How Iceland Beat the British in the Four Cod Wars

For decades, two island nations came to blows over fish.

In Icelandic, they were known as Þorskastríðin, “the cod strife,” or Landhelgisstríðin, “the wars for the territorial waters.” In English, they were simply “the Cod Wars.” Between the late 1940s and 1976, the two island nations of Iceland and the United Kingdom all but declared war—despite the fact that there were almost no casualties, and the former had no army.

In the frigid waters between these two nations, four confrontations took place between Great Britain, a world superpower, and Iceland, a microstate of just a few hundred thousand people. Each time, Iceland won. And it all happened because of cod—and the right to fish it. These were the Cod Wars.

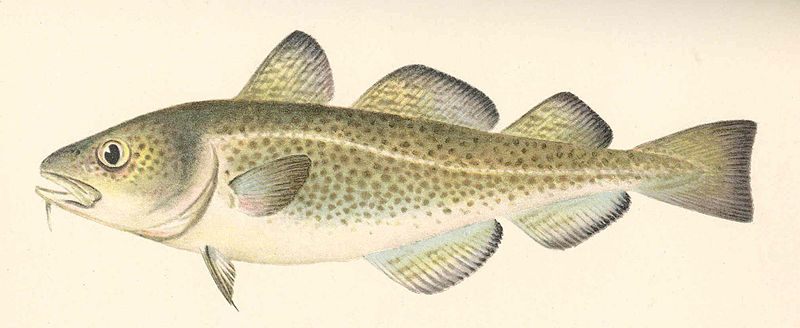

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a nation surrounded by hundreds of square miles of ocean on all sides relies heavily on fish. It has long been Iceland’s main food supply and primary export product. But of all fish, cod is the most important: a raison d’etre, a source of national pride to rival their soccer team, and a favorite thing to eat. Sometimes, it’s dried into a kind of fish jerky and smeared with butter. Sometimes, it’s salted (one of Iceland’s biggest exports). Sometimes, it’s simply the fish’s gellur (the fleshy triangular muscle behind and under the tongue) boiled or served in a gratin. It is Iceland’s very own watery white gold, and the country carefully guards its bounty.

But in the lead-up to the Second World War, Icelandic fishermen grew concerned about a preponderance of British ships in their waters, which affected how much cod they could catch themselves. Anxiety mounted until, in 1952, they announced new rules, limiting the Icelandic waters where British fishermen could trawl, and expanding Icelandic fishery zones from three to four nautical miles from the shore.

The United Kingdom, incensed by this swat from its tiny neighbor, retaliated by imposing a landing ban on Icelandic fish in British ports. It was a costly sanction—the U.K. was Iceland’s largest export market for fish. It backfired, however, when the USSR found homes for Iceland’s unsold fish. In the midst of its own Cold War, the U.S. followed suit, perhaps fearing greater Soviet influence, and encouraged its European allies to do the same. The sanctions thus minimized, Iceland could maintain their new limits. Eventually, in 1956, Great Britain capitulated the first Cod War, in the wake of a decision from the Organisation of European Economic Co-operation that sided with Iceland.

That might have been that, but in September 1958, Iceland expanded its national waters still further, from four nautical miles to 12, deep into waters that had previously belonged to no one. NATO, the Western military alliance, was up in arms, and Britain refused to cooperate. With the backing of virtually every western European country, Britain insisted they would continue to fish where they had before, under the protection of Royal Navy warships.

During the first Cod War, sometimes described as the prequel to the later three, Iceland had done little to enforce its ban: Its Coast Guard arrested only one British trawler. This time, however, skirmishes were frequent and shots were fired.

In one such altercation, in November 1958, the Icelandic gunboat V/s Þór fired warning shots at the British trawler Hackness. Eventually, the British navy ship HMS Russell intervened, and pointed out that the British ship was well outside the four-mile limit (that the British recognized as legitimate). Þór’s captain would not retreat, and ordered his men to man their guns and approach the wayward trawler. Russell, a comparable titan, made it clear that they would sink the boat if it shot the trawler. A brief stalemate followed, until the arrival of more British ships forced the Þór to back down.

By early 1961, clashes such as these made the situation more and more untenable. Diplomatic relations were worsening—Icelandic people protested the British and taunted the British ambassador when he visited the country—and Britain’s Royal Navy chaperones were proving expensive. With Iceland threatening to leave NATO, a compromise was drawn up: The United Kingdom would recognize Iceland’s 12-mile limit, with certain concessions in the first three years. The rest of the world, recognizing the risk of further conflict, imposed a new rule. Any further fights over cod between the two countries were to be sent directly to the International Court of Justice.

It was a prudent decision, but one that had little effect: Barely a decade later, in September 1972, the Icelandic government extended its fishing limits again, now to 50 miles. In the past, they’d been reluctant to assert themselves with military force. Now, however, they had a secret weapon, which they happily deployed. All seven of Iceland’s Coast Guard ships were armed with trawl wire cutters. “In reality,” writes Mark Kurlansky in Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, “the new weapon applied the old technology of minesweeping to fishing. One of the device’s four prongs would ensnare a trawl cable and cut it, letting loose a net worth $5,000 and whatever catch might be in it. A trawler without a trawl had nothing to do but go home.”

Once again, Western Europe opposed Iceland’s decision; once again, Iceland held firm, declaring that they were battling against imperialism and for their economic independence. “After the effectiveness of the trawl wire cutter was demonstrated,” Kurlansky writes, “the second Cod War denigrated into dodgem cars on the high seas.” Trawlers and Coast Guard vessels were ramming into each other, in attempts to prevent or incur trawl cable cutting. Britain’s NATO commitments made them unable, legally, to call on the Navy for support. Vessels were damaged, but, incredibly, no one was hurt.

It seems amazing from the outside, Kurlansky writes, that Iceland could be so hostile to its close neighbor and ally. But cod was worth major diplomatic tussling. “Unlike Britain, Iceland depended on fishing for its entire economy.” Cod alone had lifted the country into affluence and modernity. “Despite a history of warm feelings between the two nations and a close alliance, Iceland was not going to yield on its only resource.” Under pressure from NATO, Britain capitulated in late 1973. Iceland’s determination had carried it to victory yet again.

That might have been that, but global legal changes in 1975 provoked Iceland to act a final time. Despite the 50-mile limit, Icelandic fish stocks were under threat from overfishing more generally. A 200-mile limit was considered, and then adopted. British trawlers and fishermen within that limit began clashing with Icelandic gunboats, and the Royal Navy was brought in again. It was short, but messy, with 35 ramming incidents in six months. Iceland refused to negotiate, eventually severing diplomatic ties with Britain altogether despite repeated meetings between foreign and prime ministers.

Once again, NATO stepped in. Iceland was threatening to leave for good, and these “friendly” naval battles risked getting out of hand. For the fourth and final time, Iceland asserted itself, and the United Kingdom caved. The Cod Wars were over. There had been just two casualties: a British fisherman, from Grimsby, who had been hit by a hawser (towing cable), and an Icelandic engineer, who was accidentally electrocuted while repairing his hull.

The British economy may not have relied on cod as much as Iceland’s, but the effects were certainly felt. As Britain’s fisheries effectively closed, a depression settled over the country’s large northern fishing ports, such as Grimsby, Hull, and Fleetwood. Thousands of skilled fishermen, and those in related trades, including fish merchants and chip shop owners, lost their jobs. Meanwhile, Iceland’s 200-mile zone became the standard, curtailing foreign fishing all over the world.

All of this barely slowed the overfishing of cod, though. In 1998, the World Wildlife Foundation placed cod on the endangered species list, enacting limits on how much cod people could catch—no matter where in the world they were located. Iceland might have prevented foreign powers from fishing in its waters, but even a tiny country with a fighting spirit was no match for the natural and international limits now placed on its most delicious national treasure.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook