The Very Proper Reason the British Library Has a Vulgar Dictionary

You can learn a lot from slang.

A “dictionary of the vulgar tongue” may sound like some kind of prank gift, something you pick up as a means of upping the ante on your name-calling or adding some spice to your conversations for all occasions. But you won’t find this dictionary at Spencer’s Gifts. It’s tucked away at the British Library in London, shelved and looking prim and proper in its original 1785 binding.

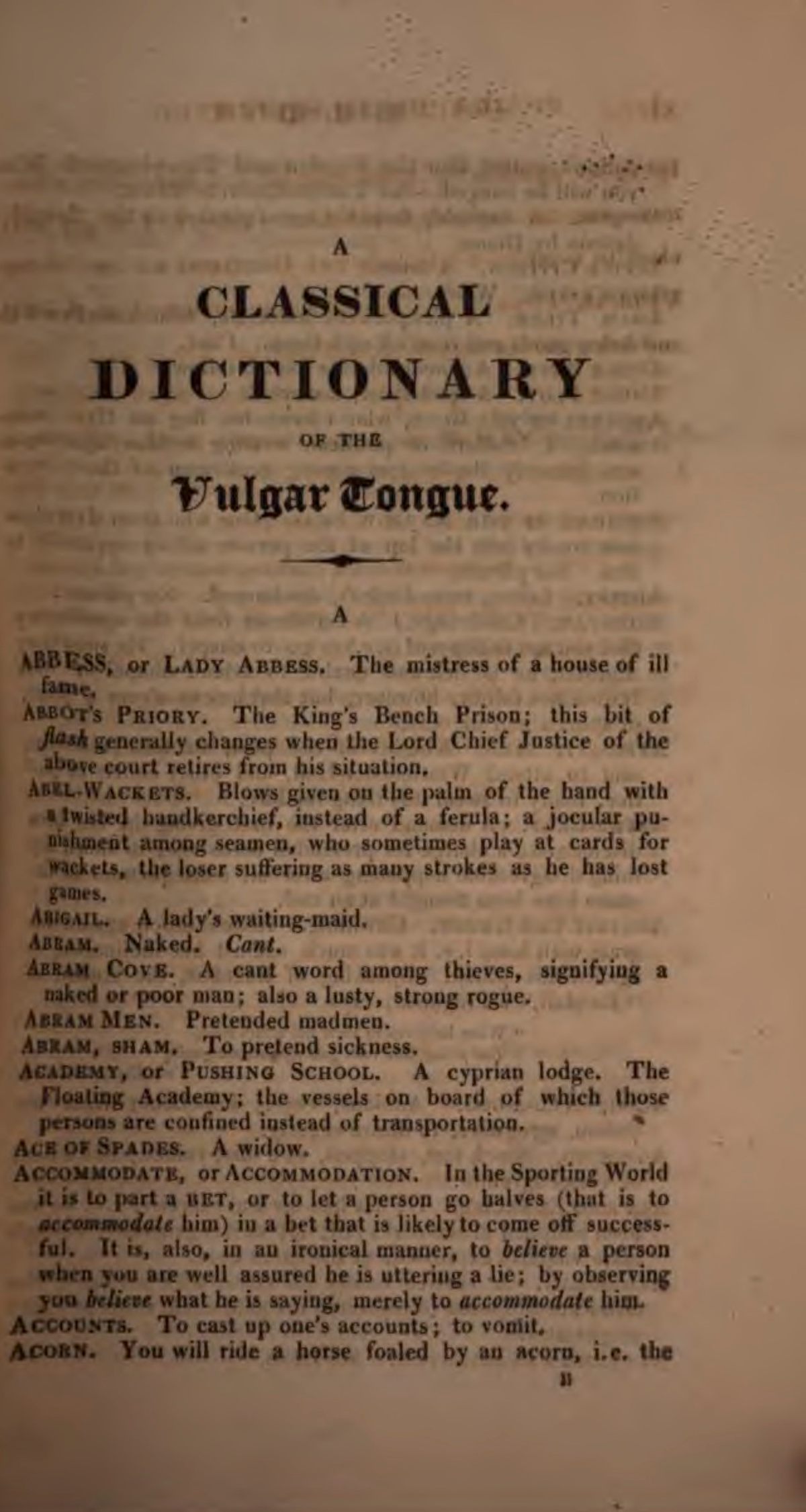

With aged, off-white pages and an unassuming cover, A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, written by Francis Grose, looks a lot like another noted 18th-century dictionary—Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language. The only thing differentiating these two is their focus: the English language versus the “vulgar tongue.”

Today, one sounds a bit haughty in scope and the other sounds a bit more fun, but the word “vulgar” didn’t have the same meaning in Grose’s time that it does now. It simply referred to the language that commonfolk used in everyday life—yes, including some swear words—as opposed to the proper English that Johnson had pursued.

There was an audience for these vulgarities: Grose’s dictionary sold quite well following its publication in 1785, according to lexicographer Jesse Sheidlower. So well, in fact, that it required a second printing just three years later in 1788, and then another five years after Grose’s death in 1796. Today, “it’s one of the more important slang books ever published,” says lexicographer Jesse Sheidlower, an adjunct assistant professor at Columbia University. “Johnson made a specific effort to keep out this kind of language.”

Grose—a poet and a military man—enjoyed the seedier parts of London, the late-night revelry where Johnson’s proper tongue wasn’t exactly adhered to, nor was it even widely understood.

The entries in Grose’s dictionary run the gamut from words and phrases common to laborers, military personnel, and bar frequenters to cant—the jargony language of criminals. Among the pages are such listings such as “cheeser,” another word for a fart; an “Admiral of the narrow seas,” someone who drunkenly vomits into the lap of the person sitting opposite him; and “to dance upon nothing,” meaning “to be hanged.”

There are also numerous entries that link Grose back to his military days, including “camp candlestick,” (a bayonet) and “caterpillar” (a slang for soldier). And there is plenty of shade. For instance, “kittle pitchering,” where one frequently interrupts a teller of long stories in an effort to curb their long-windedness and “duke of limbs,” which simply means a tall, awkward, ill-made fellow.

But this isn’t just a collection of fun phraseology, explains Sheidlower. It’s a window into a crossroads of language at the heart of 18th-century Britain. Terms used in various underground criminal enterprises—like “bean feakers,” or bill counterfeiters—intermingle with simple words used among commonfolk like “lobkin,” which is just another word for a house or home. (Some of the words and phrases included live on into the modern vernacular with their centuries-old meaning, such as “to screw” and “to kick the bucket.”)

And the “pop culture” references to late 18th century-England, such as specific jabs at societies or people in positions of power or influence, are also revealing. For instance, Grose takes a jab at Jesuits with his entry “to box the Jesuit,” which is to masturbate, something that Grose adds, “is much practised by the reverend fathers of that society.”

“It’s important that we study slang because it’s part of the world,” Sheidlower says. “It’s not acceptable to not like people because of how they speak.” Slang is all about fitting in, knowing how specific groups intercommunicate, and through the study of such dynamics, we can better understand how those groups operate in society, what values they hold, and more, rather than letting preconceived notions inaccurately define them.

Grose and his dictionary gave the world a peek inside various groups in danger of having their cultures steamrolled and made the language of commoners as worthy of study as that of aristocrats. You too can bury your nose in the pages of the same late-night revelry that Grose lived and documented: This vulgar tome has been digitized so read away, you jemmy fellow. (That means you’re clever.)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook