Chemirocha: How An American Country Singer Became A Kenyan Star

Hugh Tracey in the International Library of African Music at Msaho, Roodepoort 1960s. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

There’s a song drifting around the backwaters of the internet called “Chemirocha.”

It’s a scratchy field recording made in Kenya, in 1950, of a little village girl singing with her friends. Someone in the background strums a sort of makeshift lyre called a chepkong. The entire recording is only 90 seconds long, but it has an arresting, unearthly beauty. It’s the sort of thing that once lived only on freeform radio stations at the left of the dial, or on worn-out mix tapes passed between obsessive collectors. Now it’s on YouTube and Soundcloud.

Anyone can hear the song’s appeal. But there’s something that turns simple fans of chemirocha into fanatics—enthusiasts and evangelists who bring up the song at dinner parties or cocktail hours; who use it to enliven a weary work happy hour or impress a date with their acumen. And that is its backstory.

According to Hugh Tracey, the ethnomusicologist who made the recording in 1950, British missionaries had come through the village some years earlier with a wind-up gramophone, and played American country records for the Kipsigis tribe. They loved one singer in particular. They couldn’t believe their ears, that a human being could sing and play like this. So they decided he must be a sort of deity, half-man and half-antelope. The Kipsigis created a whole legend around this country singer, who was Jimmie Rodgers, the “father of country music.” They pronounced his name “Chemirocha.”

Hugh Tracey tells this story himself before introducing the song on the 1952 LP he released of his Kenyan recordings, Music of Africa Volume 2:

It’s a great story. Except that it’s probably wrong and possibly racist, or at least incredibly reductive. “Simple villagers encounter Western culture and elevate white people to the status of gods” is a catchy and convenient tale that we’ve heard too many times.

To explain Hugh Tracey’s account, we don’t have to look much further than the milieu he came from. Tracey was a British émigré who arrived in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1921, to help his brother farm tobacco there. He learned the local dialect while working in the fields, and quickly grew to love the traditional music, ultimately becoming the Alan Lomax of sub-Saharan Africa.

Inside ILAM, The akadinda (large xylophone), kalimbas on the wall, and a photo of Hugh Tracey. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

He spent six decades traveling the continent and made over 40,000 recordings of the music he found there, from Pygmy yodels to Zulu choral music. He was almost always the first person to document this music. Along the way, he created a library to house all of this material: the International Library of African Music (ILAM), at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, South Africa.

Hugh Tracey died in 1977. His son Andrew Tracey then ran ILAM for the next 28 years, retiring in 2005. The current director of ILAM, and the keeper of Hugh Tracey’s extensive collection of notes, recordings, and African musical instruments, is a woman named Diane Thram.

Philip Cheruiyot (center left) leans in to read the song titles on the CD booklet brought by Diane Thram. Cheruiyot’s grandfather sang on Hugh Tracey’s recording of “Chemirocha II.” (Photo: Ryan Kailath)

When she took over in 2006, Thram set about cataloging and digitizing the massive ILAM collection. That’s when it occurred to her that most of the musicians in Hugh Tracey’s collection had never heard their own recordings. “I remember having this realization one day,” she says, “that now that we know what we have, it’s time to give it back.”

Thram teamed up with Tabu Osusa, whose record label, Ketebul Music, archives rural Kenyan music and hunts down obscure and forgotten Kenyan folk recordings from the past. Together, Osusa and Thram set out to bring the recorded music back to the people who created it.

“It’s not fair for them,” says Osusa, “that their music was recorded, and they have no idea that music exists! So, I think this is the right thing to do. Take the music back to the people, so from then on they know—this was ours.”

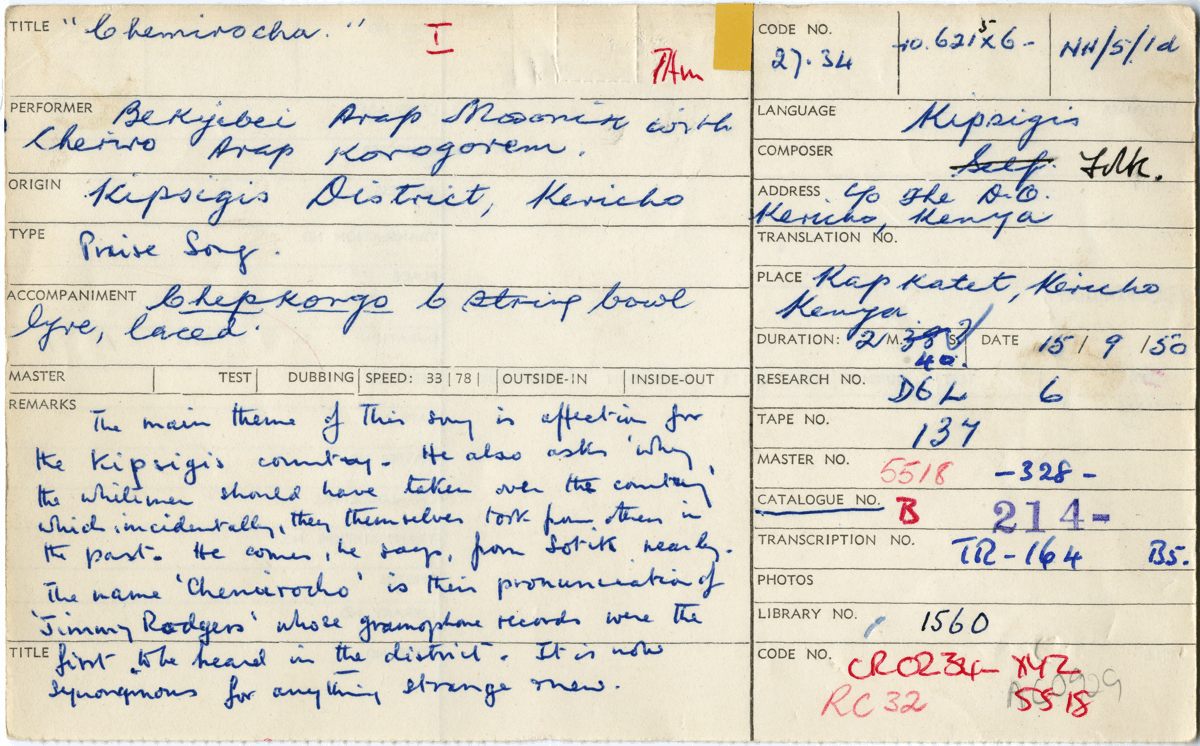

Hugh Tracey’s original field notes for “Chemirocha I.” (Photo: Courtesy International Library of African Music)

Luckily for the pair trying to retrace his footsteps, Tracey took extensive field notes, including the names and locations of the performers he recorded. It was in these notes that Thram made a surprising discovery. “Chemirocha” was actually “Chemirocha III”: the last of three separate chemirocha songs that Tracey recorded that day in 1950.

“Chemirocha I” and “II” were sung by men. “The main theme of this song,” wrote Tracey on his field card for the first song, “is affection for the Kipsigis country. He also asks why the white man should have taken over the country…the name ‘Chemirocha’ is their pronunciation of ‘Jimmy Rodgers,’ whose gramophone records were the first to be heard in the district. It is now synonymous for anything strange + new.”

Jimmie Rodgers, American country singer. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Already Tracey’s notes belied the popular “primitive” reading of the Kipsigis and their reaction to chemirocha. But for the whole truth, Osusa and Thram would have to find a handful of Kipsigis villagers in an area roughly the size of Ireland: Kenya’s Great Rift Valley.

To start the search, two locals were sent on a reconnaissance mission, including one Ketebul employee, Sapat Opipohott, and a Kipsigis fixer known as 50 Cows (cows are an important status symbol in Kipsigis culture; his name is a play on that of the rapper 50 Cent).

“If you don’t have somebody on the ground that the people know, they don’t trust what you’re doing,” says Opipohott. “If you’re looking for certain families, everybody will be curious: ‘Why are they looking for that family? What have they done?’”

Elizabeth Betts (holding CD) was a little girl the day that Hugh Tracey recorded thirty songs in her village, in 1950. This picture was taken shortly after Betts heard those recordings for the first time. To her right is Diane Thram, director of the International Library of African Music. (Photo: Ryan Kailath)

After encountering suspicion and mistrust all over the Rift Valley, they found enough of a lead to bring Thram and her team out to the bush. One of the first people they met was Elizabeth Betts. Now an old woman, she was a little girl on the day that Hugh Tracey recorded 34 songs in her village of Kapkatet. She could still sing all of the songs by heart.

“Where did those songs go to?” asked Betts via 50 Cows, who translated. “I would be happy if we could go back to singing like those days.”

Everywhere the team went, they encountered people who knew and remembered the songs Hugh Tracey recorded, though none remembered the recording session itself. And interpretations of what the word “chemirocha” actually meant varied wildly.

Many families had no way of playing the CDs they were given. Here, a borrowed laptop is rigged up to a portable radio—connected to a speaker powered by a car battery—in order to play the CD. (Photo: Ryan Kailath)

Patricia Lasoi, Minister of the Kenyan district of Bomet, agreed that “chemirocha” was just a word for Jimmie Rodgers. But her adviser said that it had come to stand for a whole genre of “slow, nice music” and “classic songs.”

Philip Cheruiyot, grandson of one of the male singers of “Chemirocha II,” said that because his grandfather was a musician, he took the term as a nickname, and was known as “a chemirocha of the village.”

And Steve Kivutia, a member of the ILAM expedition, recalled that when he was young, if you were a tough guy around town, you were known as a “Jimmie”—after the rough and ready cowboy Jimmie Rodgers.

Philip Cheruiyot (center, in sportscoat) is surrounded by friends and family as Diane Thram explains what is on the CD she has brought him. Cheruiyot’s grandfather sang on one of the songs on the CD, recorded in 1950 and never before heard in the village. (Photo: Ryan Kailath)

Then, after days in the field, Thram and her team found their key witness. Josiah Arapsang is son of the Kipsigis District Chief who organized all the local singers and musicians for Hugh Tracey to record that day. Arapsang was eight years old then, and recalled the scene. But when presented with Tracey’s “half-man, half-beast” formulation, he laughed.

He said that yes, the Kipsigis thought that “chemirocha” was half-beast, because they thought that all white people were half-beast—and not in the sense of deities. For one, the white missionaries who came through their village ate an unfamiliar food that looked like worms (white rice). Further, the missionaries preached about literally eating the body and blood of Christ. And then the Kipsigis men were rounded up, without warning, to give blood for the war effort.

A road in the Rift Valley, Kenya, c. 1936. (Photo: Library of Congress)

“What the colonial government used to do,” Arapsang explains, “they will just collect you, put you into a vehicle, rush you to the hospital. The Kipsigis had never seen people hooked up to bags to give blood before.

So, as Arapsang says, they thought, “‘Aha! These people—they are man-eaters.’ As a result, they formed the idea that ‘yeah, this one is a human being, but half-animal, because he eats people.’”

Half-man, half-beast “chemirochas.” Far from the popular conception of the myth is the deliciously ironic truth: the Kipsigis villagers are the ones who actually thought the white Europeans were savages.

Cheruiyot Arap Kuri, born in 1926, sang on Hugh Tracey’s 1950 recording of “Chemirocha I.” This picture was taken moments after he heard that recording for the first time. (Photo: Ryan Kailath)

After a week in the field, Thram found Cheruiyot Arap Kuri. Now 88 years old, he was one one of the actual musicians performing on “Chemirocha I.” Upon meeting him, Thram was visibly overcome by emotion: “It’s like a dream come true to find someone who’s still alive, who played this music on that day.”

She presented him with a CD of Tracey’s recordings, and with 50 Cows translating, explained their origin. Like Elizabeth Betts before, Arap Kuri recalled the songs as soon as he heard them again, and even began to sing along with some. Thram asked if he remembered the white man who came and made the recording.

“We never understood what the white man was doing,” says Arap Kuri via translation. “We were just singing for him and having fun. All those other old men who sang together have passed on, and I sang with all of them.”

Arap Kuri continued, “I am very happy you have come back with this,” he told Thram. “I always wanted to imagine where are those songs, and the singers in those days who all went their own way.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook