Almost Every Original Bob Ross Painting Lives in a Virginia Office Park

Now some of the iconic American painter’s work is headed to the Smithsonian.

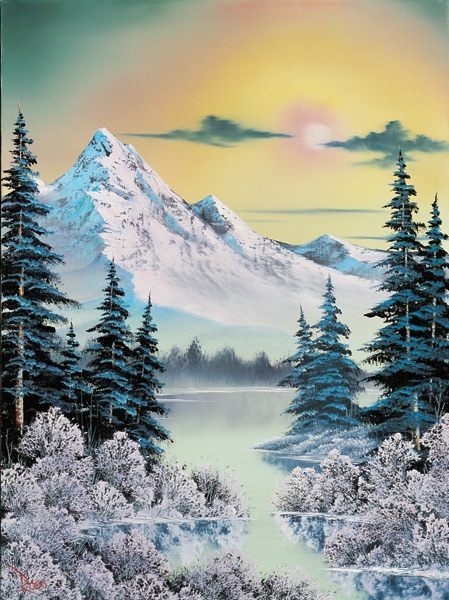

Somewhere off Route 50 in Herndon, Virginia, next to a LabCorp and across the street from a dentist’s office, there is a warehouse that houses almost every painting ever painted by one of the most recognizable painters in America: Bob Ross. They’re not on display, but are stacked carefully in numbered cardboard boxes; landscape upon landscape, snow-capped peak upon snow-capped peak, happy little tree upon happy little tree.

Ross’s instructional television show, The Joy of Painting, ran on PBS for 31 seasons, from 1983 to 1994, each containing 13 episodes, for which Ross would make three versions of the same painting—one as an initial reference, one that he painted on TV, and a last, more painstaking version to be included in his books. Over his PBS tenure, Ross crafted some 1,143 original paintings (there were sometimes guest hosts), according to a recent video from The New York Times. The majority of those landscapes—and they are all landscapes—are housed in the warehouses of Bob Ross Inc., the company that sells his signature how-to books, art supplies, and memorabilia. We’d wager there are enough mountains, lakes, and happy little trees to designate Bob Ross Inc. a national park.

Though Bob Ross Inc. operates out of Virginia—run by Ross’s longtime business partner Annette Kowalski—Ross himself was a Florida man. He was born in Daytona Beach in 1942, and grew up in Orlando. When Ross turned 18, he enlisted in the United States Air Force and was eventually stationed at a base near Fairbanks, Alaska. There, Ross saw snow and mountains for the first time—staples of the landscapes now stacked in heaps in Virginia.

A warehouse is not a gallery, so visitors aren’t encouraged. It’s a fully functional office, Sarah Strohl, the executive assistant of Bob Ross Inc. writes in an email. But many of Ross’s paintings pepper the walls, alongside larger-than-life photos of him holding a baby raccoon, one of his many treasured woodland creatures. “The paintings in the halls are paintings that have hung up in the Bob Ross Inc. offices since the ’90s,” Strohl says. “There are quite a few.”

As one might expect from his 30-minute-episode-friendly style, there is no one Ross that stands out as a magnum opus. Describe one and you might describe a dozen: a waterfall, a stand of trees, a small cabin overlooking a lake. But as a collection, the oeuvre is rather impressive, a testament to consistency, replicability, and dedication.

So when the Smithsonian National Museum of American History set out to acquire some of Ross’s work, they searched for an example that was representative, according to Eric Jentsch, curator and deputy chair of the division of culture and arts at the museum. Jentsch worked with Bob Ross Inc. to select four paintings. He briefly considered acquiring Shades of Gray, a striking grayscale painting Ross made upon request from a colorblind fan (season 2, episode 4), but opted for more quintessential examples of the painter’s typical themes and wet-on-wet style: the book version of Blue Ridge Falls (season 30, episode 13) and all three versions of On a Clear Day (season 14, episode 8).

“There are differences between the paintings, as each had a very particular purpose,” Jentsch says. “The basic concept is the same, but if you look closely, there are differences in the lakefront, there’s more detail.” Jentsch and the museum also acquired a variety of Ross-adjacent memorabilia, including a stepstool he turned into an easel, a palette, brushes he stored in an old ammunition box, fan letters, production notebooks, a Funko Pop figure, and bobbleheads. The Smithsonian has yet to set a date to display Ross’s work, but Jentsch says they hope to soon.

Ross, who died in 1995 of lymphoma, was less concerned with his physical legacy than he was with inspiring a generation of people to pick up a paintbrush. “He was not selling himself as an artist, but selling that other people could be artists as well,” Jentsch says. Fittingly, none of the paintings in Bob Ross Inc. are for sale. In fact, the notion never even occurred to the Kowalskis, according to The New York Times.

“Well, we show people that anybody can paint a picture that they’re proud of,” Ross told the Orlando Sentinel in 1990. “It may never hang in the Smithsonian, but it will certainly be something that they’ll hang in their home and be proud of. And that’s what it’s all about.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook