Britain’s Most Famous 1700s Sailor Spent 4 Years Disguised as a Man

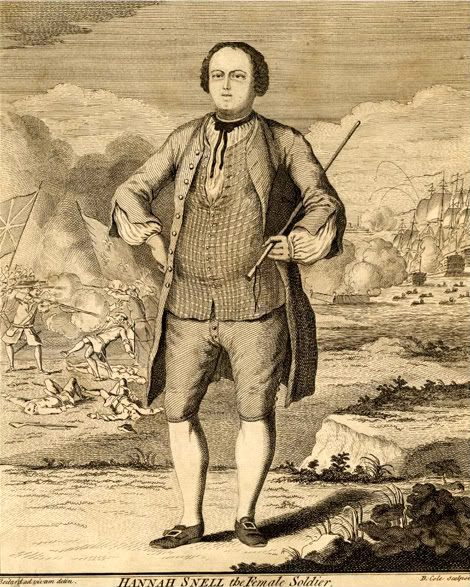

After sailing across much of the world, Hannah Snell starred in a one-woman show and became the subject of a bestselling biography.

In 1747, when she was 22, Hannah Snell left home in search of her missing husband. Instead, she found fame. Over the next five years, she became a sailor and a fighter, all while posing as a man. When Snell returned home and revealed her true gender, far from paying a price for deceit, she became an instant celebrity across Britain.

Snell grew up in landlocked Worcester, England, the daughter of a dyer who had nine children. By the time she was 17, her parents had died, and she had moved to London, to the house of an older sister. It was in the big city that she met James Summs, a Dutch sailor, and married him.

Summs, it seems, was a scoundrel. Even after he had married Snell, he “not only kept criminal Company with other Women of the basest Characters, but also made away with her Things, in Order to support his Luxury, and the daily Expences of his Whores,” as Snell’s biographer would write.

These aren’t exactly the characteristics one looks for in a life partner. The most irresponsible thing that Summs did, though, was abandon Hannah when she was seven months pregnant. Snell gave birth without her husband.

Not long after she was born, Snell’s daughter died, and Hannah left London. She was looking for Summs. At least, that’s the explanation she’d give later. Perhaps it was natural that she would look for him by sailing the world on a British naval ship — her husband had been a sailor, after all. But maybe she was just looking for money and adventure. Whatever her reasons, she disguised herself as a man and started using her brother-in-law’s name, James Gray. As James, she made her way to Portsmouth, on the southern coast of England, joined the military, and was soon headed south.

In the mid-18th century, the British military was a tough place to work; at times press gangs would forcibly “recruit” men into service. The navy, in particular, could be harsh, with disease, food shortages and unwilling recruits making life on the sea difficult. But the army also gave people with few economic prospects the chance to make more money and, sometimes, travel the world.

Snell suffered all the usual hardships and joys of sea. There were storms, and rations ran short, but she made it further from England than she would have been able to almost any other way. She sailed around the tip of Africa, participated in a brief attack against Mauritius, and ended up in India, where her regiment was part of a battle to claim Pondicherry, in South India, from the French. She was wounded—in the groin—and somehow even that didn’t mean that her true gender was discovered.

In the biography that Robert Walker wrote, after her return, there are hints that she wasn’t entirely passing as a man, though. Snell wasn’t the only woman to sneak into the navy in the 18th century, and the fact that few of them were discovered is “very revealing of the low incidence of bathing among the seafarers, either on deck or in the sea,” Andrew Lambert, a professor of naval history, writes for the BBC. But Snell’s shipmates did notice that she never shaved her face and would tease her about it.

She pushed back. She was too young to have a beard, she told them, and anyway, she would wager with any of them that she was in fact a man and give them proof. Apparently it worked well enough that she made it back to England without ever being outed as a woman.

Back in the mother country, though, after she’d been paid the last of the wages that were due to her, she finally confessed her secret to her shipmates. After they’d collected their pay, she proposed that they go out for one last hurrah, and then, finally, “she discovered herself to the whole Company which caused a universal Surprise amongst them all,” Walker writes.

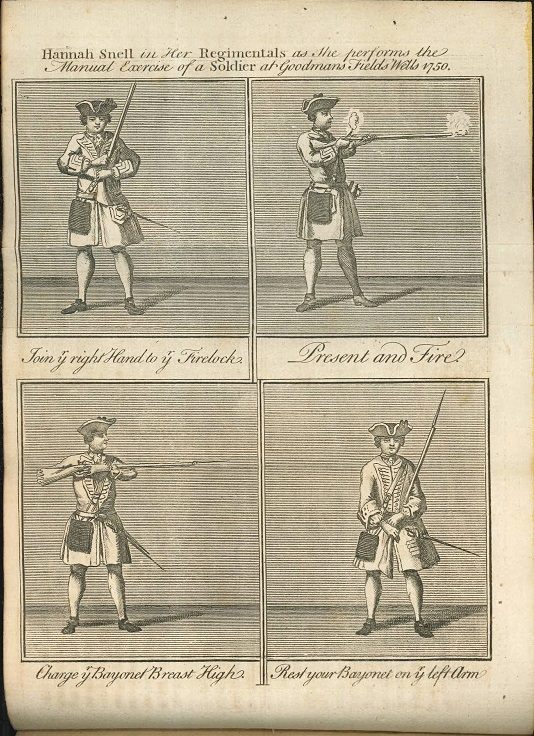

Far from being ostracized, though, Snell became a marvel. Her shipmates encouraged her to apply for a pension, based on the wounds she’d received in India. With her secret out, the story of the female soldier started spreading quickly through London and then the rest of England. She soon became the star of her own stage show, where she’d dress in uniform, recount her adventures and demonstrate military drills and songs. She also sold the rights to her story to Walker, and the book that he wrote based on her account became a bestseller.

That account, The Female Soldier, Or, The Surprising Life and Adventures of Hannah Snell, is the source of much of what’s known about Snell. But how much was true? She was being sold as an unconventional and brave heroine, and it’s easy to imagine that her publisher wasn’t above exaggerating the truth if it made for a better story.

Accordingly, there were parts of the original account that may not be true. The Female Soldier includes an interlude in another regiment before Snell’s sent to sea; it’s likely that was a fabrication. The extent of her wounds, too, may have been overstated. But in a more recent biography, Hannah Snell: The Secret Life of a Female Marine, Matthew Stephens sought to check the claims of Walker’s account against available primary sources. And, he writes, “I was able to demonstrate that the apparently outlandish biography published in 1750 was accurate in many of its claims.” Hannah Snell was the real deal.

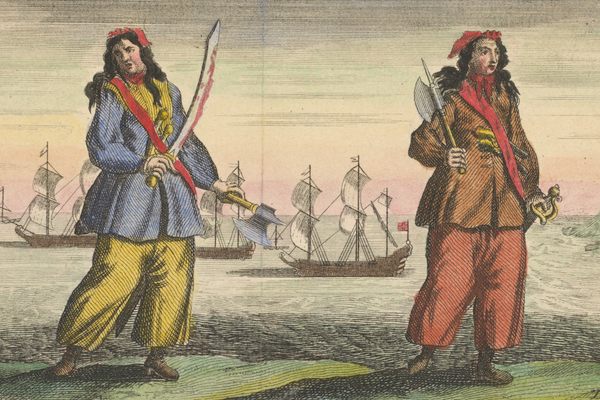

![Anne Bonny and Mary Read were both "convicted of piracy at a Court of Vice Admiralty [and] held at St. Jago de la Vega on the Island of Jamaica, 28th November 1720," according to the inscription accompanying this 1724 Benjamin Cole engraving from <em>A General History of the Pyrates</em>, by Daniel Defoe and Charles Johnson.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/5_kDHgENxQkc0QzZuPs_kICvmEP5JNCV8bcXDI7m5Do/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy81NDQ0ZGNiMi1m/YzRkLTQ4YjUtYTVh/MC0xYzU2ZDliOTY0/YjY1NGNkMWI4MWEw/OTExMDM5ZTZfQW5u/ZSBCb25ueSBhbmQg/TWFyeSBSZWFkIC0g/RmVtYWxlIFBpcmF0/ZXMgaW4gMTgwMHMu/anBn.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook