Found: The Wreck of a Ship That Carried Enslaved Maya from Mexico to Cuba

This slave trade is well known to historians, but this is the first known wreck from it.

On September 19, 1861, a steamboat caught fire and sank in the Gulf of Mexico, two nautical miles from the Yucatán port town of Sisal. There were dozens of confirmed casualties, passengers and crew alike. But the full death toll will likely never be known, because the enslaved Indigenous Maya people held on the ship were never counted in the first place—they were simply listed as cargo.

Archaeologists from Mexico’s Sub-Directorate of Underwater Archaeology (Subdirección de Arqueología Subacuática, or SAS) announced recently that they’d identified the underwater remains of this ship, La Unión. Between 1855 and 1861, the Havana-based vessel brought, on average, 25 to 30 enslaved Maya people from Mexico to Cuba every month. The enslaved persons were then sold upon arrival in Havana.

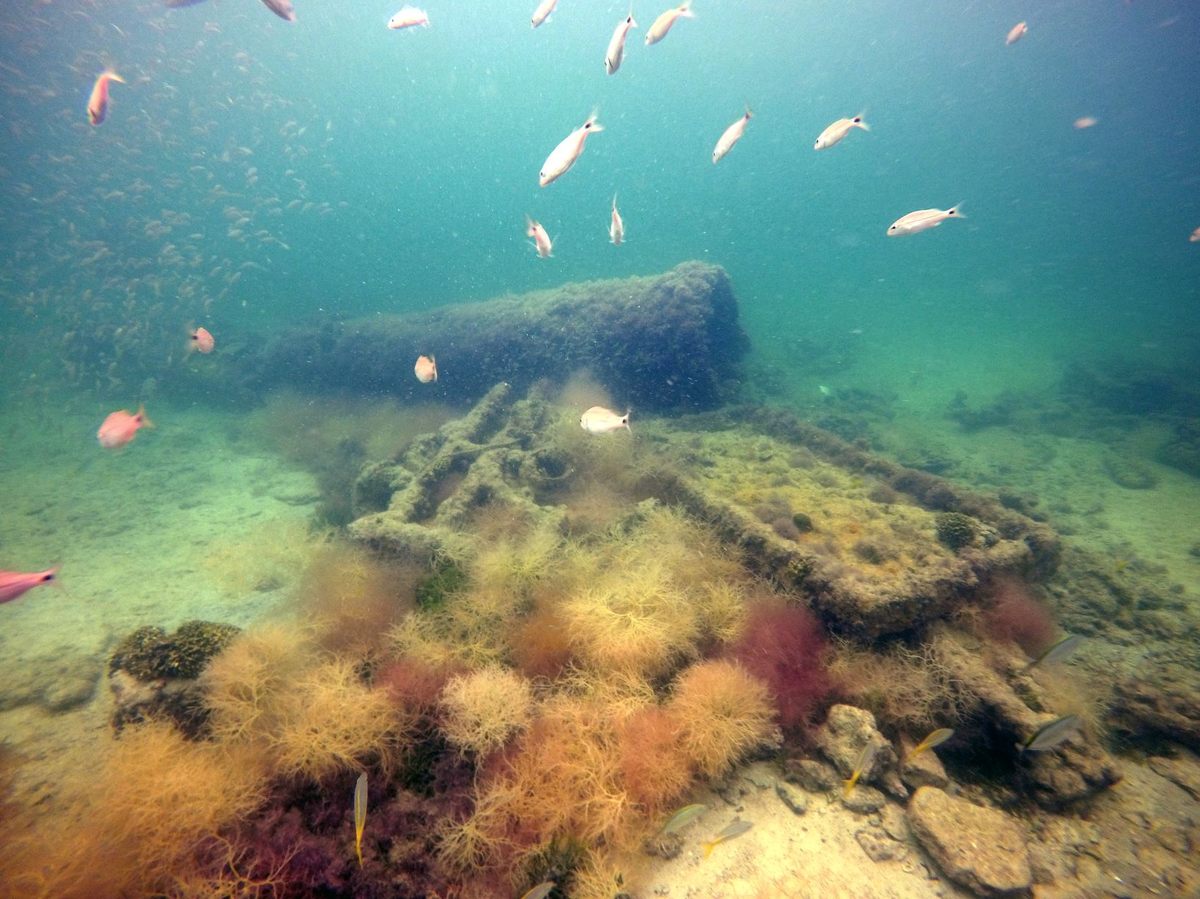

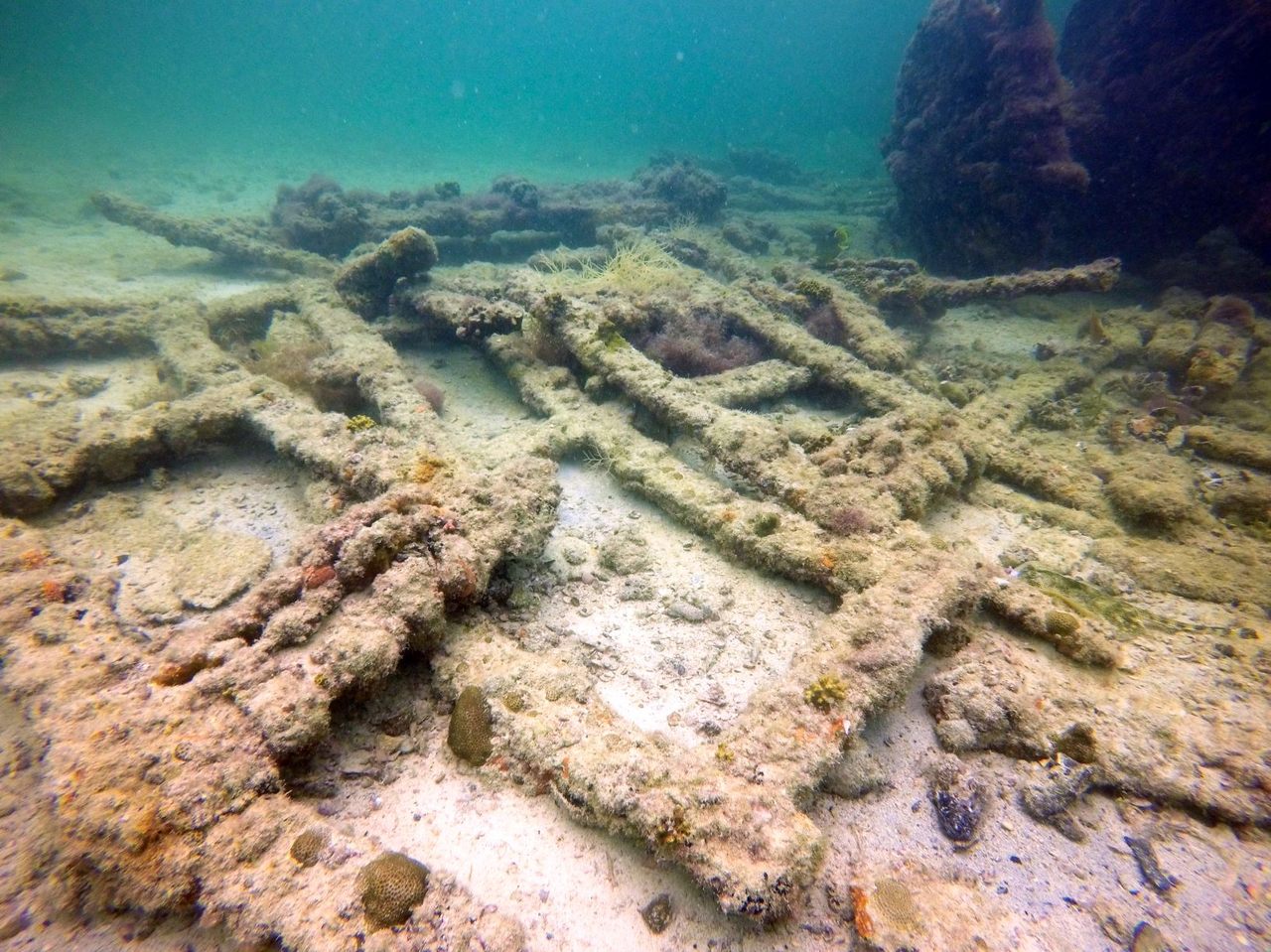

The shipwreck was first found in 2017, after researchers found an 1861 document in the Yucatán state archive describing the fire and the approximate spot where it occurred. Local fishermen, who had heard about the wreck in oral retellings, also helped guide the researchers toward the search area. In tribute to one of these fishermen, the researchers temporarily named the shipwreck “Adalio,” after his grandfather. While it was clear that the team had something significant on their hands, it took three years of interdisciplinary research to confirm that “Adalio” was, in fact, La Unión. It is now the first ship ever discovered known to have carried enslaved Maya people.

Helena Barba Meinecke, director of the Yucatán Peninsula division of the SAS, outlined her team’s research process in an email. One key clue that “Adalio” might really be La Unión was that its technological and skeletal components—the propulsion machine, boiler, axles, paddle wheels, and chimney—dated to the first era of steamboat technology (1837–1860), and La Unión began operating in 1855. In addition, the archaeologists found that the ship’s boilers had exploded and that its wood had been damaged by fire. Perhaps most importantly, the location of the wreck matched what was reported in contemporary accounts and documentation. Perhaps the eeriest find, however, was brass cutlery used by first-class passengers on La Unión, who would have been unaware of the enslaved people on board. The cutlery was also branded with the name of the shipping company that owned La Unión.

The enslavement of Mexico’s Indigenous population began during the so-called Caste War of Yucatán, a long-running conflict that lasted from 1847 to 1901. Promised, and then denied, tax relief in exchange for military service—as they saw private estates rise throughout formerly public lands—Maya communities on the Yucatán Peninsula rebelled against Mexico’s European-descended government, and sustained enormous casualties in the process. According to the University of North Carolina, the combination of death and desertion cut the peninsula’s population in half within just a few years, by 1850. In a brutal 1848 decree, Meinecke writes, the Yucatán governor ordered the expulsion of all Maya captured in combat. They would be deported to Cuba, still a Spanish colony at the time, to toil in the island’s sugarcane plantations. It was irrelevant to these officials that Mexico had officially abolished slavery in 1829.

Indeed, one illegal tactic put to use during the Caste War was the deployment of enganchadores. Sent with fraudulent documents into Maya communities ravaged by the violence, these kidnappers led people to believe that they would be settled on uninhabited Cuban land and live as farmers—though their true destination was a life of slavery. As late as October 30, 1860, La Unión was actually caught at sea carrying 29 enslaved Maya, including children as young as seven years old. Even this, however, failed to stop the trade. It wasn’t until the fire of September 1861, four months after President Benito Juárez issued a decree against further kidnappings, that the government crackdown became sufficient to prevent the deportations, even if the violence would continue in Mexico for decades to come.

Like other researchers of slavery, Meinecke points out a major gap in the otherwise rich historical record: In most cases, the identities of those who were enslaved remain unknown. At the same time, she writes, Maya descendants have been identified in various locales throughout Cuba, including Havana, Camagüey, and Pinar del Río, to name a few places. Meinecke is hopeful that continued engagement with these descendants, and the recording of their oral histories, might one day reveal just who their ancestors were.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook