Why Medieval Monasteries Branded Their Books

The fiery marks were a way to keep track of tomes on the move.

When books hit the road, they don’t always make their way home again. Who among us doesn’t have some rogue volumes on our shelves, pilfered from libraries or “borrowed” and then absorbed? In the 15th and 16th centuries, when book printing was in its infancy, this problem of books gone missing was especially pronounced when the volumes in question were expressly designed to roam.

In particular, texts tagged along as missionaries fanned out to proselytize across the New World. When it came to converting indigenous people to Christianity, religious texts were a powerful weapon in missionaries’ arsenals, and psalms, confessions, and other liturgical texts—written in Spanish, Latin, and scores of indigenous languages—were printed in Europe and shipped across the ocean to New Spain. This land, encompassing present-day Mexico and other portions of Central and South America, was an epicenter of conversion efforts, and it soon became a hub for the printed word, too.

It’s easy to imagine how books could become casualties of a life that was itinerant by design. “Missionaries’ whole mission was to go out and constantly be on the move, and the books were, as well,” says Melissa Moreton, an instructor at the Center for the Book at the University of Iowa. Before they did, monasteries and convents often made a bold claim to ownership. With a scalding tool, they seared distinctive marks onto the pages.

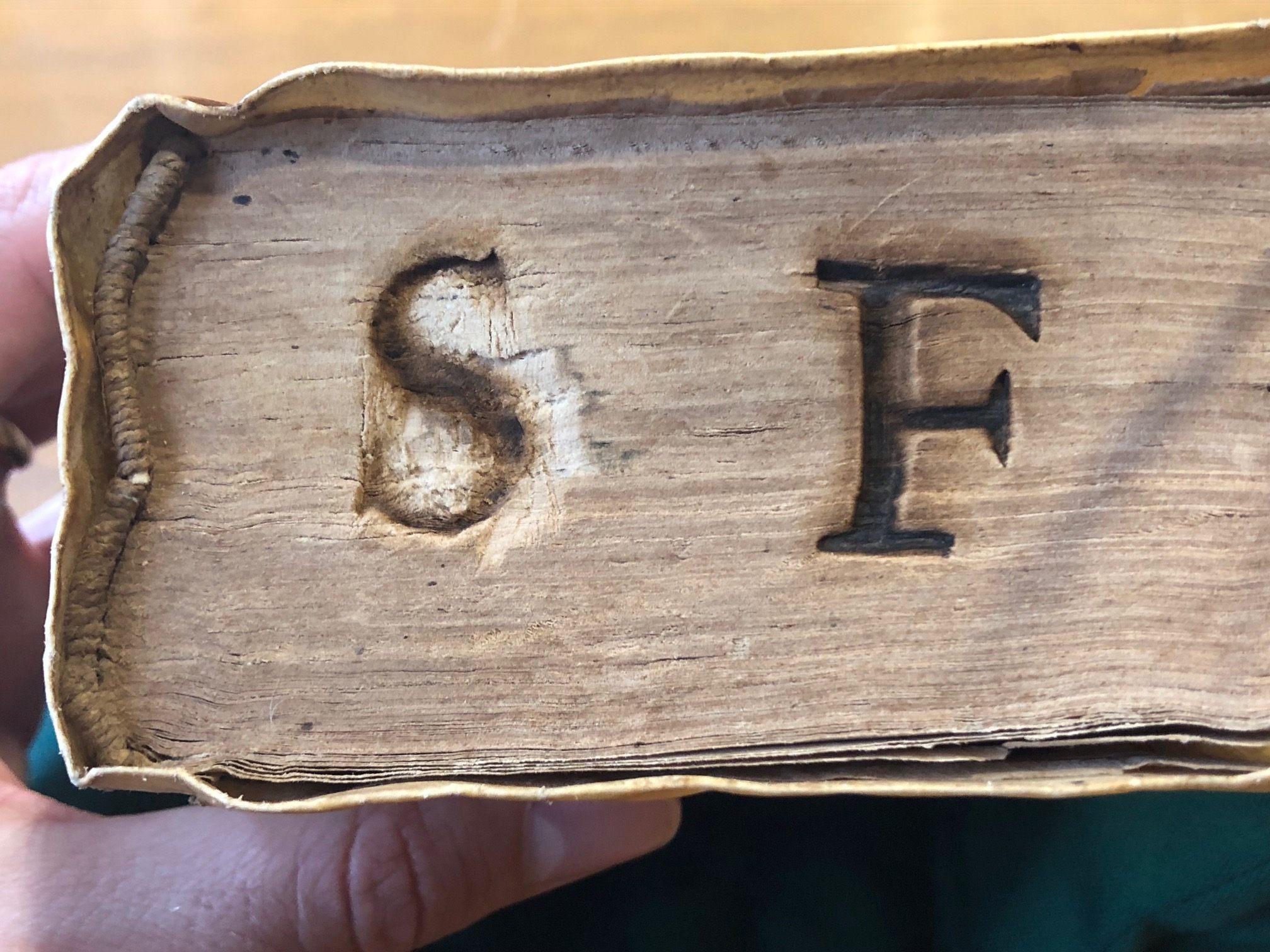

These marcas de fuego were both insurance and warning, “marking them in case someone would try to steal it from the library or convent,” says Analú López, the Ayer Indigenous Studies Librarian-in-Residence at Chicago’s Newberry library. Each order had its own symbol, which drew upon the group’s iconography. The marks made by Dominicans contain a cross, while Augustinians’ include a heart pierced by arrows, and Franciscans’ feature two crossed arms, signifying the spiritual fellowship between St. Francis and Christ. And within a given order, brands varied further from place to place.

In some respects, Moreton says, the practice was related to a longstanding European tradition. For hundreds of years, manuscripts had carried inscriptions that variously browbeat and beseeched readers. One text might bear a curse said to befall anyone who did wrong by the volume; another would simply ask nicely for its safe return. In a New World twist, fire brands did one better: They were on the pages, not the binding—which could easily have been removed—and they were deep. One Franciscan book, which Moreton studied during a recent fellowship at the Newberry, is branded so deeply that she suspects that the flames may have caught on the pages. Someone “kind of did a hack job to saw away at the burned, charred area to get F to look like an F again,” she says. “Otherwise, it was just a black blob of charred paper.”

Stylistically and procedurally, the process evoked cattle branding, and that reveals the esteem with which missionaries held the books, says Will Hansen, director of reader services and curator of Americana at the Newberry. “Marking a book the same way you would an extremely valuable piece of property—livestock—shows how much value you place on it because you don’t want to lose it.”

As proof of where the books were kept, the marks also illustrate the squabbles and ruptures that dominated theological conversations of the day. The Newberry’s collection includes a 1502 text by a Dominican author that debates whether or not the Virgin Mary had herself been the fruit of an immaculate conception.

Contemporary readers can also mine these texts for information about existing indigenous belief systems, “but you have to read across the grain,” says Hansen. The texts were created with particular aims in mind, catering primarily to indigenous people in the course of being converted (or to the priests who had arrived to foist their own belief system upon them).

With colleagues at Biblioteca Lafragua and Biblioteca Franciscana in Puebla, Mexico, Mercedes Salomón Salazar is cataloging hundreds of the marks on an online database. Even as this trove grows, there are many more questions to answer. Fire-branded books are “this area of book history that has yet to be fully investigated,” Moreton says. Who was branding them, and where were they licked with fire—at the printers’ or at the convent? Was this exclusively a New World practice? And to what extent is it possible to use the brand to reconstruct a book’s journey from one pair of hands to another?

Sometimes, Moreton says, a book easily gives up its secrets as you flip the pages. “If you get lucky, you have a juicy one with lots of notes,” she says—perhaps even readers or owners who introduce themselves on the inside cover, and carry a consistent handwriting style throughout their annotations. If contemporary sleuths know where to look, “the books are talking to us today,” Moreton says. Fire brands are one way that these texts can narrate their lives, and the systems of power and oppression that they traveled within.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook