Ann Haviland, Forgotten Mastermind of the Signature Scent

Meet the woman dubbed the “poetess of perfume” in 1917.

Decades before beauty pioneers Estée Lauder and Elizabeth Arden released fragrances for their cosmetics brands, even before Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel put her name on the now-iconic No. 5 in 1921, Ann Haviland was a celebrated American perfumer with a creative approach to making and selling fragrance. Her motto was “A perfume for every woman and to every woman her own perfume”—and although her name is now largely forgotten, her career deserves a look back.

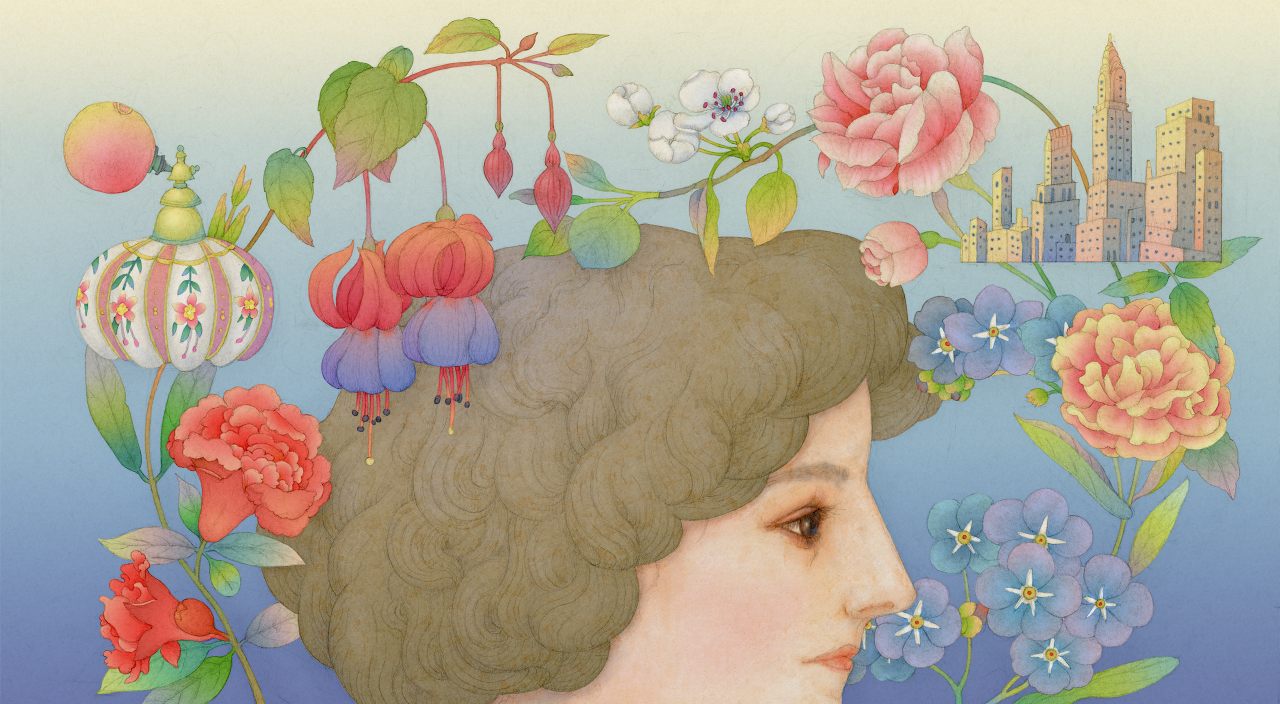

Haviland was born circa 1878 in Millington, Maryland and grew up on a family estate with a conservatory and extensive flower gardens, where she learned to identify different varieties of rose by smell. She was educated in Philadelphia and married a cousin who was a pharmacist by trade. After her husband’s death, she started her own business as a perfumer around 1912. Although sources are vague as to the exact dates, she received training from prominent French perfumer Eugene Charabot in Paris in order to hone her natural abilities. Before long, her sensitive sense of smell had earned her the nickname of “the woman with the most wonderful nose in the world.”

When Haviland went into business in New York just before the First World War, the American luxury perfume market was dominated by French brands like Coty, Guerlain, and Houbigant. Most American-made fragrances were modestly priced scents manufactured by large toiletries companies like Colgate or Solon Palmer and sold at drugstores. Even when smaller American companies produced perfumes, they adhered to an established repertoire of scents that varied little from brand to brand. With the exception of New York-based Richard Hudnut, who offered elegantly packaged fragrances and cosmetics in direct competition with imported French products, American perfumeries tended to emphasize affordability and convenience rather than luxury or uniqueness.

Haviland’s products, however, were upscale, customized, and based on her own “psychology of scent,” as one writer described it. Haviland made her mark by offering one-of-a-kind perfumes, consulting with individual clients to identify the “notes” that best enhanced their personalities. Some of her early publicity resulted from associations with famous actresses like Alla Nazimova and Theda Bara. Bara, who dubbed Haviland “the poetess of perfume” in 1917, mentioned her customized Haviland fragrance in several interviews. After meeting Bara, who was at the height of her fame as “The Vamp” and was about to star in Cleopatra, Haviland decided to convey Bara’s dual nature through scent: she evoked what she called Bara’s mysterious, “snake-like charm” with Middle Eastern resins and woods and expressed the actress’s gentler, private side with pomegranate blossoms.

Haviland also gained attention as an “artistic perfumer” through her experiments with ambient fragrance. In 1914 the railroad tycoon James “Diamond Jim” Brady commissioned a unique home fragrance from Haviland. Upon visiting his Manhattan mansion, Haviland decided to create different fragrances for eight rooms, matching her compositions to the spaces’ color schemes and decor styles; sachets discreetly placed under rugs and in chandeliers gave off a subtle but long-lasting effect. Haviland also ventured onto Broadway: in 1915 she scented a production of the early Jerome Kern musical Nobody Home, blending a fragrance that would be wafted throughout the theater during performances.

Haviland’s customers weren’t all screen stars and robber barons: her studio in midtown Manhattan was open by appointment to anyone who wished to consult with the “perfume psychologist,” as she was known. Although her bespoke fragrances were costly (prices ran as high as $90 per ounce by the early 1920s), stylish New Yorkers sought her out enthusiastically. Clients could also purchase matching bath products, or perfumed oil formulated to be dabbed on fur coats; a bride could have her entire trousseau infused with a signature scent. Haviland even sold a scented paste that was applied to the tips of cigarettes. “This does not spoil the taste of your Camel,” a reporter for The New Yorker wrote, “but manages to scent the room with amber instead of the fumes of stale tobacco.”

Women who couldn’t afford a personalized scent could still learn about Haviland’s philosophy of “perfume to fit the soul,” as a writer for the Hartford Courant described it: Haviland was frequently interviewed for newspapers and magazines (and the occasional radio program). “When a woman comes to me,” she explained, “I study first of all her personality and then her type of beauty. I go into my laboratory and fix up a perfume that is as distinctive to her as her own self.” Like today’s perfume experts and beauty journalists, she gave advice for choosing a signature fragrance, taking into account everything from hair color and physical type to personality traits and occupation, from the “domestically inclined girl” to the “intellectual type.” For example, she suggested, “The flapper, really innocent, although desiring beyond all else to impress the world with her sophistication, should use a spice such as carnation or phlox combined with mignonette or heliotrope—if she is a brunet.” She also spoke about her choice of high-quality natural ingredients: she preferred floral essences imported from France and spices and herbs from the Middle East and South Asia, and she criticized most American perfumes for being too synthetic.

In a 1915 interview with the New-York Tribune, Haviland even made analogies between perfumery and other media, mentioning her feeling of kinship with couturier Paul Poiret and the avant-garde Futurist painters. “Perfuming follows futurist art,” she said, “and by that I mean the color side of futurist art. I am perfectly mad about color, and as I think color harmony I think perfume harmony. Am I making myself clear?” For Haviland, perfume transcended its status as a hygiene product or a mere frivolity: it could be an intimate artistic collaboration between perfumer and client. “Perfume is an art as subtle as music, as intangible as the quality that reveals the soul in certain portraits; as powerful to express the inner spirit as the notes of the human voice,” she remarked in a 1914 interview with Harper’s Bazar, as it was then known.

By the 1940s, however, the Ann Haviland brand was represented by more mainstream floral fragrances at department stores across the United States. Haviland was no longer known as a purveyor of “personality in a bottle,” as she had been two decades earlier. The fragrance field was increasingly competitive, crowded with French perfume houses and an increasing number of American companies, some of them helmed by other women. Cosmetics moguls Elizabeth Arden, Helena Rubinstein, and Estée Lauder began offering branded fragrances, and designers like Hattie Carnegie and Nettie Rosenstein were licensing perfumes to accompany their fashions. Meanwhile, mass-market brands like Revlon and direct-sales companies like Avon (formerly California Perfume Company) captured an ever-growing market share.

At the time of her death in 1958, Haviland was retired and living in Westport, Connecticut.Obituaries mentioned her work as a perfumer, although they failed to note how groundbreaking her accomplishments were. It’s unfortunate that none of them quoted articles like Harper’s Bazar’s profile from 1917: “Ann Haviland is an artist. She is the only woman in this country who is striving to lift the compounding of a perfume out of the realm of the commercial. The ingredients in a perfume she chooses as the artist selects his pigments and through them endeavours to express that intangible something which is everything—personality.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook