How Alarming Is It That Islands Are Just Disappearing?

Very, but the story of sea level rise is a lot more complicated than that.

Every so often—more often lately—comes news of islands just up and disappearing. Eight in Micronesia. Five in the Solomon Islands. One off the coast of Hokkaido, Japan. Yet there’s also been a crop of studies and researchers, led by coastal geomorphologist Paul Kench from Simon Fraser University, saying that island nations such as Tuvalu (long a poster child for the existential threat of sea level rise) not only aren’t disappearing—they’re actually growing. So how do we make sense of this? Are the low-lying islands we know today doomed? Or are we seeing some other process at work? The answer is that a million complicated things are happening all at once, and it provides a window into how hard it is to talk about what’s currently happening to the planet.

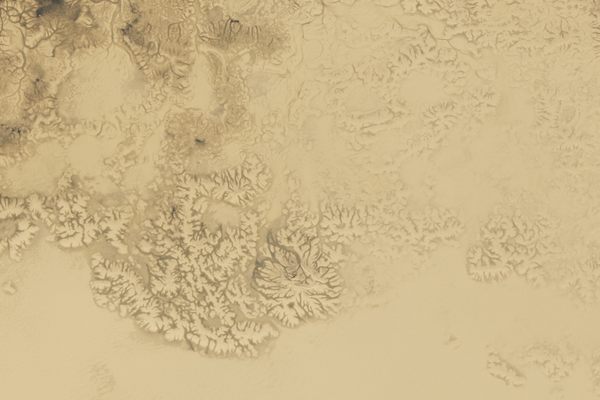

When we speak of islands that can disappear beneath the waves, it’s almost exclusively the small, low-lying ones, which form in a couple of different ways. Some are volcanic in origin, created when an undersea volcano bursts up through the sea surface, forming a small island. Sometimes those islands can stick around, but often, especially in the South Pacific, they don’t. But while they’re above the surface, coral polyps colonize the slopes of these new islands—they like to be fairly near, but not too near, the surface—and build up in a ring shape around the cone of the volcano. If the volcanic landmass gradually erodes or subsides, what’s left is just the coral and the material it accumulates, usually in a ring shape known as an atoll, with a shallow lagoon in the middle. In the case of bigger islands, when more geological activity forces them up higher, there may be a more substantial flat area rather than a lagoon.

Most other low-lying islands are barrier islands, which are generally created when tides, waves, and wind push sand and sediment to one specific place, impacted by the shape and profile of the adjacent coast. Unlike atolls, which are only found in the tropics, where shallow-water corals thrive, barrier islands can be found pretty much anywhere.

Coastal encroachment can impact larger, higher islands, but disappearing? Only the low-lyers are at risk of that. Despite the fact that barrier islands are everywhere, from the Canadian Maritimes to the Frisian Islands in northwestern Europe to all up and down the American East Coast to … well, everywhere, they’re not usually the focus of disappearing-island concerns. Barrier islands can come and go, but the islands that get the bulk of the attention for disappearing are atolls in the South Pacific. And there’s a reason for that.

“The Pacific as a basin just has a lot more variability,” says Andrew Ashton, a coastal geomorphologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. El Niño and La Niña oscillations, in which cycles of warm and cold water change the climate, hit the South Pacific hard, especially in the form of storms such as tropical cyclones. Many of the region’s islands—and it is a massive region—lie in what’s called the South Pacific Convergence Zone. A convergence zone is where winds from two separate regions, usually one cold and one hot, collide, causing a lot of rain and wind. (There’s a little one over Seattle.) The one in the South Pacific is huge and powerful, and when combined with an El Niño event, creates more with rain and wind than anywhere else on the planet. Current changes to global climate have only made this more acute. “Storms have always happened, but you’re getting a lot more of them and they’re a lot more frequent now,” says James Russell, an associate professor at the University of Auckland who studies endemic species on South Pacific islands (and how to save them).

Sandy, low-lying islands aren’t particularly fixed, like a continent. They’re incredibly dynamic, and move around a lot. Barrier islands are basically perpetually rolling over, and sometimes disappear and reappear, or split in two, or migrate up a coast. This happens with atolls, too—waves and storms and wind move sand and sediment around. Sometimes that’ll mean what was once a sandbar will breach the surface of the water, or an existing island will grow a new spit or just expand. And sometimes that means islands simply disappear. And all of this doesn’t even account for tectonic shifts, which can bring islands up and drop them down based on the level of the sea floor, or, for that matter, islands that spend part of their lives above water and part of them below, based on the tides. These aren’t really islands in the sense we’re talking about, since they can’t really support resident terrestrial life, but they will be relevant, for reasons we’ll see in a moment.

One big culprit that comes up when we talk about disappearing islands is sea level rise, of course. The seas as a whole, how this nearly global mass of interconnected water behaves, is insanely, insanely complicated and probably not very well understood by most people—many scientists included. Sea level was, for a few thousand years up to around the late 19th century, pretty constant, on average. Since the late 1800s, it’s been steadily rising. On average.

We keep saying “on average” because sea level changes are not the same in all places. In fact, in a lot of places, the sea level is dropping, and there are dozens of reasons for this inconstancy: some local, some regional, some global. Some operate on a decades-long cycle, or seasonally, or on a rhythm measured on a scale of millennia. Some are purely natural in cause, others can be pegged with near certainty to the influence of humans.

The period we’re in now is especially interesting and important with regard to disappearing land. The islands, they’re just a preview. The single largest cause of global sea level rise, right now, isn’t melting glaciers, but the phenomenon called thermal expansion. And it’s not particularly close. But that’s not going to be the case very much longer.

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter, including sea water, to change its volume in response to a change in temperature. When temperatures rise, water molecules absorb that extra energy and bounce around more. This takes up more space—not a lot of space, but some, and when you’re talking about something as massive as the global ocean, any small amount of expansion translates to a massive volume of water. Global temperatures have risen by about 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880, with most of that in the last half-century. And that means the water already in the ocean is getting bigger.

Researchers expect that this is just sort of the opening act for sea level rise. Widespread melting of glaciers and ice caps is next, which will have way crazier impacts on the ocean than just adding water to it. More water is the obvious one, but glaciers, as objects of great mass, actually have gravity, too—they pull water toward them. As they melt, they will lose mass, and in turn lose some of that pull. So coasts elsewhere will have to deal with expanding water, glacial meltwater, and normal sea water that isn’t as attracted to glaciers as it was before.

Yes, all of this is going to have a major impact on any low-lying land the world over. But the researchers I talked to for this story don’t necessarily think that islands are disappearing right now at a higher rate than they were in past centuries. Of the independent island nations most at risk of disappearing, Tuvalu is near the top of the list. But a 2018 Paul Kench study of all 101 islands—all small and low-lying—that make up Tuvalu reported that there’s no consistency in what is happening there at all. About three quarters of the islands actually grew in size, to one quarter that shrank, over the past 40 years. Overall, during this time period, Tuvalu grew almost three percent. This is not to say that Tuvalu isn’t in a period of intense crisis right now, because the country certainly is. But disappearing—which is a very specific thing—might not be the cause of that crisis, at least not today.

In general, the South Pacific is enduring sea level rise of about a fifth of an inch per year, according to a study from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology. So is there simply too much going on to be able to tell a clear story about the fate of these places? Ultimately, understanding what is happening now is about separating signal from noise, and realizing that the impacts of the direction that global climate is headed in are simply not going to be the same everywhere. It’s about understanding that a single, highly visible phenomenon is an inadequate proxy for changing climate. That doesn’t make the outlook—especially in the South Pacific—any less dire. What makes the South Pacific so worthy of study for basically any scientist concerned with the ocean is that, because these islands are so small and barely above sea level, small changes will make an oversize impact there. And an island doesn’t need to be actually underwater to become uninhabitable.

Remember the South Pacific Convergence Zone? All the typhoons and lashing storms? What’s clearly happening now are bigger, more frequent, and more destructive waves and storms. Couple that with what is to come, and the uncertainty starts to vanish. “Anthropogenic sea level rise is starting to kick in, but it’s not a big deal,” says Ashton. This means thermal expansion is already happening, but its impact isn’t severe. But when glacial melt really starts? “By mid-century, and especially end of century, [that] will be the dominant signal.” That’s a scientific way of seeing that we ain’t seen nothing yet.

Paul Kench’s work—which ran counter to the narrative that the days of the low-lying, habitable islands that we know are gone—angered some, who see it as unhelpful to the very real plight of Tuvalu and other South Pacific island nations. But Kench notes that the mere disappearance of some islands shouldn’t be the whole story. Those harsher and more frequent storms send waves of salt water inland—sometimes over entire islands, sometimes into fields, or into fragile island freshwater sources. Homes and infrastructure are at risk, as are the unusual plant, insect, and bird species found on small islands and nowhere else. Scientists are already exploring simply moving endemic species to more stable islands.

Whether these islands are, in the short term, growing or shrinking is immaterial to their residents if they can no longer trust the ground beneath their feet. The more the islands themselves move, the more they become volatile, unreliable, resource-poor—potentially uninhabitable. “Some island nations, there’s no high land, really,” says Ashton. “Their only prospects are to live on these shallow islands that are going to start moving around more and more rapidly as sea level rises.”

What’s happening in the South Pacific isn’t normal, and it isn’t good. Islands disappearing just isn’t the most useful metric to understand where the region is going. Focusing on that does the people of Tuvalu, of Micronesia or Kiribati, or the Maldives in the Indian Ocean, a disservice. The bigger problem is what is actually disappearing, and that is any sense of stability, security, even hope that the cultures on these islands aren’t simply playing out the clock on the ability to exist as they have for hundreds of years. It’s something that people who live on continents, buffered from the whims of the sea, don’t understand just yet. It probably won’t be long before we do, though.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook