How a King’s Feast of Sturgeon Sank to the Bottom of the Baltic Sea

In 1495, a fire destroyed a stately ship and sank a big fish.

More than five centuries ago, a fish in a barrel sank to a watery grave at the bottom of the Baltic Sea. The unfortunate aquatic creature was a sturgeon brought aboard Gribshunden, the 115-foot flagship of King Hans of Denmark, and it was as long as a person is tall.

Archaeologists retrieved the 524-year-old animal during underwater excavations in August 2019, along with a number of other remarkable items: coins featuring the face of King Hans, an alderwood tankard cut from a single piece of wood, remnants of mail armor, a crossbow stave, and even an arquebus hand cannon. But the sturgeon was truly unexpected.

“Around the Baltic in archaeological sites, particularly on land, there are little-bitty pieces of sturgeon that go back to prehistoric times,” says Brendan Foley, a marine archaeologist at Lund University in Sweden. “But nowhere has anyone found a complete, intact sturgeon in archaeological contexts.” Foley is the co-author of a recent study detailing the excavation of Gribshunden, published in the open-access Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. When the project started, he says, “a two-meter sturgeon wasn’t on our list.”

Gribshunden slipped beneath the waves after a deck fire in 1495. (King Hans was not on board.) In the 1970s, it was discovered by amateur divers off the coast of Ronneby, a town at the southern tip of modern-day Sweden, but the wreck only was identified as the famous flagship in 2013. Today, it sits on the Baltic seafloor under about 30 feet of water. The recent finds are some of the first steps toward better understanding the exquisitely preserved shipwreck.

Less than one percent has been excavated so far, Foley says, so the remainder could yield new wonders. “It’s just so fortunate that the Baltic is the perfect preserving environment for wood,” he says. “We basically found a ship in a pickle jar.”

The sturgeon, unlike the coins and weapons, doesn’t seem to have been an initial part of the ship’s manifest. When Gribshunden went down, along with its more precious cargo, it was on its way to an audience with Sten Sture the Elder. King Hans wanted Sten Sture to back his claim to the Swedish throne, and the vessel was loaded with goodies meant to dazzle him.

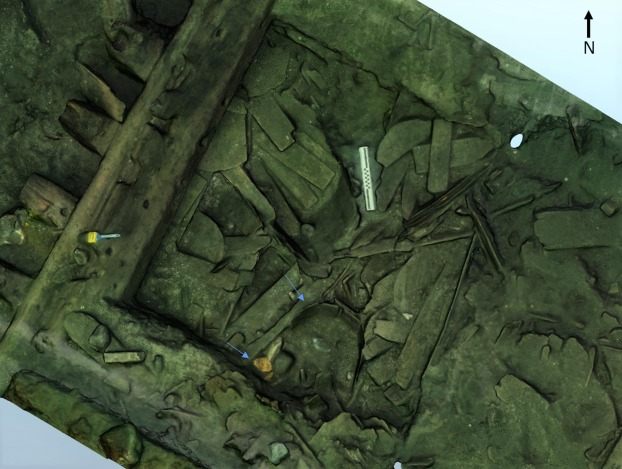

Foley’s team was given license to excavate directly downwards on an area a little smaller than the average parking space. As it turns out, they were digging straight into the hold—essentially the ship’s pantry. Unlike other barrels in the bunch, the sturgeon’s barrel was found upright, with the lid ajar, suggesting that someone had interacted with it while on board.

Though sturgeon have long been a royal fish in Europe, this fish was crudely hacked apart so that it would fit in the barrel that became its tomb. Its handlers didn’t bother to remove its scutes—the bony, armor-like plates that line the fish, and have protected the species for 200 million years—leaving ragged marks on the remains. The slipshod butchering suggests that it may have been a chance catch, Foley says.

“We think it’s significant that the body was roughly handled,” says Stella Macheridis, a prehistoric archaeologist and osteologist at Lund University, and the lead author of the recent paper. “That signals that maybe the catchers were not really familiar with how to process this fish, but they were able to recognize its significance.”

DNA analysis on the sturgeon led the authors to another striking realization: The Gribshunden fish was an Atlantic sturgeon, a species that has not been seen in Baltic ecosystem for a very long time. (Today, the only sturgeon that prowls the Baltic is the endangered European sturgeon.) So the sturgeon provided both historical and biological surprises, in one fell scute.

Foley, Macheridis, and the rest of the team plan to return to the site in November, barring any potential delays caused by the coronavirus pandemic. A shipwrecked sturgeon is an solid place to start, but there are plenty more finds to fish out of the water.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook