Decoding Bhutan’s Love Affair With Chili Peppers

In the small mountain country, spicy peppers dominate breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

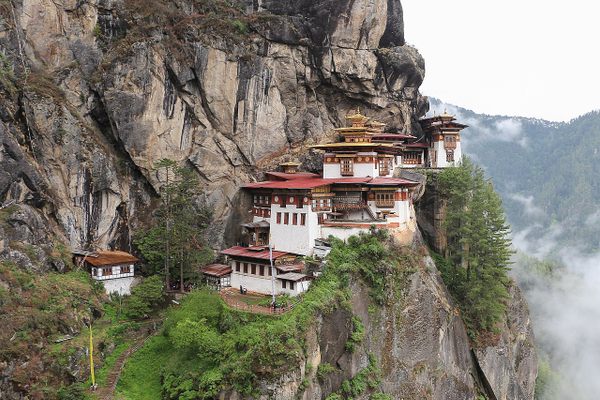

Tucked away in the folds of the Himalayas, Bhutan generally manages to stay under the radar. In the larger world, knowledge about this small Buddhist country is limited.* Bhutan may be best known for its unique Gross National Happiness metric, which is used to measure the welfare of its citizens in lieu of traditional economic measures.

For foreigners who visit, the country’s mountain landscapes prove memorable. But another unique aspect of Bhutan stands out: the Bhutanese’s extravagant love of chili peppers.

Bhutan’s summer markets are a feast for the senses. Young women in colorful kira dresses sell Buddhist masks, Tibetan prayer bowls, and good luck charms. Older women hawk bundles of hard chhurpi cheese, while housewives sift through dozens of varieties of red rice. And at every stall, there are huge piles of green and red chili peppers, with the occasional yellow pepper peeping through.

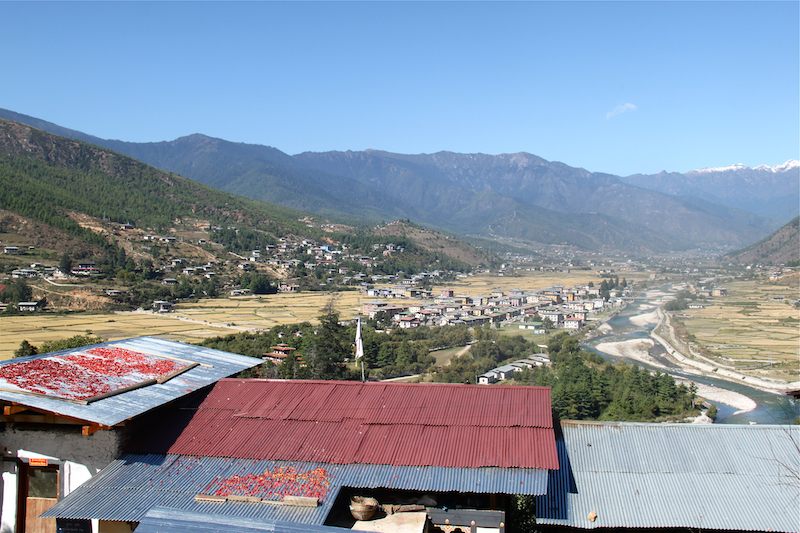

This abundance of chili peppers isn’t just found at markets. Shops in Bhutan feature heaps of spicy peppers, and along Bhutan’s hilly roads, you’ll see red chilies laid out to dry on rooftops like scarlet carpets or hung out on balconies like misshapen curtains. And in the valleys of rural Bhutan, during festivals and prayer rituals, the pungent odor of burning chilies floats in the air, along with the sounds of prayer bells and hypnotic chants.

The result is a food culture defined by chili peppers, which are used more like a vegetable than a spice or condiment. Given Bhutan’s proximity to India and China, influences from both countries’ cuisines (especially Tibetan) are strong. Yet Bhutan’s national dish is unique: ema datshi, a stew of equal parts chili peppers and soft cheese, along with onions and tomatoes. Ema datshi is present at every main meal of the day, with the chili peppers—usually green and sliced lengthwise—carrying a spice hit that even the cheese cannot soften.

Ema datshi is the star of Bhutanese cuisine, and while many variations feature potatoes (kewa datshi), beans (semchung datshi), or mushroom (shamu datshi), there is always a generous sprinkling of chilies. Chef Sonam Tshering, culinary instructor at the Royal Institute for Tourism and Hospitality, says that all Bhutanese curries contain chilies in copious quantities. Another dish easily found in Bhutanese homes is ezay, a coarse chili dip eaten at breakfast.

Culinary experts say that the most likely reason for chili peppers’ predominance in the Bhutanese diet is the sensation of heat they provide during cold winters. Because when people say that spicy food is painful, they’re being accurate. Chili peppers trick our pain fibers to react the same way they do to extreme temperatures, leading to a warm feeling that is often uncomfortable.

For this reason, humans are the only mammals to eat—and actually enjoy—the pleasure-pain of chili peppers. As one science reporter put it, it takes “a complicated brain and weird self-awareness to enjoy something that is inherently not enjoyable,” and researchers have suggested that a love for spicy foods is similar to thrill-seeking behavior that pushes people onto roller coasters and into high-stakes gambling.

Spicy food causes pain. But for anyone with Bhutanese levels of spice tolerance, after the initial shock of watery eyes and burning subsides, a feeling of warmth and well-being remains.

This may seem odd, since nearby tropical countries like India use peppers so much in their cuisine. But the effects of food on temperature are contradictory. Ice cream provides a pleasant coldness on summer days, but digesting all that fat, according to food scientist Barry Swanson, actually warms you up. Spicy food makes the Bhutanese feel warm, but since it causes sweating, it also cools people down in India’s heat.

It’s telling that even in Bhutan, no one takes naturally to eating copious chili peppers. Jose Thachil, Executive Chef at the Taj Tashi hotel in Thimphu, says that eating chili peppers starts from a very young age. Bhutanese parents essentially train children to tolerate spice by giving them small (and then increasingly large) portions with their food.

There is an interesting parallel to this in the folklore of neighboring India: the vishkanya (literally translated as “poison girl”). Ancient texts about statecraft mention young girls who are trained to be assassins. From a very small age, they are brought up on a steady and careful diet of snake venom and antidote that makes them immune, but their victims vulnerable.

Cuisine apart, chilies also find a place in larger Bhutanese culture, primarily during prayer rituals. Many Bhutanese consider chilies to have supernatural powers, and burn them to keep away evil spirits. “My grandparents burned chilies whenever someone fell sick at home,” reminisces chef Tshering, “because they say that when we burn chilies, the evil spirits will suffer and stay away from the family.”

Chef Thachil also recounts a belief about Ara, the popular home-brewed rice or maize liquor of Bhutan: Locals tend to drop several chilies into their bottle of Ara, not to impart any special flavor, but for good luck and to ward off evil alcohol spirits.

Despite all this love, chili peppers are not native to Bhutan, or even the Asian continent. They were originally cultivated in South America, and brought to India by Portuguese explorers in the early 16th century—along with the potato and tomato.

But now chilies are so deeply entrenched in Bhutanese cuisine and culture that they’re beloved for far more than their original, warming appeal. “It has just been our tradition from a long time,” says Chef Tshering. “We now eat chilies even during our summers.”

In my own encounter with ema datshi, I remember my heart leaping at the promise of spiciness and flavor. One of the things I sorely miss when I travel out of India is heat in my food. But ema datshi was too hot—even for my palate shaped by years of fiery mango pickles and pungent stews.

Seeking out super spicy foods and entering hot pepper eating contests has become part of modern food culture. But the Bhutanese eat ema datshi as if it were peanut butter. Indeed, my guide laughed gently as he reminded me that his ten-year-old regularly tucked into it without a problem.

*Correction: A previous version of this post included a note on Bhutan’s system of government.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook