Ancient Drinking Games Ended With Wine Stains and Stabbing

Inebriated play, from ancient Rome to Tang Dynasty China.

This article is adapted from the October 16, 2021, edition of Gastro Obscura’s Favorite Things newsletter. You can sign up here.

Last week, the Gastro Obscura team assembled via Zoom for an ancient tradition. Each of us reclined on our couch, took aim with a large spoon full of liquid, and hurled it at a small target positioned atop a teetering tower. We were playing an adapted form of kottabos, a drinking game that dates back to ancient Greece.

Traditionally, the game involved flinging wine at a disc using a small saucer known as a kylix. But since we didn’t have ancient equipment and didn’t want wine-splattered rooms, we used large spoons, water, and a small cup placed atop a Jenga-like tower of cups and containers. Our takeaways: It’s harder than it looks, and you might want to wear a poncho. Also, Gastro Obscura Editor Alex Mayyasi is a kottabos master.

This week, we journey from the Tang Dynasty to Enlightenment Europe on a time-traveling tour through some of the most interesting drinking games across history. Although such competitions are now relegated to the realm of drunken frat boys, everyone from ancient philosophers to royalty have engaged in inebriated play.

Drinking by Automaton

If you ever played spin the bottle and thought, “This is great, but what if we added a robot?” allow me to present Diana and the Stag. At first glance, the figure appears to be simply a silver objet d’ art that depicts the goddess astride a deer. But it’s actually an example of an automaton that was used in drinking games in 17th-century European royal courts.

After one player wound up the machine, it slowly moved around the table, until randomly stopping before someone. That person, naturally, had to drink: The stag’s head cracked open to reveal a small drinking vessel. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art has Diana and the Stag on display, but you can see other automata in European museums.

Cards, With a Side of Sadistic Power Trips

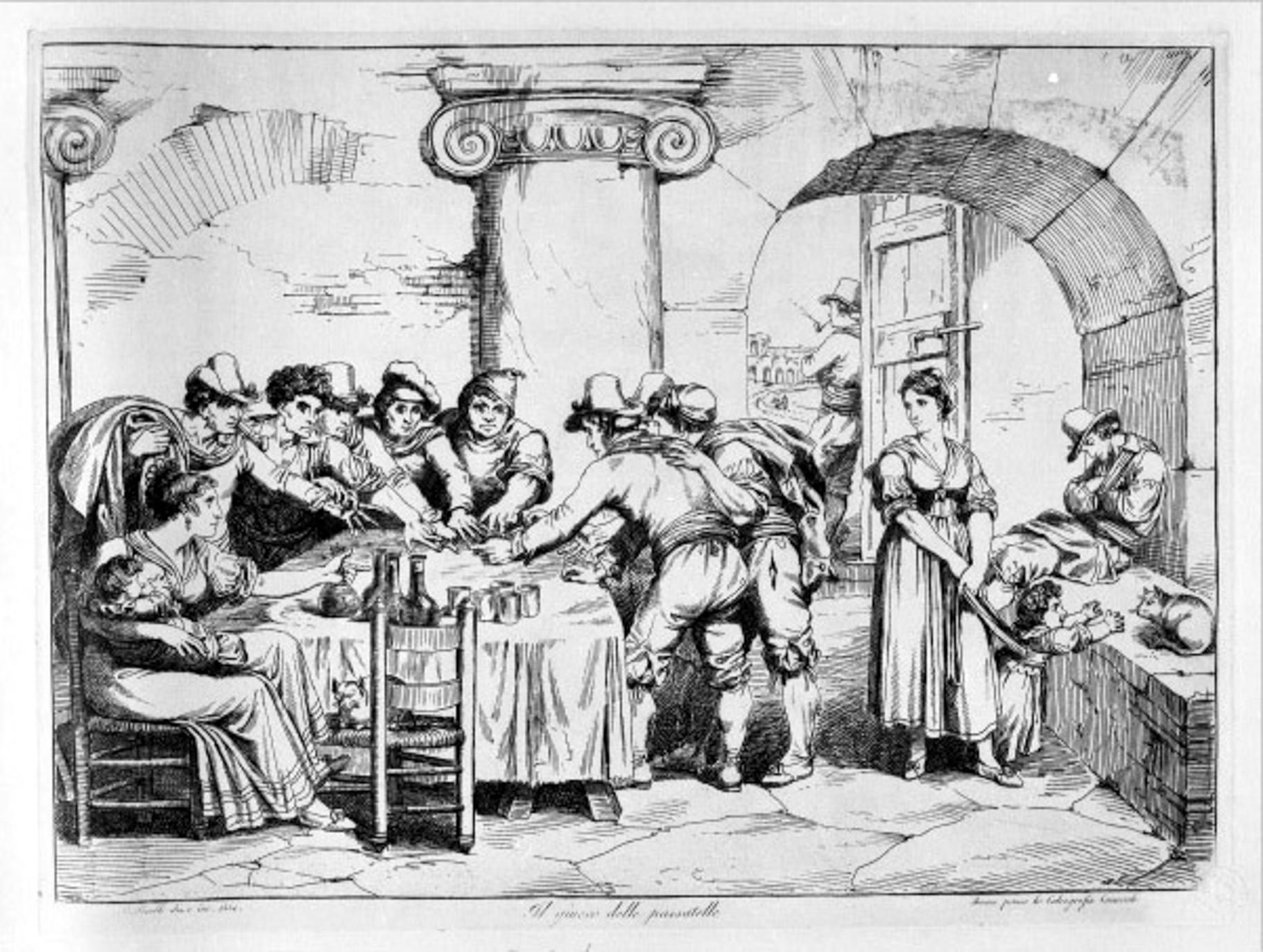

You know a game is hardcore when it comes with a warning about possible stabbings. Dating back to ancient Rome and played by everyone from the lowliest pleb to Cicero, passatella begins with each player receiving four cards (from a Neapolitan deck). Whichever two players have the highest card values get designated the Boss and Underboss.

Here’s where it gets interesting: While everyone has to chip in for each round of drinks, the two bosses are able to dispense and deny drinks, often through insult-laden speeches. But anyone suffering through a dry spell has the opportunity for revenge in the next round, when new bosses get crowned.

By the Middle Ages, the game became downright violent, often ending with brandished knives. While this might not sound like fun to everyone, the game is still played in taverns in Southern Italy.

Drunk and Orderly

Historic Chinese drinking games known as jiuling began as a means to maintain order at parties. Instead of cards, players drew lots from a silver container. Each lot came inscribed with instructions, ordering different people at the table—ranging from the youngest to the most talkative to the highest-ranking official—to imbibe.

Like passatella, the game had several officiants who ruled over players; however, their job was to actually ensure things didn’t get out of hand. Players who proved too rowdy or rude were given penalties. This makes sense, until you realize that those penalties were usually just more drinks.

In China’s Golden Age, Charles Benn tells the story of a ninth-century drinker who committed several party fouls and was sentenced to 12 “penalty cups.” When he couldn’t drink any more, he left the game. This final act was yet one more infraction—“the fraternity of the goblet had little sympathy for such cowardice”—which would result in not being invited to future games.

Swinging Wager Cups

Many drinking games are tests of aim or balance—both of which become diminished after several glasses of wine. Dating back to 16th-century Germany, wager cups were a test of the latter.

The two-sided drinking vessels came in the shape of a woman whose skirt formed one large cup and who held another small cup above her head. This tinier cup could swivel back and forth, allowing it to remain upright as the drinker attempted to sip from the skirt. At weddings, brides and grooms were challenged to drink from each cup without spilling a drop.

Non-nuptial wager cups were also popular as drinking games, sometimes featuring a man instead of the skirted maiden.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook