Why Brigham Young University Had a Secret Cola Vending Machine

The complex relationship between Mormons and caffeinated soda.

There’s a joke in the Mormon community that requires a bit of translation for outsiders. Here goes: “How do you tell the difference between a good Mormon and a bad Mormon?” The answer? “By the temperature of their caffeine.” It’s often claimed that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints prohibits their members from consuming caffeine. In 2012, many news outlets were consequently whipped into a frenzy by sights of Mitt Romney clutching an occasional Diet Coke during his presidential campaign.

The truth about Mormons and caffeine, however, is far more complicated, and even members of the church disagree about this relative ambiguity in their scripture. The debate stretches back two centuries, divides husbands and wives, and, in the 1970s, resulted in a secret, “black market” vending machine of caffeinated sodas, hidden in the labyrinthine theater department of Brigham Young University.

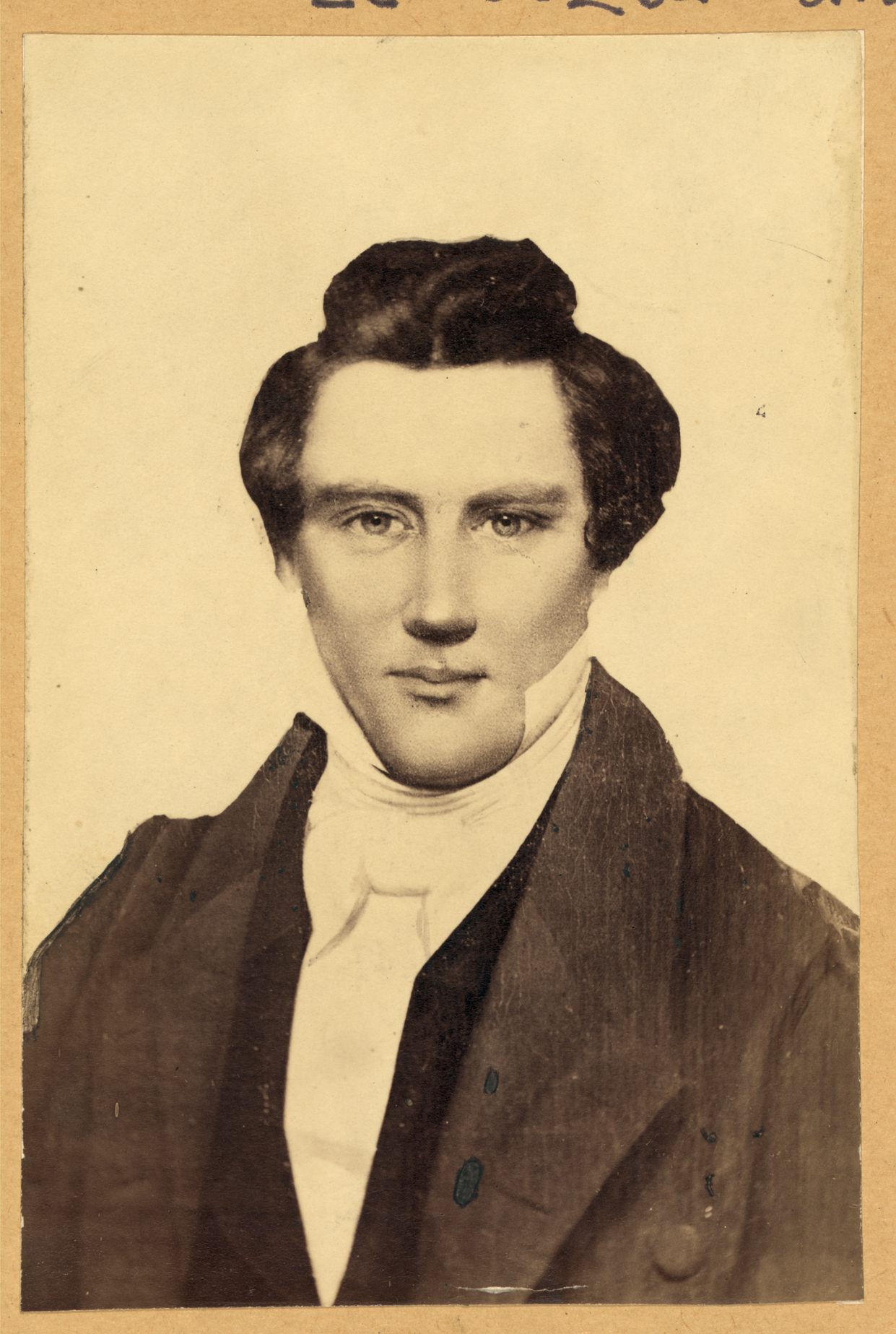

The confusion dates back to 1833, over 50 years before Coca-Cola and caffeinated sodas even existed. On February 27 of that year, Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism, received a Revelation from God, known now in Mormon circles as the Word of Wisdom. This tract lays out what Mormons can and cannot consume. It’s mostly straightforward, and not that different from modern advice on staying healthy: Wine and “strong drinks” are out, tobacco is “not for the body,” fruit and vegetables should be eaten in abundance, and meat is a treat for special occasions.

The church was cautiously enthusiastic about this frugal decree, voting in 1836 to replace wine with water in services. The following year, members agreed that anyone who did not follow the Word of Wisdom “according to its literal meaning” would be penalized and would not be “fellowshipped.” All the same, it took time for the Word to be followed absolutely. Smith himself continued to drink beer and wine at least as late as 1836. (He wrote in his published diary that “our hearts were made glad with the fruit of the vine.”)

But there was one contentious line in the Word that continues to inspire debate. “Hot drinks,” Smith wrote, “are not for the body or belly.” This appears to refer to tea and coffee, both popular beverages in 1830s America. Some modern Mormon scholars have argued that this is because these drinks are often served at near-boiling temperatures, causing a detrimental effect to both the body and the teeth. But others wonder if “hot” refers instead to the caffeine in tea or coffee, citing an 1828 Webster’s definition of “hot” that gives “stimulating” as one of its meanings.

The subsequent leaders of the church were similarly divided on Smith’s exact meaning. Which was the problem—the steam, or the stimulant? While they didn’t forbid it outright, early church leaders urged against Coca-Cola. In 1921, the Church President Heber J. Grant called it a “drug that creates an appetite for itself,” though it’s hard to know how much of that has to do with the (admittedly minimal) cocaine that Coke contained at the time. (Smith himself died in 1844, many years before Coke was even invented—and so was unable to clear up the ambiguity.) In the 1960s, the focus of the ban appeared to be on caffeine, rather than the temperature at which it was drunk: A conference report from 1965 includes “a little caffeine” on its list of “springboards to disease, broken homes, immorality, disloyalty to God, physical death, and the death of many of our eternal interests.”

Then-President David McKay took a generally looser view. That year, he wrote to a concerned Mormon that decaffeinated coffee was not “a violation of the Word of Wisdom”—but a 2005 biography describes him enjoying rum cake. (“The drinking of alcohol was forbidden,” he apparently said, “not the eating of it.”) On another occasion, he told a host that he would drink from any cup, “as long as there is a Coke in the cup.” Nonetheless, in the 1970s, the church bulletin spelled out its position on these “cola drinks” in full: “The leaders of the Church have advised, and we do now specifically advise, against the use of any drink containing harmful habit-forming drugs under circumstances that would result in acquiring the habit. Any beverage that contains ingredients harmful to the body should be avoided.”

In the years since, Mormons have come and gone on how the issue plays out in their day-to-day lives—leading, in the 1970s, to a “secret” cola-drink vending machine in the depths of Brigham Young, the Mormon university. Cartoonist Greg Kearney attended the Church-owned university as an undergraduate from 1976 to 1980. He put himself through college by working as a draftsman for the theater department in the university’s Franklin S. Harris Fine Arts Center. This, Kearney says, was a vast warren of rooms and storerooms, filled with theatrical props ranging from tables to typewriters. One such prop was an old-fashioned vending machines—the kind that took quarters and held glass bottles.

“It was fully functional,” Kearney says. “You could plug it in and the refrigeration would come on.” At the time, caffeinated sodas were forbidden on campus, but Kearney remembers a number of professors in the department with a taste for forbidden pops. The vending machine, he says, was duly plugged in and “buried” somewhere in the Center, serving as “their secret stash of caffeine-laced, illicit soda drinks.” Student workers like himself, he says, “would take the departmental truck down to the local Pepsi-Cola bottling outfit, and they would buy bottles of it, and stick it in the machine.”

At the time, all vending machines on BYU’s campus were controlled by Vending Services, who forbade caffeinated soda. “They would keep getting wind of this thing, and they could never find it,” Kearney says, chuckling. “Every time somebody from Vending Services would show up, Lee Walker would say, ‘I don’t know anything about that,’ and the next thing you’d know, we’d have to go and move it to some other place in the building.” It was a kind of open secret, he says. “Anybody from my time period would recall the ‘black market’ soda-pop machine that the theater department kept going.” (Karl Pope, a retired professor who taught in the department, remembers the machine, though he says it was not a secret—and that its fizzy spoils included Dr Pepper and caffeinated root beer.)

In the years since, Mormons have tussled on online forums, around lunch tables, and even in marriages. Isaac McCluskey’s family are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in New Zealand. Growing up, his father was stringently anti-Coca Cola, but would occasionally partake of a hot chocolate or herbal tea. “His reasoning was caffeine’s addictive qualities,” McCluskey says. His mother, on the other hand, was a “closet diet Coke drinker.” “I can still remember being 14 or something, and seeing a Diet Coke bottle in the car,” he says. He confronted his mother about it, who sat him down and explained that “all was not as it seems when it came to the consumption of Coca-Cola.” (The bottles were left in the car: McCluskey’s father would immediately dump any soft drink with caffeine in it that he found in their home.)

For a long time, members of the church have been keen to tease out this thorny problem. “It’s highly up for interpretation within the church’s normally rigid structure,” McCluskey says, “which creates a framework for people to almost … rebel.” These rebellions are comparatively small, but have a certain symbolic importance. In the years since, however, McCluskey’s father has relaxed a little, he says. Part of this may be due to a clearer position from the church. In late August 2012, NBC News ran an hour-long feature on Mormonism, in which they said that caffeine was verboten. Not so, said the LDS church on its website, publishing a statement which explained that “the church does not prohibit the use of caffeine” and that the faith’s health-code reference to “hot drinks” did not go beyond tea and coffee. The following day, they updated it once again. “The church revelation spelling out health practices … does not mention the use of caffeine.”

The change allowed Mormon Dr Pepper and Coca-Cola drinkers to finally enjoy their poison in public, but it was not until September of last year that Brigham Young University finally caved. In a public Q and A, the university’s Dining Services explained that “Consumer preferences have clearly changed and requests have become much more frequent.” Coke—with caffeine!—would be served, with no need for the secret vending machines or unauthorized delivery services of yore. But those seeking a still harder option are still obliged to go elsewhere: Mountain Dew and Red Bull remain firmly off the menu.

*Correction: This post previously called the vending machine a “Coca-Cola vending machine.” It served a variety of soft drinks.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook