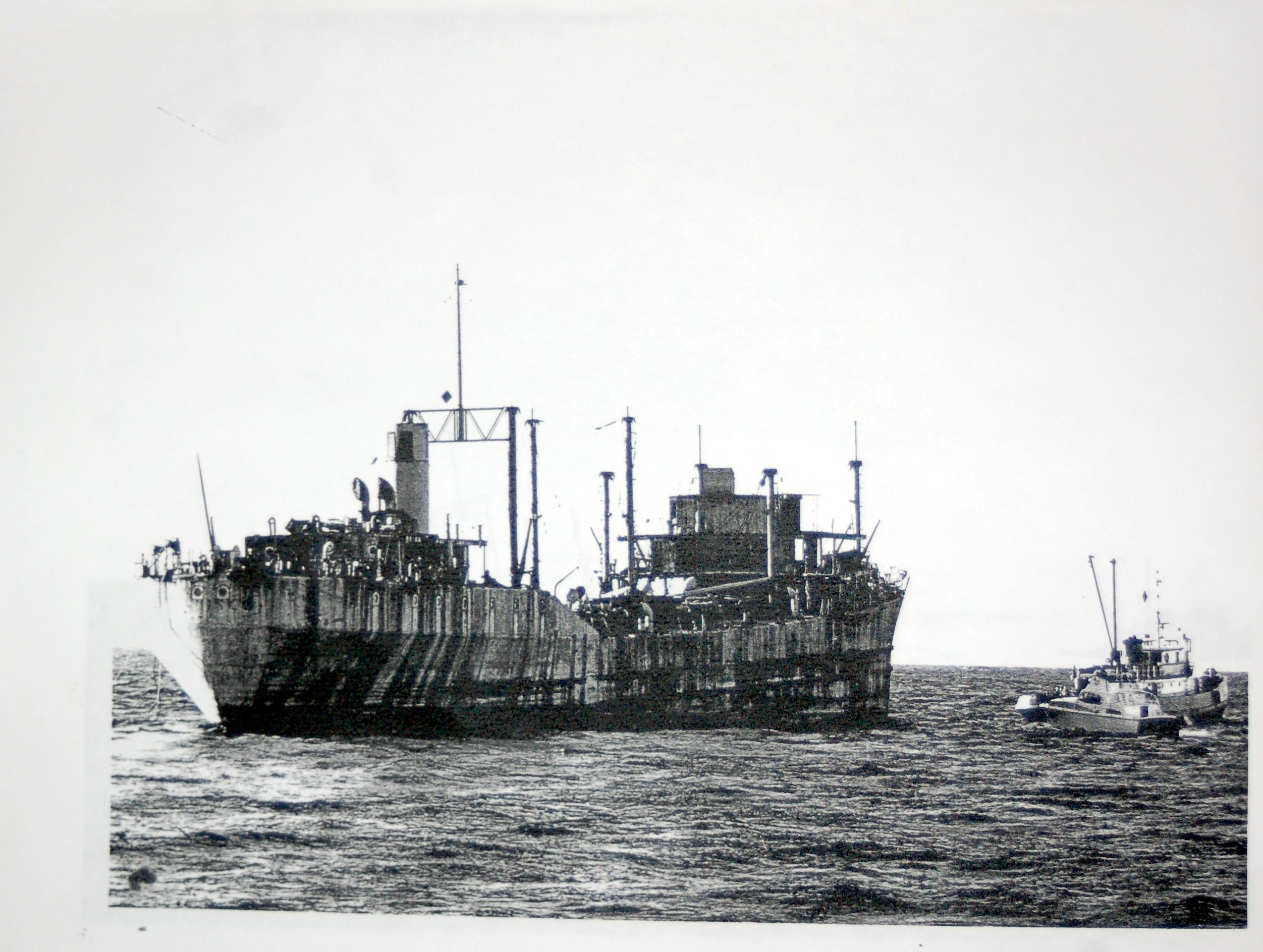

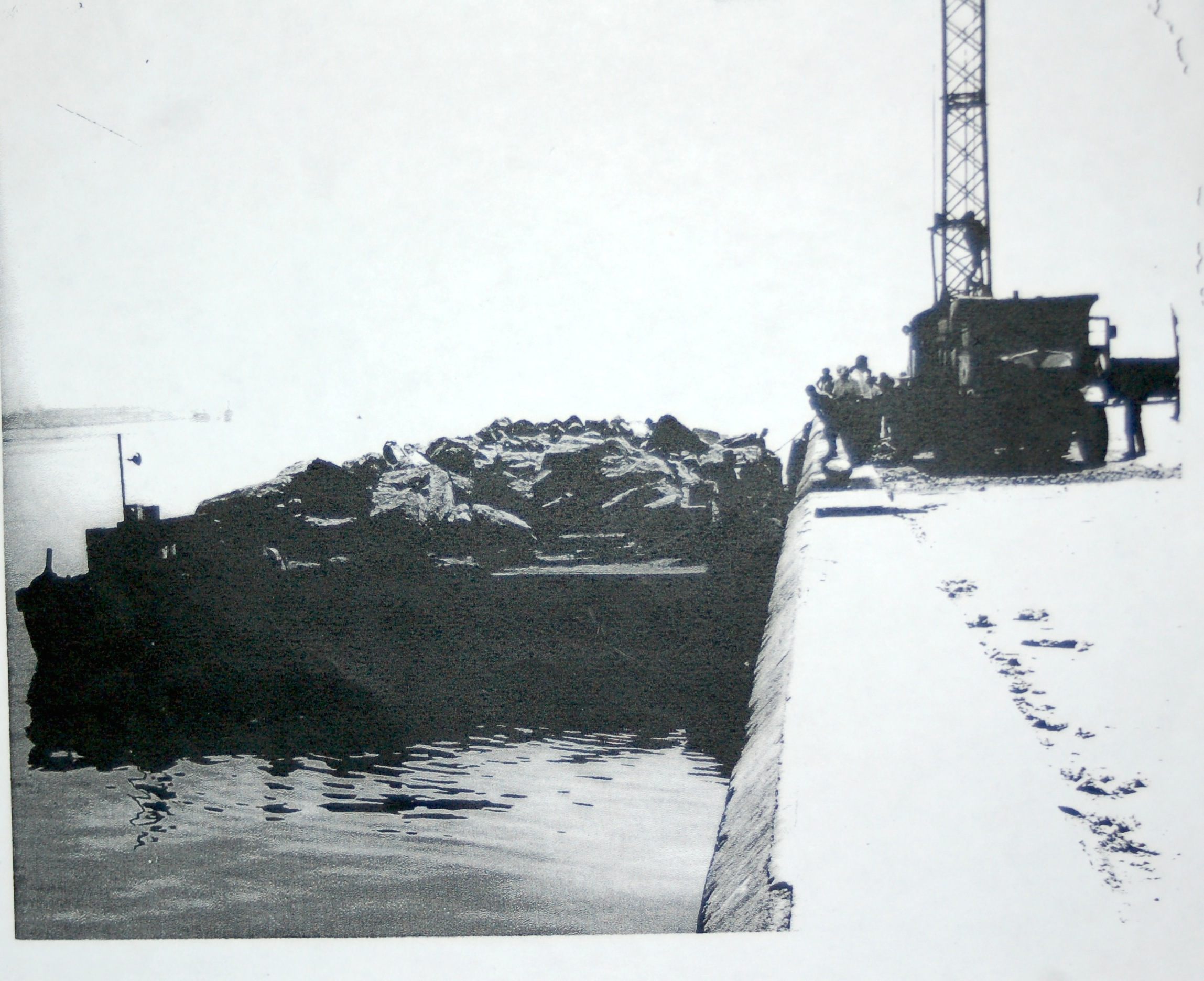

Their plan was to drag a decommissioned World War II freighter, the SS Jalisco, to Cortes Bank and scuttle it in a shallow area. Afterwards, they would haul rocks and even garbage out to the Bank, to create a terra firma from which sweet, fleshy abalone could be harvested. And they would rule their new nation of Abalonia. In October 1966, Taggart gave the verbal equivalent of a shrug to the Los Angeles Times. “I know it sounds fantastic,” he said, “But we’ve consulted experts in international law and they say there’s nothing to prevent us from starting our own country if we want to.”

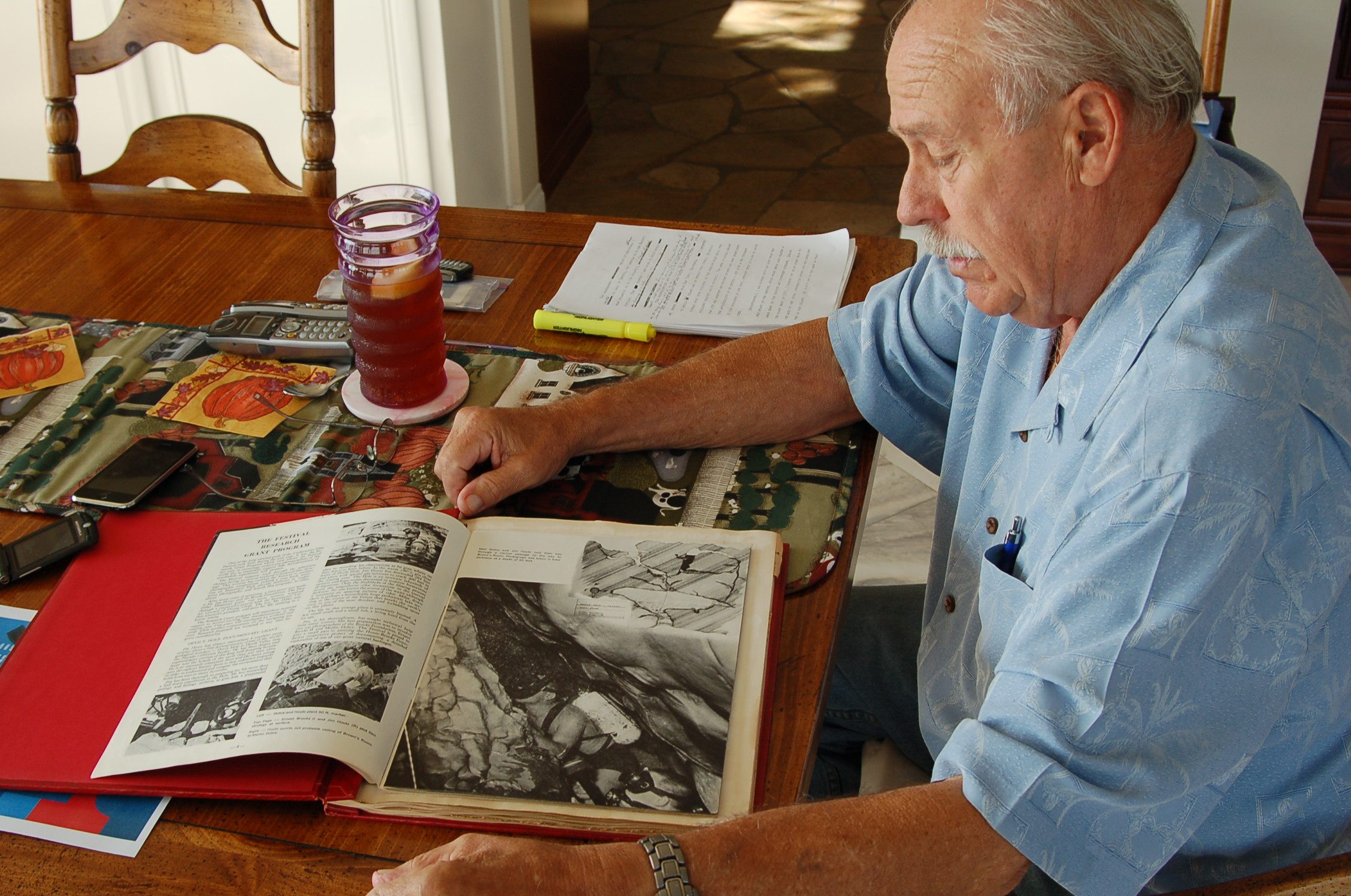

Much of the history of the “Abalonians” has been compiled by a journalist, who also coined the term “Abalonians.” In 2011, Christopher Dixon published Ghost Wave, a history of Cortes Bank and the explorers, treasure hunters, and surfers obsessed with it. One chapter was devoted to the Abalonia tale. “The idea of someone trying to resurrect a sunken island is such an American idea to me,” he says.

By the time Dixon was writing his book, many of the Abalonians had died or gone to ground. Trying to find Kirkwood or someone associated with him was a bust. Until one day, someone anonymously sent him a package. Inside was a scribbled-over manuscript and fistfuls of photos of the Jalisco. The manuscript, says Dixon, was Kirkwood’s account of the dramatic sinking of the freighter and his own near-death, which he had apparently written up for Sports Illustrated but never published. Even better, he soon got a call from James Houtz, who was on the Jalisco that fateful November day.

“You’re really taxing my brain, kiddo,” Houtz says when I reach him at his home in Dana Point, California. Now 79 years old and retired, he took a break from wrangling grandchildren to tell me how he joined the Abalonia venture. A diving and underwater demolitions expert, Houtz had served in the Navy. A self-professed thrill-seeker, he gained fame diving Death Valley National Monument’s Devil’s Hole, a geothermal pool that’s home to the world’s rarest fish. His experience turned somber when, in 1965, two young divers disappeared into its watery depths. Houtz was flown in to find them, but only found a mask. The publicity around the tragedy led to Houtz receiving a call from Kirkwood.

“It was nuts,” Houtz says of Kirkwood’s plan. But he was young and daring, only in his late 20’s. Soon, he was in, intrigued by the challenge. “In my opinion, the impossible takes just a little bit longer. A little bit more thinking.” And, of course, he wanted “a cut of the pie.” Serving as both an aquatic expert and financial backer (he took out a second mortgage on his house), Houtz says he was the one who came up with the idea of scuttling a freighter to build the base of Abalonia. The team found the Jalisco in a “mothball fleet” up in Berkeley. After stripping the ship of everything that could be sold for salvage, it was outfitted as a seafood processing enterprise. By planting the ship near Bishop Rock, the shallowest part of the Bank, fisherman could start harvesting seafood right away.

The dream of Abalonia was expansive. The spot would also be a hive for commercial fishermen, Kirkwood believed, and they could build a runway for planes. Ships could stop to refuel, and there could even be gambling. (Kirkwood denied the allegations that he wanted to build a casino, though Houtz, decades later, confided that he was considering it.) Even building the island would be subsidized, since Kirkwood claimed he was teaming up with City of Los Angeles to build Abalonia out of the city’s trash. It seemed like an impossible dream, but Kirkwood had a way of making it seem possible. Houtz remembers Kirkwood as boisterous and extremely charismatic: He had movie-star looks and “hair most guys would die for,” Houtz says. But Houtz also says that Kirkwood had an irresponsible streak, something that may have sunk Abalonia.

In Ghost Wave, Dixon conjectures that Kirkwood kickstarted the Abalonia venture in a rush, fearing the federal government would bring it to a halt. At the time, Houtz noted that there was a storm on the coast of Japan, but thought it wouldn’t have too much of an effect. On November 13, the Abalonians and their crews left out of the Balboa Bay Club late in the evening. The SS Jalisco was on its way, from where it was docked far up north in Richmond, California.* Barges full of rocks, provided by McMahan, were scheduled to follow soon after.

Houtz had already been to the Bank, scouting for the ideal way to lay the ship down. He had set down a runway of buoys, and with two anchors and long chains, he planned to put the Jalisco into a precise spot before scuttling it. While he had seen some of Cortes Bank’s large swells, putting down the planned “Volkswagen-sized” rocks would likely have protected the Jalisco, he says. Ironically, when the Jalisco arrived near Bishop Rock, they floated on a calm sea. “The kind you kind of dream about. It was just so flat and so smooth,” Houtz remembers. But soon, slight swells started rocking the freighter. The effects of the far-off storm, in the form of a massive North Pacific swell, was arriving.

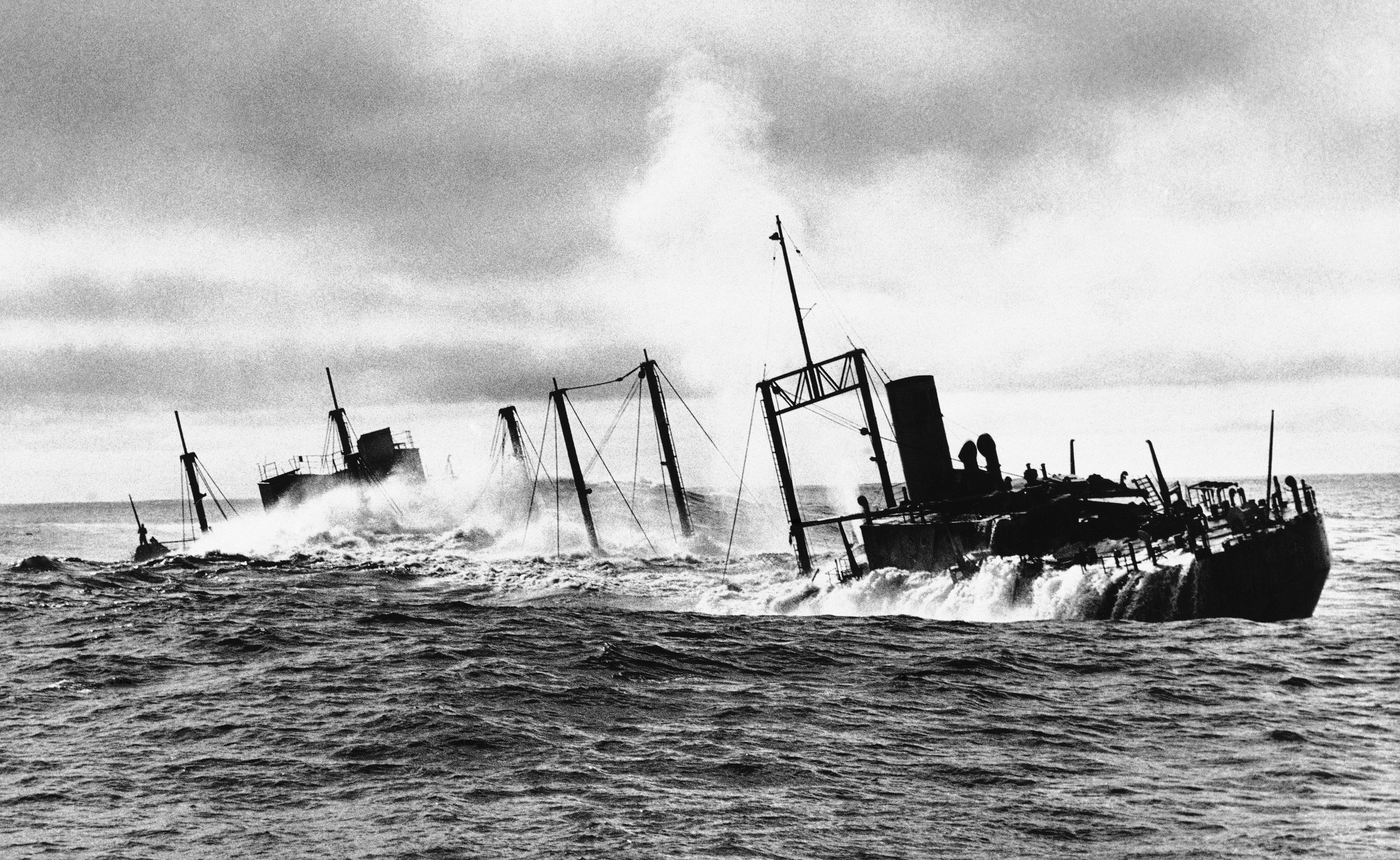

Both man-made and natural disaster struck. In Kirkwood’s account, the Jalisco hit Bishop Rock late Monday night and started to take on water, an accident that he couldn’t be held accountable for. In Houtz’s account (which Dixon confirmed with another living crewman), the action happened the next morning. Houtz says he left much of the preparation of the Jalisco to Kirkwood. When Houtz, Kirkwood, and three others clambered aboard, one of the anchors and much of the vital anchor chain (necessary for situating the freighter) was missing, sold for extra money as salvage. Plus, the diesel engine that powered the chain spool compressor was broken. Putting the freighter in the right place would be nearly impossible. Meanwhile, the swells were getting larger, lifting the Jalisco up 20 feet and dropping it. One swell crushed the freighter against Bishop Rock. “It just thundered. It just crunched. It just hit,” Houtz says. The Jalisco plunged down: The hull had been punctured by Bishop Rock.

The 7,000-ton freighter twisted and turned. A massive wave loomed, then swept over the freighter, snapping the anchor chain. Kirkwood grabbed ahold of a jackstaff, but the others were slammed against the side so hard that Houtz broke a rib. The Whitney Olson, the tugboat that had dragged out the Jalisco, valiantly came close to the side to rescue the trapped men. One man made it over, another jumped into the water. Houtz, Kirkwood, and another man, Will Lesslie, were left on the Jalisco, but not for long.

Kirkwood refused to let go of the jackstaff, insisting that the water couldn’t wash him away. “Joe, you’re out of your mind,” Houtz remembers saying. Another massive wave was coming, a wall of green water. “I thought, holy mackerel.” Heavy barrels of diesel were tossed off the deck: looking as light, Houtz says, as after-dinner mints.

Sheltered behind the ship’s superstructure, Houtz was drenched but fine. But Will Lesslie and Kirkwood were taken overboard. A stunned Houtz, wearing a life jacket, leapt into the water and made it over to the Whitney Olson. An almost-drowned Kirkwood was swept beneath the entire length of the Whitney Olson, only to miraculously emerge relatively unharmed. Everyone on the Jalisco escaped with their lives.

The freighter wasn’t so lucky. Smashed by the waves, Dixon writes in Ghost Wave, “the entire superstructure tore completely free of the deck in a colossal mingling of water and steel.” Months passed before it sunk fully beneath the water. Houtz and the others were whisked away, to be interrogated by FBI agents who arrived via helicopter. “The air was let out of the balloon,” Houtz says.

Houtz emerged physically and financially battered. No seafood empire rose from the waves—his investment was shot, and his rib was broken. The Abalonians parted, and Houtz never spoke to Kirkwood again. Kirkwood managed to dodge legal repercussions for the Abalonia affair, though there was a Coast Guard investigation.

The concept of Abalonia may have been mad, but Kirkwood did well for himself, buying a Hawaiian golf course and selling it in 1987 for $50 million dollars. McMahan became a wealthy hedge fund manager whose lifestyle was the subject of tabloids. And maybe Abalonia wasn’t so bad of an idea after all. Another corporation started making noise about building an island at the spot soon after the Jalisco went down. The federal government squashed it by claiming Cortes Bank as U.S. territory.

As for Houtz, he soon recovered and even went back out to Cortes Bank. Occasionally it is clear enough to see San Clemente Island in the distance, he says. But other than the buoy, it’s a vista of empty sea. “It’s beautiful, but it’s eerie,” Houtz says.

Now, Cortes Bank is notorious, the rusted wreck of the Jalisco beneath the water making it even more dangerous for surfers (though it is a lush diving site). Houtz says he wasn’t aware of how massive the waves could get at Cortes Bank. He’s also not sure what would have happened if the Jalisco had been outfitted correctly. “The Jalisco was pretty fragile when it comes right down to it,” Houtz says. But he thinks that if it had been a calmer day, it might have survived long enough to be protected by the incoming rocks. Abalonia could have risen after all.

*Correction: This story previously stated that the Jalisco left from the Balboa Bay Club. It left from Richmond, California.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook