The Oldest Tapeworm Ever Was Just Found in Amber

Turns out the parasites used to plague dinosaurs, too.

At some point in the mid-Cretaceous period, a cartilaginous fish—an early ancestor of a ray or shark—was having a really bad day. For some unknown reason, it became beached on shore, unable to get back in the water. In addition to that, parasitic tapeworms were feeding in its intestines, meaning it had likely been experiencing discomfort even before it washed up on land.

Then came the fish’s fatal blow. A land predator—a dinosaur, mammal, or bird—ate the sea creature, ripping up its prey in the process. The fish’s severed intestine spewed the parasite onto a nearby tree. There on shore, the tapeworm got caught in the sap and eventually was fossilized in amber.

How do we know all this from 100 million years ago? Like detectives, scientists have puzzled the pieces together of the bizarre array of events from clues in the fossilized amber. They published their findings in the journal Geology, led by the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology.

“It was an accidental discovery,” says Cihang Luo, a PhD student at the Nanjing Institute, who specializes in Mesozoic invertebrates, namely insects trapped in amber. “I was studying roundworms found in the bodies of insects.”

Luo explains that finding roundworms in amber is “much more common” than finding a tapeworm. “When an insect is trapped in amber, the roundworms will try to escape the body of the insects,” he explains.

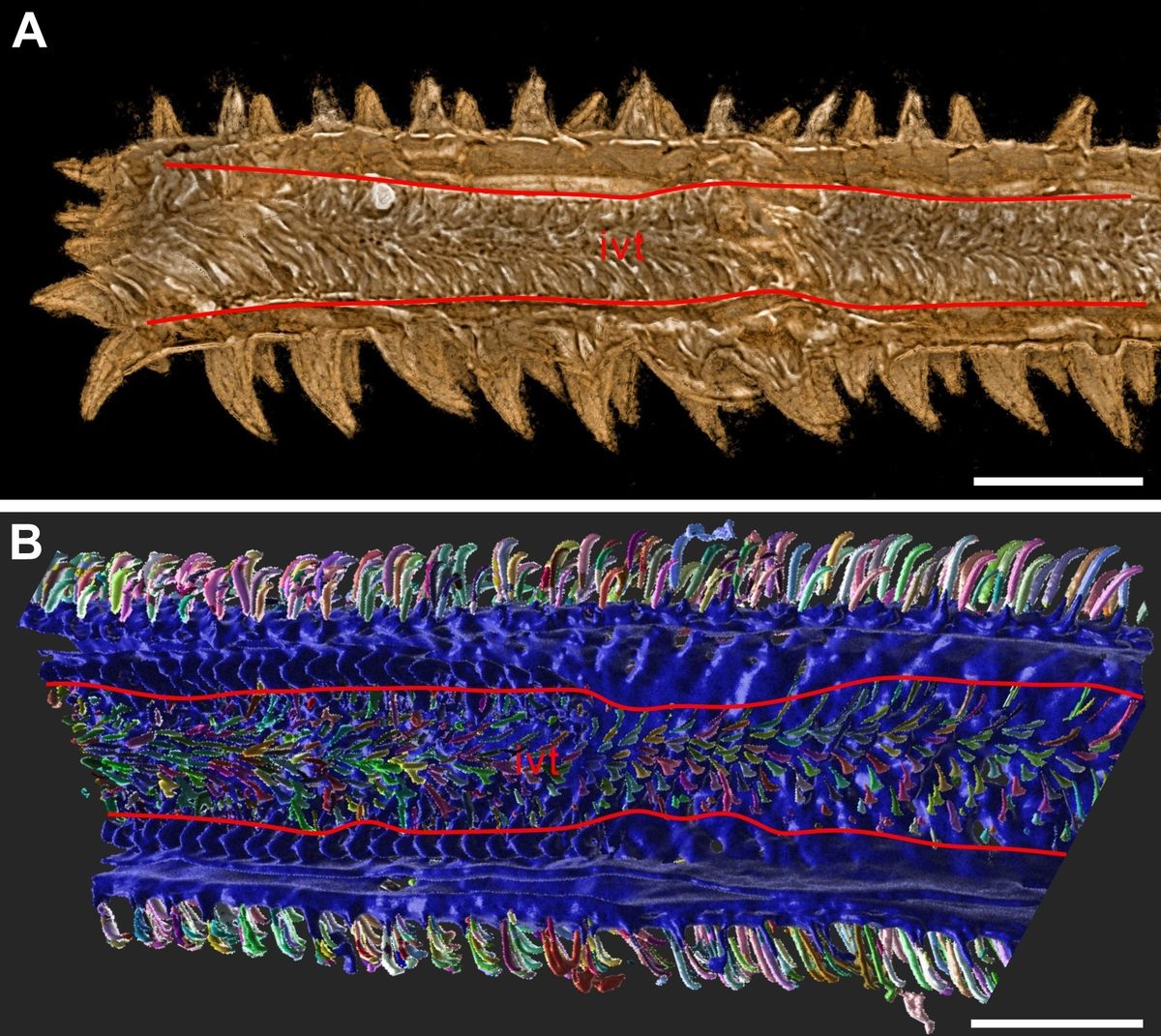

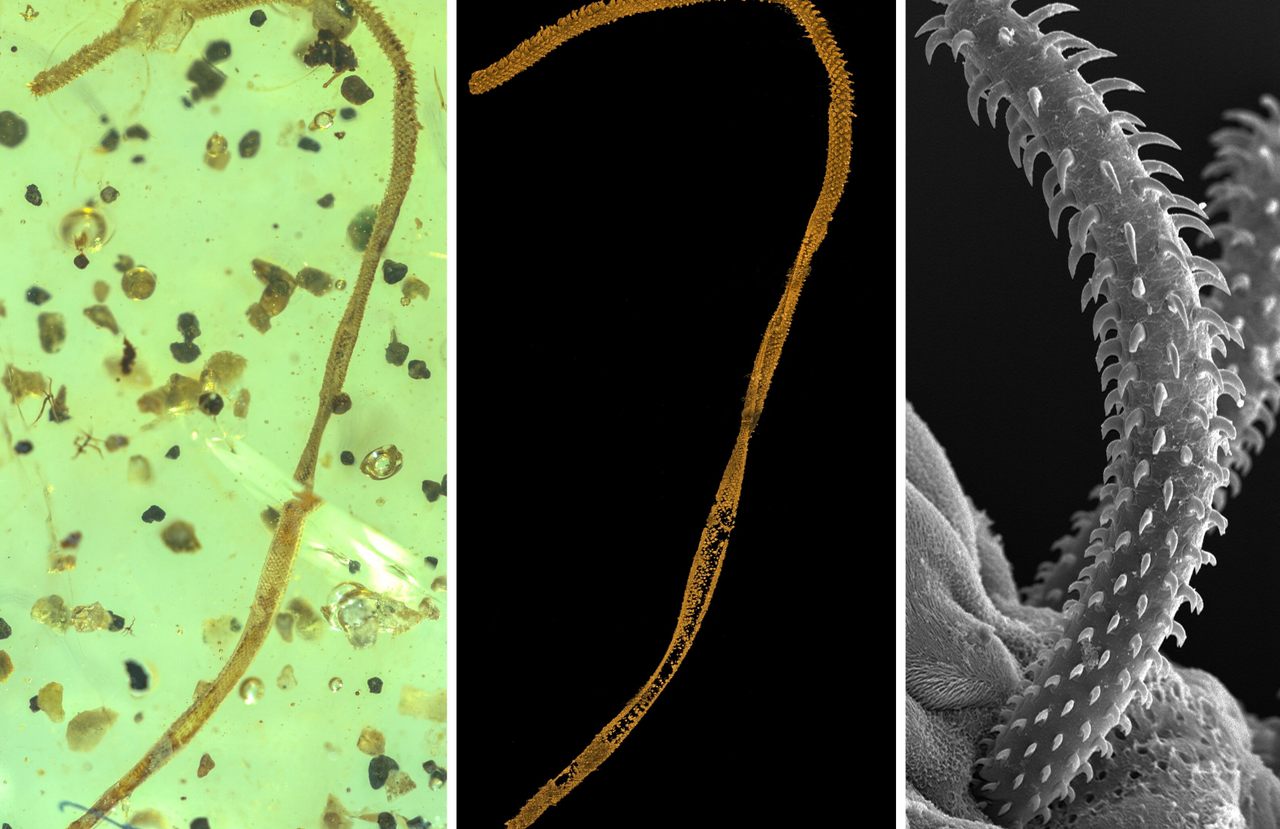

While the roundworm is smooth and flat, the specimen that Luo found had hooks—unlike anything his team had come across before. The discovery, which is specifically a 10-millimeter tentacle of the marine “Trypanorhynch” tapeworm, has shaken up the wider scientific community.

“I’d never predicted you could find an isolated tapeworm in amber,” says Alexander Vargas, a palaeontologist at the University of Chile. “It’s a very unusual finding. Tapeworms are very soft-bodied endoparasites that live inside of other animals.”

Scientists have discovered traces of tapeworms in fossils before, but never an entire body part. Vargas explains that is due to the near-impossible preservation of their soft body parts throughout the millennia. He says understanding the behavior of such a widespread and resilient group of parasites can provide information on the wider ecosystem.

“Tapeworms have economic importance for the fisheries, certainly medical importance for humans, and they have agricultural importance,” says Vargas. “We know through molecular biology they’ve existed for a long time, but hardly any fossil evidence exists of this.”

Luo similarly believes that the fossil can provide key insights into evolutionary patterns. Today, marine tapeworms are still common—and continue to plague sharks and rays—but they have tentacles that typically are some seven millimeters shorter than the fossilized find. This means that they have shrunk over time.

Yet Luo cannot exactly say why they have gotten smaller. “We can tell very little, as a fossil of a tapeworm is so rare,” he says. “We need to discover more fossils to be able to draw conclusions.”

Produced by tree resin, amber is a vital source of information for geologists and palaeontologists. The sticky resin traps insects and small animals, and then, with time, turns into a hardened fossil.

The sample came from an important amber deposit in Kachin, Myanmar. The tapeworm is a type that only infects sea creatures, yet was found with bits of plants grown on land and sand grains, suggesting the tree was close to a beach.

While Kachin today is landlocked and mountainous, the area in the mid-Cretaceous period wouldn’t have looked exactly the same. “Kachin was an island close to the equator, very different to where it is located today,” explains Luo.

The study notes that the hypothesis as to how the marine tapeworm ended up in amber is “still speculative, and the truth may be far beyond our imagination.” But Luo is encouraged to look for more “bizarre” fossils in the Kachin amber, to further aid our understanding of evolutionary patterns. As the study concludes, “No matter how unlikely the preservation of this tapeworm in amber, our study highlights that amber has the potential to capture unexpected life details in deep time.”

Luo adds, “The climate is changing, and many endangered species are going to become extinct, so studying [past] organisms can help us know more about the future.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook