‘À La Mode’ Is a Lonely Survivor of a French Culinary Code

In America, à la Nesselrode and à la Maryland are à la gone.

You don’t have to be French to know what à la mode means. Even at the humble American diner, where Gallic influence is usually limited to French fries and French dips, desserts are tagged with the term. Pies, cakes, and even pancakes and waffles can come crowned with a scoop of ice cream: in other words, à la mode.

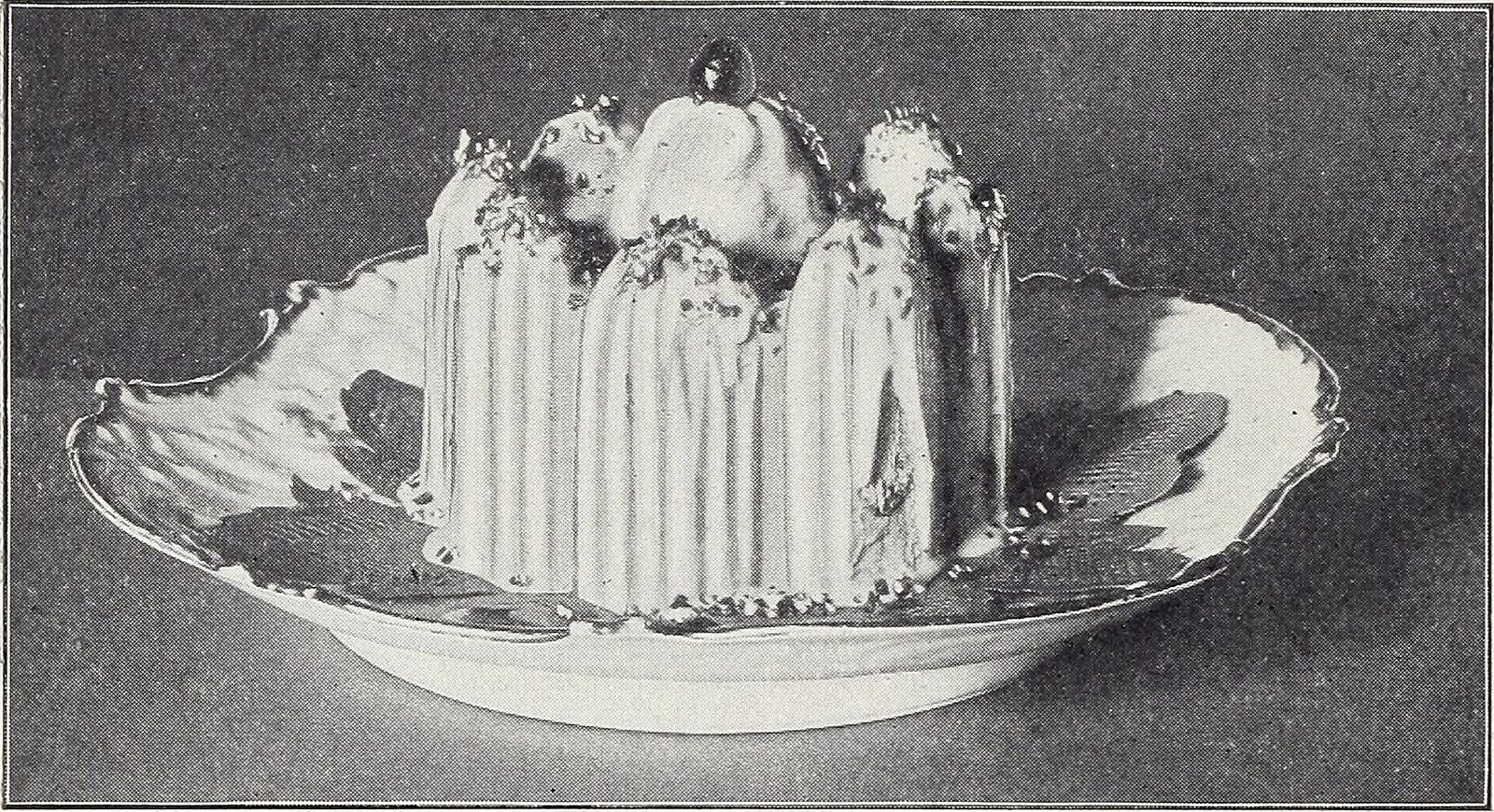

American menus were once replete with such wording. Meaning in the fashion in French, à la mode is a relic of a time when elite diners worldwide used coded terms from classical French cuisine. Today, that system of naming has all but vanished outside of France and French restaurants.

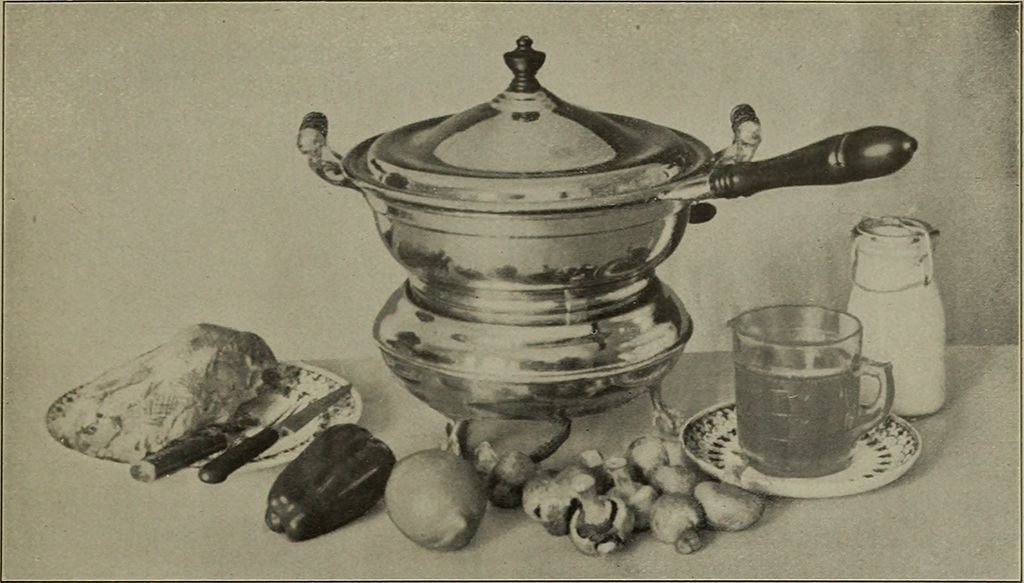

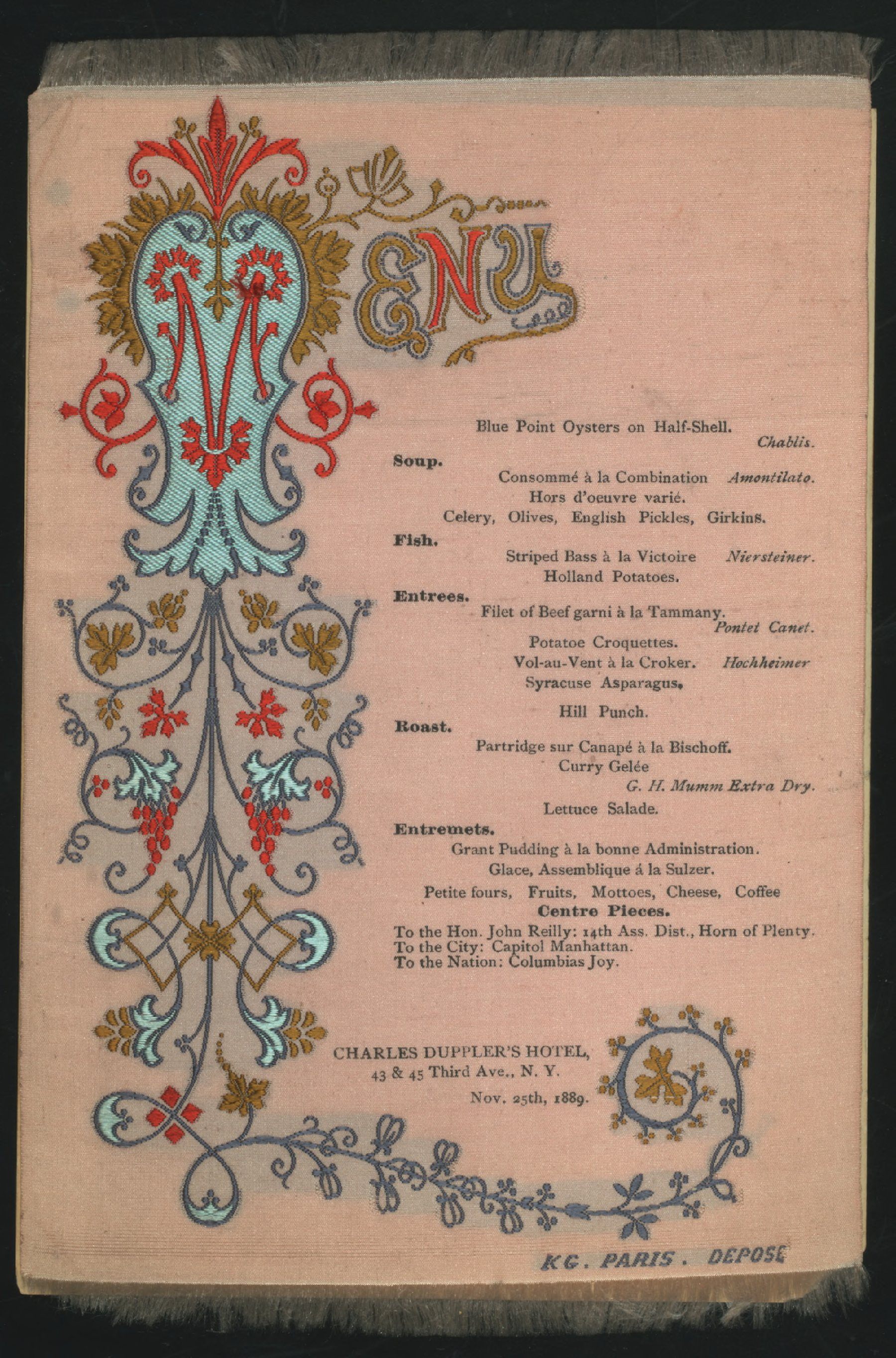

In the 19th century, high-end restaurants in America didn’t lengthily describe their menu offerings. Instead, brief, meaningful wording indicated to diners the sauce and cooking style of their meal. According to Henry Voigt, one of America’s foremost menu collectors and scholars, people who encountered these terms on their menus quickly understood what they meant.

The terminology was vast. Meat à la Bordelaise was served with a red wine and beef broth sauce, originating from the French region of Bordeaux. As for à la Milanaise, that referred to the people of Milan’s custom of breading and frying meat. While geography was a common reference—à la Maryland meant cream and sherry sauce, often applied liberally to Maryland’s former delicacy and current state reptile, the terrapin turtle—it was not a constant. Karl Nesselrode, a Russian politician and military man, inspired an icy dessert made with chestnuts. By the end of the 19th century, chestnut-filled dishes were called à la Nesselrode.

Sometimes the meaning was obvious, as in the cases of tomatoes à la mayonnaise and thé à la Camomille, or chamomile tea. But for dishes such as salad à la Dreamland and croquettes à la Nimrod, the meaning must have been a mystery to everyone but the chef.

In the United States, this culinary code was meant for a privileged few. “Rarely were these terms self-explanatory,” writes Alan Davidson in The Oxford Companion to Food. Often, they were downright opaque. Alexandre Dumas the elder satirized the concept in 1873, compiling a list of the most unusual terms, such as soup à la William Tell, which possibly contained apples. Dictionaries existed just to explain the difference between à la D’Artois and à la Dumas. To those wealthy enough to frequent fine French restaurants, the code was handy. Davidson points out that there was no need for lengthy menu descriptions when a single word could convey if a dish was fried or served with tomato sauce.

By 1900, however, the rule of à la was in decline. Wealthy Americans didn’t necessarily know French, and restaurateurs found it necessary to print translations in English on the reverse side of menus. “By the advent of modernism in about 1910, [à la] usage was a thing of the past in the United States,” Voigt says. It was no longer the mode. When fine restaurants gained steam again after the end of Prohibition, the terminology made a limited comeback in two types of restaurants: high-end venues and expensive yet mediocre establishments. (for “a bit of class,” says Voigt.) Today, Americans are likely more familiar with the similar Italian term alla.

Ordering à la carte and chicken à la King are two more holdouts of this linguistic die-off. As for desserts à la mode, Voigt says he has no explanation for the term’s hardiness, or even its origin. But, curiously, a key to its survival seems to be a transformation in its meaning: In the 1800s, “à la mode” was typically applied to beef with wine sauce (not ice cream).

Two American cities claim to be the origin of à la mode as ice cream atop dessert: Duluth, Minnesota, and Cambridge, New York. The Associated Press obituary of a Cambridge concert pianist in 1936 credited him as the dish’s inventor and popularizer. But the Minnesota press soon responded with their own claim. Perhaps the linguistic wrangling kept the name around after others fell by the wayside. Or perhaps dessert with ice cream will always be in fashion.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook