The Depression-Era Glassware That Came in Boxes of Oatmeal

These vibrant dishes helped cheer up Americans during a bleak time.

Imagine wandering into the kitchen for breakfast, opening a package of Quaker Oats, and finding a glass teacup inside. That’s what happened during the 1920s and 1930s, when ubiquitous household goods, such as bags of flour and canisters of tea, included unusual trinkets.

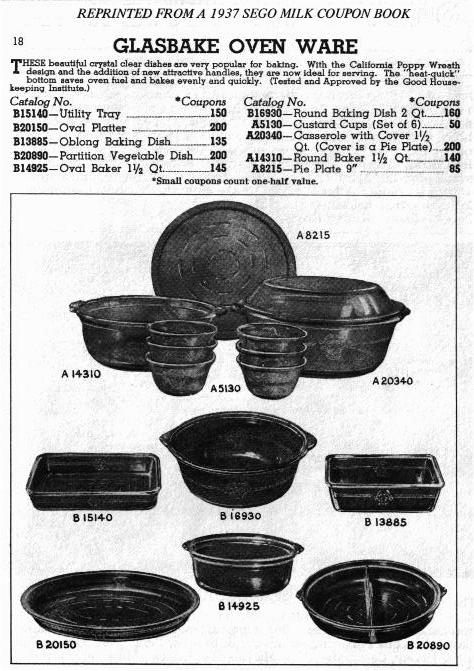

During the Depression era, companies in the United States would tuck away beautifully-patterned dinnerware—including teacups, saucers, and bowls—into their products’ packages. Depression glass, as it was known, was so cheap to produce that heavy-hitting companies of the time, such as Phillips’ Toothpaste and Wheaties, gave them away in their products. It wasn’t just relegated to home goods, either. Back then, moviegoers could take home glassware on “dish nights.” Folks received dinnerware pieces while getting their tanks topped off at the gas station, too.

More than a marketing gimmick, Depression glass brought much-needed joy into kitchens during a particularly bleak time in American history. In just the first year after the stock market crash of 1929, the number of unemployed adults in the U.S. doubled, from roughly 1.6 million to 3.2 million. By 1933, that number had climbed to 13 million. The staggering economic downturn took an emotional and psychological toll as well, with suicide rates and alcoholism levels rising astronomically. Millions of people had little hope for the future.

Prior to the crash, most glass dinnerware was often clear, and handmade from cut crystal. It cost too much, for even a typical middle class family budget. After Black Tuesday, such extravagances were all but forgotten, as scores of Americans stood in lines waiting for bread.

But a revolutionary machine that used new processes such as mold etching—a method that utilized acid to etch patterns into an iron mold rather than directly onto the glass—made manufacturing glassware quicker and cheaper. The molds themselves were costly, but each one could produce thousands of dishes. Thanks to mechanization, one Depression glass manufacturer, Anchor Hocking, increased glass production from one piece per minute to over 90 pieces per minute. This allowed companies to sell individual dishes, such as tumblers, for a nickel or less.

“Depression glass was the first glassware in American history to be produced by a completely automated method without need for skilled glass blowers, so the major glass companies could sell complete 20‐piece dinner sets for as little as $1.99,” wrote Diane Greenberg in The New York Times, years later. It also meant that many American families could afford to purchase beautiful glass cups, plates, bowls, and pitchers in brilliant shades for the first time.

As the glassware adorned tables and cupboards, it lifted families’ spirits. “They glimpsed an old, sweet dream shining in the darkness just ahead of them,” wrote Hazel Weatherman in Colored Glassware of the Depression Era. “For many, many families [the Depression glass] became something they could focus on, group around, work towards, in its own small way.”

For less than the price of a box of cereal, this glassware represented a glimmer of optimism that could sit on a shelf. Even the most meager dishes, such as creamed chipped beef on toast, seemed more nourishing when served up on a pretty plate. Popular patterns included the Adam, from the Jeannette Glass Company, which came in translucent rose and green, with delicate feathered patterns etched onto the glass. The Cherry Blossom pattern dishes, etched with designs inspired by cherry trees, appeared in a pearly blue.

Today, Depression-era dinnerware has transformed into nostalgic kitsch for vintage lovers and glass collectors of the Instagram generation. Hungry thrifters scour antique booths and glass shows, hunting for their favorite colors and patterns. “I imagine my hardworking Southern grandmother anticipating the treasure that would arrive in the next box of oats,” writes Sharon L. Palmer, in Antiques & Collecting. “Perhaps it would be a perky little creamer to cheer her dim dining room at a time when putting food on the table was a small miracle… this was an era that saw half of the glass companies shut down for bankruptcy, merger, or fire, you name the catastrophe. Did my grandmother ever suppose that in another 75 years, I might be holding a little creamer identical to hers, wondering whether I should shell out $40 for it?”

Depression glass clubs exist coast-to-coast throughout the United States, providing members the opportunity to display their collections and talk about their shared passion. The Kansas-based National Depression Glass Association hosts yearly conventions featuring guest speakers. Local clubs, such as the Peach State Depression Glass Club in Marietta, Georgia, exist to “promote interest in and spread knowledge about glassware of the Depression era.” They meet on the second Tuesday of every month to share their latest finds and view other members’ collections. Each spring, they also hold a member’s collectibles auction.

The irony of collecting this dinnerware isn’t lost on people, either. “Take a look back and you will see cheap, glass-filled dime store shelves and Americans escaping the harshness of everyday life by going to the movies and stashing a much-needed cup and saucer away in a handbag as an extra bonus,” writes Palmer. “Today’s collectors stroll through giant shows held in lavish ballrooms and feverishly try to outbid each other on eBay for that elusive pitcher.”

These pitchers may be hot ticket items now, but during one of the country’s most trying decades, dinnerware was more than just bric-a-brac for a china cabinet. During the Depression, someone could pull a teacup out of an oatmeal box and hold it up to catch the sunlight streaming in through a kitchen window. In that moment, things didn’t seem quite so dark.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook