The Life and Death of the ‘Floating City’ of Manaus

To some, this Brazilian neighborhood was a tropical Venice. To others, it was a slum on the water.

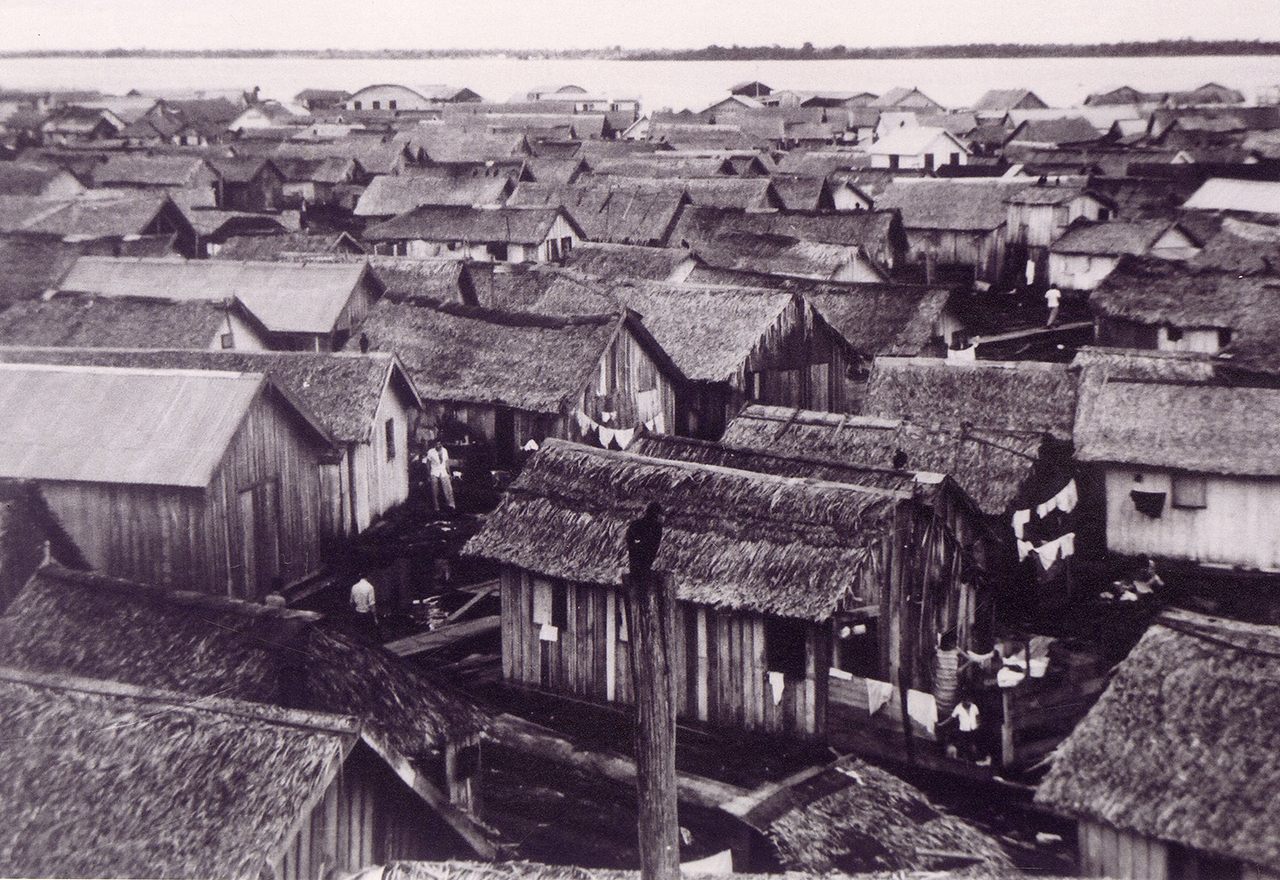

For more than 40 years, Manaus, the largest city in the Brazilian Amazon, had a neighborhood that floated on the river. Located near the Meeting of the Waters, the Floating City was a labyrinthine maze of houses, churches, shops, bars, and restaurants, connected through precarious streets made of wood planks. At its peak, it had around 2,000 bobbing houses built on top of trunks, and a population of more than 11,000 people.

If it hadn’t been destroyed, the Floating City could have become one of the modern icons of the Amazon. Tourists and visitors loved it. It was the subject of features in national and international magazines, where it was often compared to Venice. National Geographic ran a story about it in 1962. And some of the scenes of the Oscar-nominated movie That Man From Rio were shot there. “It was the most vital neighborhood of Manaus,” says Milton Hatoum, a writer from the city, in Portuguese.

However, underneath this layer of fascination was a certain romanticizing of poverty. Most of the residents of the Floating City were low-income families. Sex work and heavy alcohol consumption abounded. And as in most poor districts of Brazil today, there was a lack of basic amenities, such as sanitation and running water.

The story of the Floating City, like the story of the city of Manaus, is closely related to the Rubber Boom. Rubber is made from latex, which is extracted from an Amazonian tree called Hevea brasiliensis. Unlike cotton or sugarcane, rubber trees could not be grown in large plantations at the time, so native trees were the only source of latex. From the end of the 19th century until the first decade of the 20th, virtually all the rubber in the world came from the Amazon forest.

The Rubber Boom made Manaus one of the wealthiest cities in Brazil. Despite its remote location, surrounded by thousands of miles of dense rainforest, Manaus was one of the first cities in the country to have street lighting. Luxurious local buildings, including the Teatro Amazonas, were built around this time.

But it all ended in the 1910s, after the English were able to smuggle seeds and successfully breed a rubber tree that could be grown in plantations. This allowed them to create their own rubber farms in their Asian colonies, causing the collapse of the Brazilian rubber industry.

When the industry collapsed, many of the poor people that worked in the forest collecting rubber moved to Manaus. Some of them decided to build floating houses on the river using the same materials and techniques that they used in the forest.

“The poor people who wanted to remain close to downtown began to realize that living in a floating city was much more interesting for them than living in more distant areas,” says Leno Barata, a historian who wrote his doctoral thesis on the Floating City, in Portuguese. “And living on the river also had other advantages, such as not paying rent or city taxes.”

Initially there were only a handful of disconnected floating houses. But the number rapidly increased after World War II, following a temporary return of the Rubber Boom. With the Japanese occupation of Malaysia, the United States and the Allied Forces were cut off from their rubber supply and turned to Brazil for help. As a result, tens of thousands of Brazilians, mostly from the poor Northeast region, were sent to the Amazon region to relaunch the rubber industry. When the war ended, many of these “rubber soldiers,” as they became known, ended up in Manaus.

“After World War II, in the 1950s, the number of floating houses begins to increase substantially and ends up becoming what became known as the Floating City,” explains Barata.

Many residents had jobs connected to the river. Barata says that living in the Floating City was extremely convenient for fishermen, but also for merchants who bought and sold forest goods, such as nuts, fruits, medicinal plants, and even crocodile skins. Sellers coming from forest communities could bring all these goods and unload them directly onto the floating platforms. This made their job easier, as it saved them from having to carry their haul all the way to the shops. Consequently, merchants in the Floating City received a better price on those products than inland retailers, a fact that generated some resentment among the latter.

As is the case with many long-gone communities, the collective memory of the Floating City is difficult to untangle. Some people remember the neighborhood fondly, while others only recall the more unsavory elements of life on the river. Both positive and negative recollections can suffer from common tropes and stigmas about poverty, but it’s important to remember that the lived realities of the residents of the Floating City were far more complex.

“It was a slum!” says Renato Chamma, a local retailer whose family has owned several shops in the area since the 1920s, in Portuguese. Chamma, who is nearly 90 years old, recalls the floating neighborhood as dangerous and unhealthy, a place full of bars and brothels.

Renato’s nephew Bosco Chamma, who was a child in the late 1950s, says his mother didn’t allow him and his siblings to go to the Floating City, but he sometimes disobeyed her in order to fish. He remembers that on one of those occasions he fell into the water and almost drowned. Drownings of children were relatively common there, as the newspapers of the time attest. For residents from more affluent neighborhoods, stories like Bosco’s only added to the perception of the Floating City as a place of peril.

But not everyone remembers the Floating City in such a negative light. Hatoum, the writer, used to go there as a child with his grandfather. According to him, the people were poor, but they had dignity. He describes the place as vibrant, cheerful, and boisterous, with men and women dressed in colorful clothes singing and playing guitar.

“Sometimes, when it rained or the wind blew, the walkways and the houses built on trunks oscillated, giving one the impression of being traveling down the river,” Hatoum says.

The demolition of the Floating City took place in the second half of the 1960s. The state governor argued that the houses were unsafe and the area was rife with urban and health problems. But there were other interests at play. In 1964, Brazil had suffered a military coup and the new government, aiming to strengthen the northern borders of the country, had a strong interest in economically developing the Amazon region. To do this, they boosted what was then a budding plan to create a Free Economic Zone in Manaus. Through a tax exemption program, the goal was to persuade companies to build their factories there.

The river played an important role in this plan. Because Manaus has almost no road connections with the rest of the country, manufactured goods were shipped along the Amazon River toward the Atlantic Ocean. And the Floating City, with its hundreds of houses by the harbor, was an unpleasant inconvenience. So around that time, some of the lucky residents were relocated to nearby neighborhoods where they were offered houses, and others just left. Then, the floating houses were torn down.

In a way, the Free Economic Zone plan, which is still in force, was a success. It created thousands of jobs and brought money and prosperity back to the city. The city’s population boomed, from around 200,000 people in the 1960s to more than two million today. But along with these gains, there were also losses. Manaus turned into an industrial city. The river, creeks, and water streams became polluted. Illegal settlements mushroomed in the fringes of the city, driving an uncontrolled urban expansion that destroys large patches of rainforest and persists to this day.

Hatoum notes that the end of the Floating City coincided with this radical change in the essence of Manaus. “The Floating City was part of a Manaus that lived in harmony with the river and the environment,” he says. “Its destruction was symbolic because it also broke the link between the urban and natural worlds.”

In the place where the Floating City used to be, there is now a large city market and a harbor, with small passenger and freight boats coming and going. There are no signs left of the “floating slum” that the Chamma family recalls, or the vibrant atmosphere described in Hatoum’s novels. The Floating City only lives now in their memories, small pieces of a larger and more complicated puzzle.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook