In Istanbul, Drinking Coffee in Public Was Once Punishable by Death

Rulers throughout Europe and the Middle East once tried to ban the black brew.

In 1633, the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV cracked down on a practice he believed was provoking social decay and disunity in his capital of Istanbul. The risk of disorder associated with this practice were so dire, he apparently thought, that he declared transgressors should be immediately put to death. By some accounts, Murad IV stalked the streets of Istanbul in disguise, whipping out a 100-pound broadsword to decapitate whomever he found engaged in this illicit activity.

So what did Murad IV find so objectionable? Public coffee consumption.

Odd though it may sound, Murad IV was neither the first nor last person to crack down on coffee drinking; he was just arguably the most brutal and successful in his efforts. Between the early 16th and late 18th centuries, a host of religious influencers and secular leaders, many but hardly all in the Ottoman Empire, took a crack at suppressing the black brew.

Few of them did so because they thought coffee’s mild mind-altering effects meant it was an objectionable narcotic (a common assumption). Instead most, including Murad IV, seemed to believe that coffee shops could erode social norms, encourage dangerous thoughts or speech, and even directly foment seditious plots. In the modern world, where Starbucks is ubiquitous and innocuous, this sounds absurd. But Murad IV did have reason to fear coffee culture.

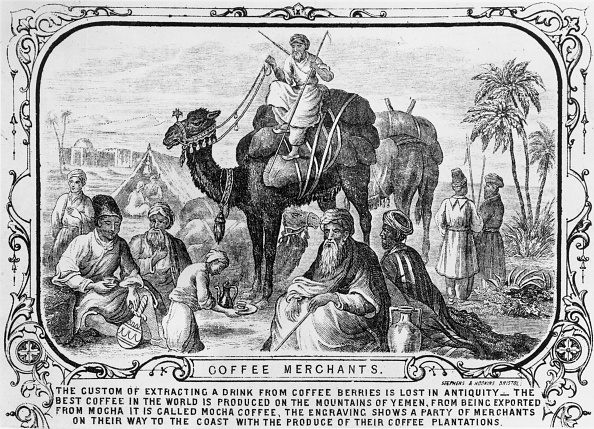

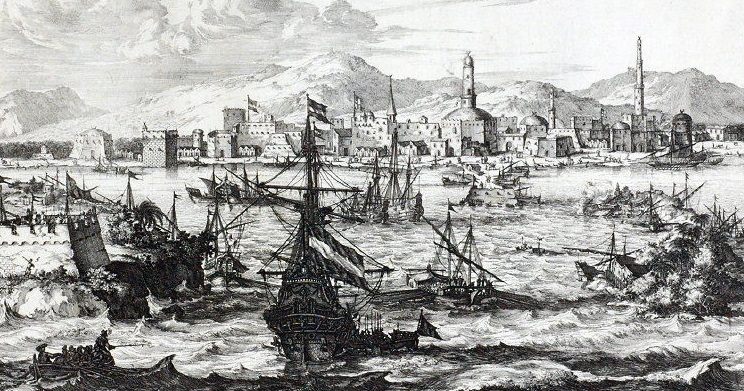

These crackdowns touched off in the 16th century because that’s when coffee reached much of the world. Coffee beans were likely known and used for centuries beforehand in Ethiopia, their point of origin. But the first clear historical evidence of grinding coffee beans and brewing them into a cup of joe dates—as the historian Ralph Hattox established in his definitive tome Coffee and Coffeehouses—to 15th century Yemen. There, local Sufi Muslim orders used the brew in mystical ceremonies, whether as a social act to foster brotherhood, a narcotic to produce spiritual intoxication, or a pragmatic concentration booster. The drink soon spread up the Red Sea, reaching Istanbul in the early 1500s and Christian Europe over the following century.

In response, reactionaries cited religious reasons to outlaw coffee. “There’s always an undercurrent of” conservative Muslims “who think that any innovation … that is distinct from the time of the prophet Muhammad should be quashed,” says Ottoman social historian Madeline Zilfi. (Reactionary tendencies are not unique to Islam; later, in Europe, religious leaders asked the Pope to ban coffee as a satanic novelty.) Justifications included that coffee intoxicated drinkers (forbidden), that it was bad for the human body (forbidden), and that roasting made it the equivalent of charcoal (forbidden for consumption). Other religious figures charged (maybe legitimately, maybe dubiously) that coffeehouses were natural magnets for licentious behaviors such as gambling, prostitution, and drug usage. Others just thought the fact that it was new was reason enough to condemn it.

But reactionary religious arguments cannot explain most of the coffee crackdowns in the Ottoman Empire. As Hattox notes, the religious establishment was hardly uniform in its opposition to coffee. Bostanzade Mehmet Efendi, the highest ranking cleric in the Ottoman world in the 1590s, even issued a poetic defense of coffee.

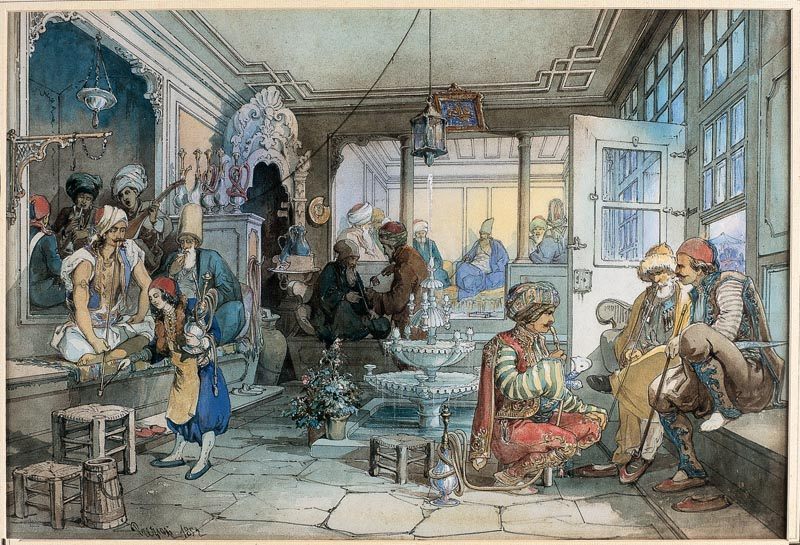

More often, secular authorities opposed coffee for political reasons. Before coffeehouses, Zilfi points out, there weren’t many spaces in the Ottoman Empire for people to gather, especially across social lines, and talk secular matters. Mosques offered a gathering place, but rarely accommodated long, worldly chit chat. Taverns weren’t for good Muslims, and patrons usually got ripped with people they knew, had fun, then passed out.

Coffeehouses, though, were considered acceptable for Muslims. They were cheap and lacked social restrictions, so they were accessible to everyone. The way they made coffee—slowly brewed in a special pot for almost 20 minutes, then served in a cup filled to the brim, so bitter and scalding hot that it could only be consumed in tiny sips—encouraged patrons to sit, watch whatever entertainment came through, and talk. They were a new social space that encouraged class mixing and energetic conversation about cities and governments.

That spooked the bajeezus out of elites concerned with ossifying social order in the name of stability. Which often meant their own elevated place in Ottoman society. They made it clear that they didn’t like coffee shops’ public gatherings, or even the fact that the poor could suddenly patronize art, once the sole pursuit of the upper class. Authors such as 17th-century Ottoman scholar Kâtip Çelebi, a state bureaucrat from a well-to-do family, disparaged cafés as places that “diverted the people from their employments, and [where] working for one’s living fell into disfavor. Moreover, the people, from prince to beggar, amused themselves with knifing one another.”

The first recorded coffee crackdown occurred in Mecca in 1511, when Kha‘ir Beg al-Mi‘mar, a prominent secular official in a pre-Ottoman regime, caught men drinking coffee outside of a mosque and thought they looked suspicious. The details of the crackdown are disputed, but he used religious justifications to order an end to all coffee sales and consumption. Later coffee crackdowns occured in Mecca (again), Cairo (multiple times), and Istanbul and other Ottoman areas.

These early suppression efforts were motivated by politics, religion, or a mix of the two, but they were sporadic and short-lived. The 1511 Mecca crackdown, for instance, ended within weeks, when a higher political authority told al-Ma‘mir to continue suppressing questionable meetings but let people have their coffee already. The Ottomans were reportedly sporadic in their bans as well; coffee was just too popular and profitable. By the end of the 16th century, the Ottoman court had an official coffee maker, hundreds of coffeehouses dotted Istanbul, and the government officially declared coffee and coffeehouses writ large licit.

Murad IV, though, had particular reason to hate coffee culture. In his childhood, explains Ottoman political historian Baki Tezcan, his brother Osman II was deposed and brutally murdered by the janissaries, a military group that had grown increasingly autonomous and discontented. A year later, they deposed his uncle. Thereafter, they installed Murad IV as a child ruler. He lived in fear of janissary rebellions—and suffered several minor uprisings in his early reign. During one rebellion, says Tezcan, “they hung people close to him. One was his close personal companion, Musa … somebody with whom he used to drink. He might even have been an erotic male friend.”

This, says Tezcan, “left Murad IV really angry. He gradually, slowly took power into his own hands in a very draconian manner. That really pushed him to become the person remembered as Murad IV,” a notoriously power- and order-obsessed absolutist, quick to resort to lethal force.

Murad IV knew that demobilized or under-employed janissaries frequented coffee shops—and used them to plot coups. Some coffeehouses eventually used janissary troupe insignia as their signage. Murad IV was also likely aware, argues Ottoman historian Emingül Karababa, that a conservative religious movement, which opposed Sufis and social innovations connected to them, including coffeehouses, was rising in his empire. “He did not want to have tension and uprisings in the society under his rule,” as he sought to wrest control from the janissaries, argues Karababa. So it was doubly in his interest to oppose coffeehouses.

The Sultan’s decision to impose the death penalty for all public coffee drinking, though, was all about his own cruel streak. Murad IV also imposed the death penalty on public tobacco and opium consumption and closed taverns, other sources of supposed vice and disorder. He killed soldiers for minor infractions, and in the worst stories about him, he flew into blind, middle-of-the-night rages and ran into the streets half naked to murder anyone he came across. Given all the grim stories, Tezcan suspects there could be a grain of truth to tales of him stalking Istanbul in disguise with a broadsword. After all, chroniclers of the time wrote approvingly of his brutality—these tales weren’t meant as slander.

Murad IV never banned coffee wholesale. He just went after coffeehouses, and only in the capital, where a janissary uprising would pose the most risk to his rule. Murad IV kept on drinking coffee—and liquor—himself, and tolerated consumption so long as it occurred in socially homogeneous households.

The Sultan’s successors continued his policies, to greater or lesser degrees. By the mid-1650s, over a decade after Murad IV’s death, Çelebi wrote that Istanbul’s coffeehouses were still “as desolate as the heart of the ignorant.” Although by that time a first coffee drinking offense resulted in just a beating; only a second offense would get a coffee drinker sewn into a bag and thrown into the Bosporus. But coffee culture survived in the background, and popped right back under more lax or unconcerned rulers later in the century.

Yet even after seeing the resilience of coffee culture at home, and likely knowing about the failure of 17th-century coffeehouse bans in Europe (documented by coffee historian Markman Ellis), Ottoman sultans sporadically issued and abandoned new bans well into the 18th century. This may seem quixotic, but, Zilfi points out, the goal wasn’t really to eliminate the drink, or even coffeehouses. Crackdowns were likely considered successful, she notes, as long as they made it harder for the janissaries or other dissidents to mobilize, and unnecessary if a ruler felt secure in his power.

By the late 18th century, though, more secular meeting places had emerged, and dissident groups were more entrenched. Shuttering coffeehouses was no longer a go-to dissent crusher, so the bans stopped—although rulers still posted spies in them to monitor anti-regime chatter, a practice some autocrats maintain to this day.

Murad IV, then, was an exceptionally brutal man. But he was not some insane reactionary. Instead, he and his peers speak to the power that a new commodity, such as coffee or tobacco, can have: Something as simple as creating a new culinary venue can wash away old mores and open up new spaces for engagement and thought. They speak to the horror and reactionary politics such innovations, such critical thoughts and challenges to accepted norms, can provoke.

Coffee culture won out against religious and political conservatism, though, and now we live in the world of Starbucks. And won’t it be surprising to see which social innovations stirring up apocalyptic prophecies today become as ubiquitous and uninteresting as the green mermaid logo a century or two down the road?

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook