How the Victorian Fern-Hunting Craze Led To Adventure, Romance, and Crime

“Pteridomania”—an obsession with ferns—gripped the era’s amateur botanists.

Hunters will go to any length to track down their prey. Τhey will cross ridges and climb mountains, risk life and limb, outwit adversaries… even when the prey in question is a very, very stationary fern.

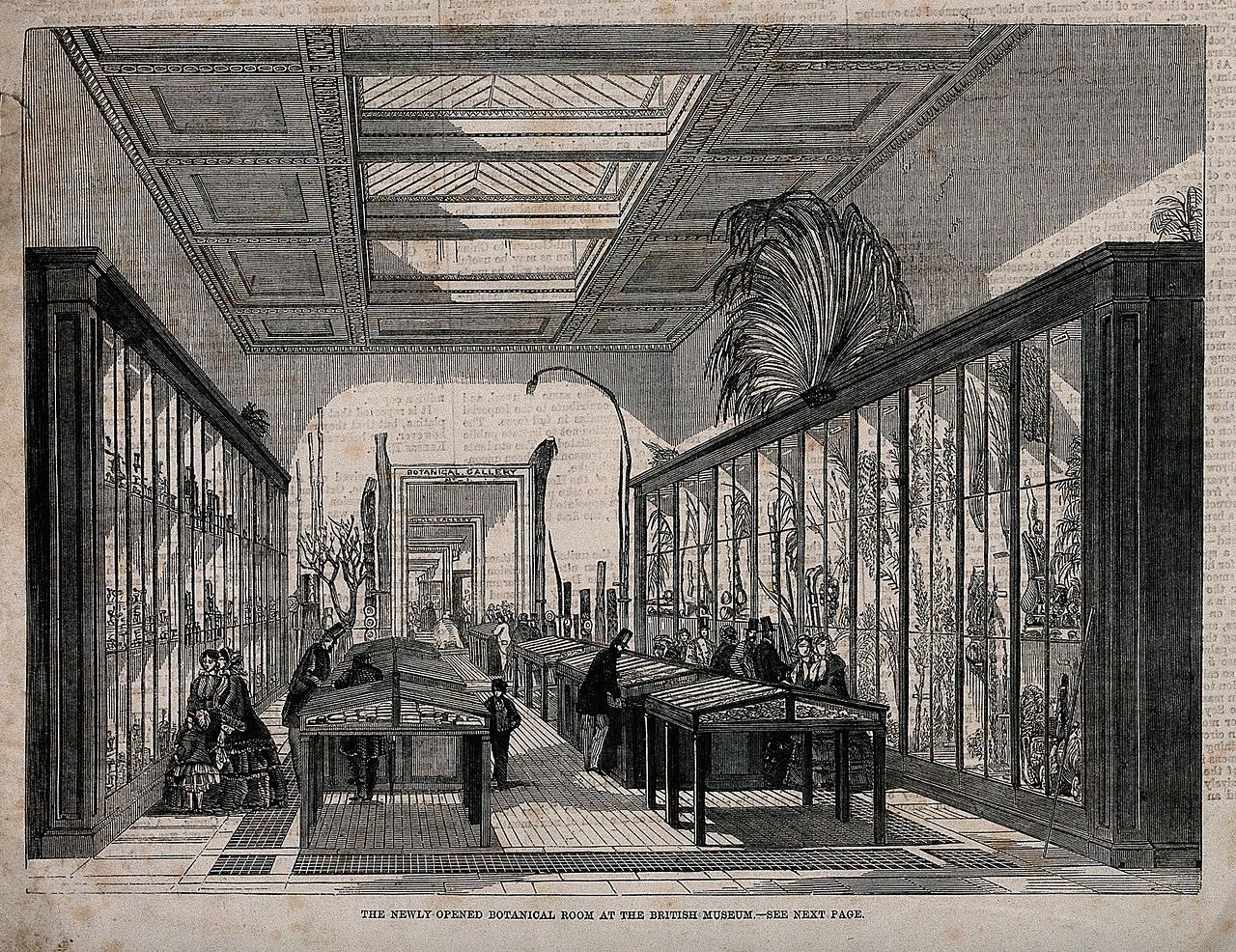

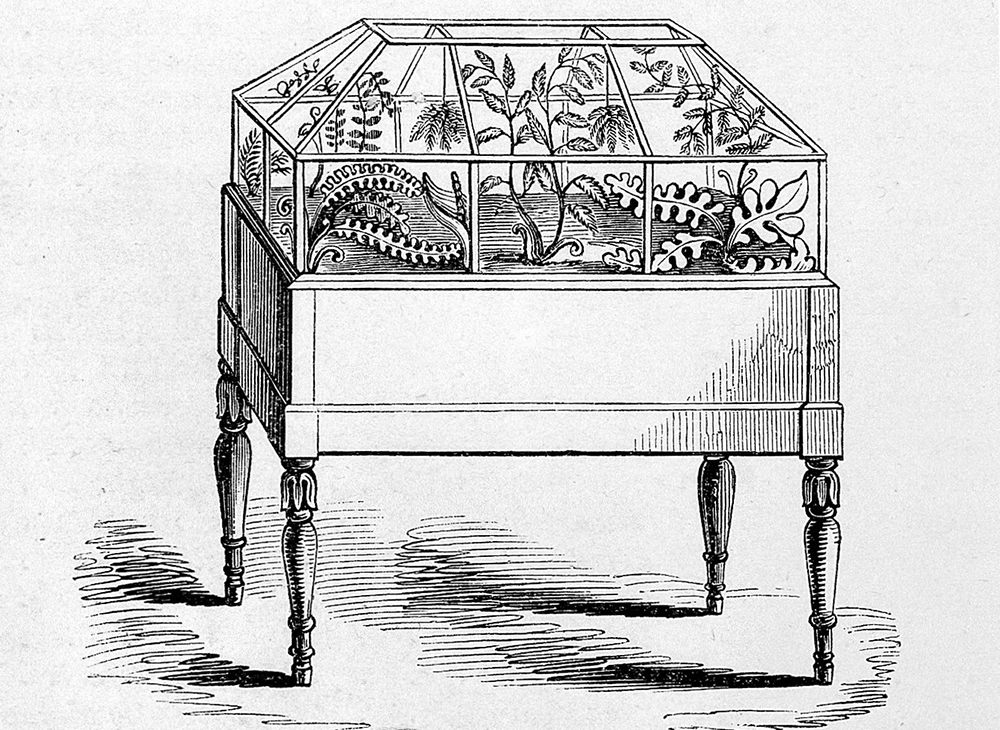

In the 19th century, Victorians on both sides of the Atlantic came down with a severe case of “fern fever”: a craze for all things related to the humble yet ancient plant. It began in 1829, when British surgeon and explorer Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward invented the Wardian case, a glass contraption that kept exotic plants alive in foggy England. His invention allowed botanist George Loddiges to build the world’s largest hothouse in East London, which included a fern nursery.

Even though the plant was already associated with fairies, magic and the more primeval aspects of nature, Loddiges knew that he needed to hype ferns even further in order to attract visitors to his hothouse. So he spread the rumor that fern collecting showed intelligence and improved both virility and mental health. Soon, his neighbor, the famed botanist Edward Newman, published A History of British Ferns, a very well-received book which supported Loddiges’ claims.

We’ll never know if Newman was a true fern enthusiasts or if he was caught up in Loddiges’ rhetoric. In any case, his claims caught on. People started buying and cultivating the rarest specimens they could find, placing them inside increasingly elaborate hothouses. From the start, fern collecting was one of very few hobbies to transcend class barriers: miners and farmers were as likely as aristocrats and scientists to be avid collectors. Indeed, the aristocracy encouraged the poor and the mentally ill to take up the ennobling hobby, and thus elevate themselves.

Newman’s book became a bestseller, as did Thomas Moore’s The Ferns of Great Britain and Ireland. These were far from the only treatises on the subject: between 240 and 400 books on ferns were published at the time. The art of “nature printing”—a process which uses the actual plant to produce its image—was pioneered by Henry Riley Bradbury so that an actual fern specimen could be used in the book plates; in this way, the illustrations could be as accurate as possible.

Soon, the fascination evolved into a craze. People started printing fern motifs on everything: dresses, tea sets, visiting cards, fans, christening presents, custard cream biscuits, even tombstones. Glass, textiles, pottery, and wood were brimming with fern designs. Iron gates, chandeliers, and fire grates were built to resemble the plant’s fronds and leaves. Live ferns hang over dining tables and even inside theaters. Wardian cases filled with ferns were found in every house that could afford them; gardens and orangeries were replaced with ferneries. In 1869, ferns took over the orchestra box in the London Prince of Wales theater, forcing musicians to perform among plants, decorative rocks, and water jets.

The press of the era waxed lyrical about the orchestra box redesign: “The space formally occupied by the band is now converted into a grotto and fernery, intended, with fountains and jets of water, to cool the atmosphere between the acts, and by an ingenious looking glass arrangement to exhibit an interminably multiplied reflection of tiny crystal rills, which will leap and sparkle in the light through a multitude of leafy labyrinths constructed out of tangles masses of choice ferns most artistically disposed.” We can imagine the musicians themselves were less enthusiastic.

Of course, it would not be the Victorian era if some did not condemn the hobby as frivolous—Charles Kingsley, who coined the very term pteridomania, was among the critics. Yet a great many Londoners of all social ranks joined fern hunting societies en masse and subscribed to periodicals, which they read while drinking tea from cups adorned with fern patterns. They would then visit the great ferneries, such as Devon’s Bicton Park—a place filled with gothic grottos, the better to evoke the fern’s primordial mysteries. (It is, after all, a species that has existed since the age of the dinosaurs.)

Their devotion was such that researcher Peter D. A. Boyd likened the fern craze to an actual cult. Perhaps it was a bit of a paradox for the famously uptight Victorians to drown themselves in a plant long connected to female sexuality—but then, this was a quite paradoxical era.

Since the fern was not easy to cultivate, even with Wardian cases at hand, prices soon skyrocketed. After all, there were only 40 types of ferns in the English countryside, and collectors needed more. A non-British specimen could cost up to the Victorian equivalent of 1,000 pounds. Professional fern hunters wrote accounts of scouring the West Indies, Panama and Honduras for a never-seen-before fern. If you could not afford to sponsor a scientific expedition to South America or Asia, there was always the notorious underworld to turn to: crimewaves of fern-stealing plagued the countryside for decades.

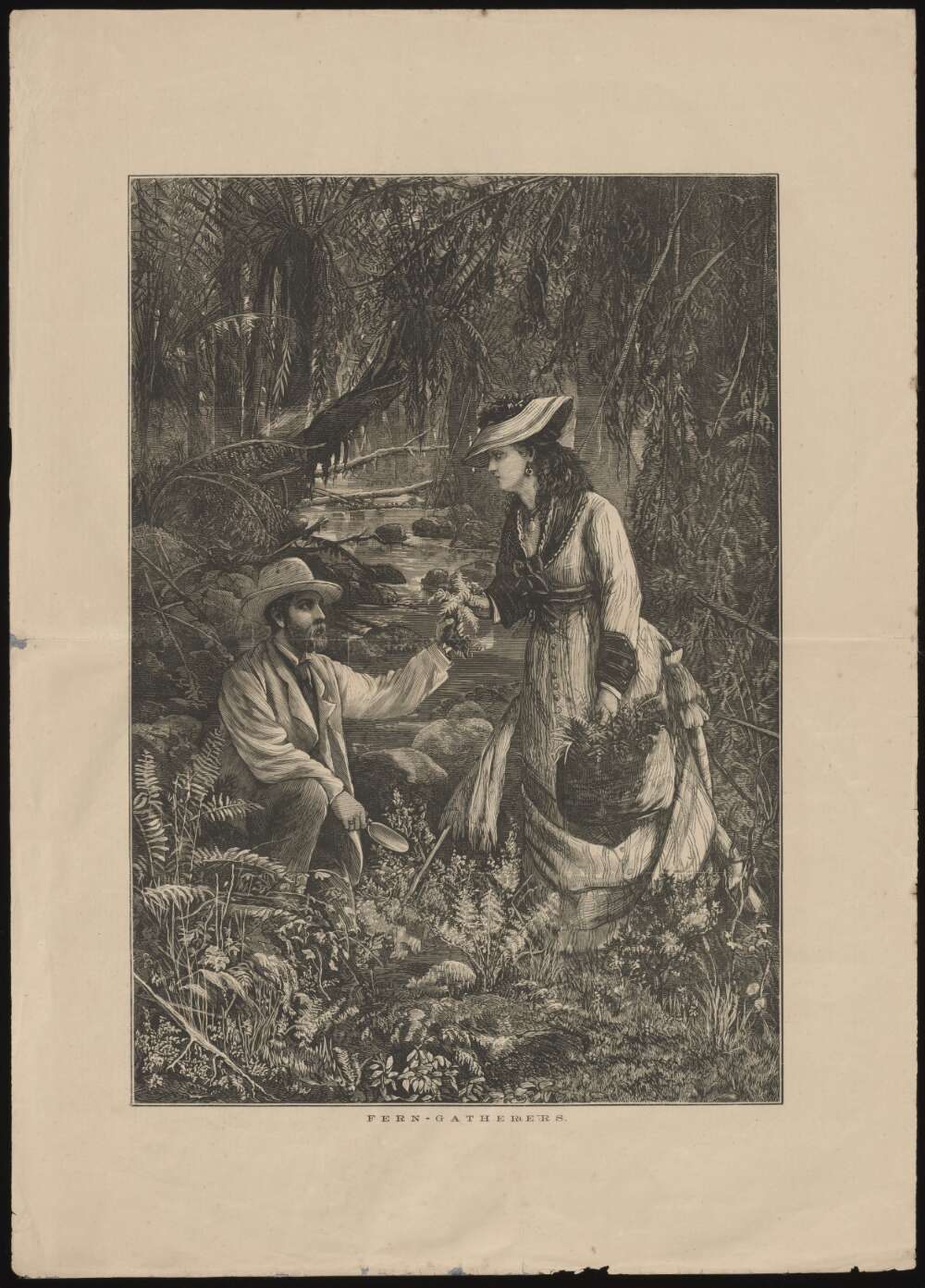

But nothing compared with the ultimate thrill: hunting down the wild fern yourself. Ferns extended an open invitation to adventure. According to Boyd, they grew mostly in the “wilder, wetter, western and northern parts of Britain,” which were just now becoming accessible through better roads and railroads. Since the plant had not been studied and catalogued extensively before, amateur botanists and scientists armed with field guides jumped at the chance to locate a new species for the first time.

At the height of fern fever, even the truly discerning Victorian hostesses abandoned tea parties in favor of organized fern-hunting. Soon, they were organizing daylong woodland expeditions, complete with picnic baskets and competitions for who would find the rarest specimen. Botany was, after all, one of the few avenues open to women who wanted to experience adventure for themselves; it was popular and widespread enough to be deemed an acceptable outdoors activity for the ladies. Indeed, women could even engage into fern hunting unchaperoned, since it was considered an entirely wholesome, healthy, and moral activity.

Novelist and historian Charles Kingsley patronizingly praised the trend, which he named “pteridomania,” as a much healthier preoccupation for young women than “novels and gossip.” After all, he said, it was nicer to come home to specimens of ferns than to endless needlework covering everything in one’s house. Even Charles Dickens turned to ferns to cure his daughter of her perceived apathy, by suggesting she care for a fernery.

Because fern-hunting was fashionable among both sexes and the trips would sometimes end up as all-nighters, romance was known to thrive among amateur botanists. Some of the fern-born romances were even built to last. When California botanists John Gill Lemmon and Sara Plummer were married, they chose to go on a grand plant safari in the Catalina mountains for their honeymoon “instead of the usual stupid and expensive visit to a watering place.” After all, they had already endured a lot in pursuit of their shared passion: in order to get some of the specimens they wanted, they had ended up hiding in makeshift tunnels while Apache war tribes roamed the California hills to weed out white invaders.

The honeymoon, though, topped that experience. The couple ended up wrangling rattlesnakes, chasms, rockslides, fields of cacti, endless heat and cold. They crossed deserts and stayed in the camps horse-thieves had abandoned. They also ran out of supplies, since a trip meant to last for two weeks took them longer than a month. In the end, though, they reached the breathtaking top—a valley they deemed a botanist’s paradise.

Plummer delivered an acclaimed lecture on their adventure and findings, titled “The Ferns of the Pacific Slope.” Arizona’s Mount Lemmon was eventually named after her, the first white woman to reach its top. It remains one of the few mountains named after a woman—not a small feat, considering the couple’s initial findings were touted as the work of “John Gill Lemmon & Wife.”

The Lemmons were not the only Americans to embrace pteridomania. While the craze was subtler there than in Britain, historian Sarah Wittingham has uncovered enough evidence to prove that fern fever gripped the U.S. as well—with, perhaps, a more lasting legacy. The American fern society after all, remains one of the largest in the world.

In the end, the fern craze only declined with the death of Queen Victoria. Up until WWI, people were still going fern hunting, and the great outdoor ferneries were not abandoned until 1918.

Widespread pteridomania meant that some fern varieties such as the Killarney fern were nearly wiped out. But new ones were also created, since plants from all over the world were jammed together in Wardian cases, resulting in interesting cross-breeds. Eventually, ferns were succeeded by orchids as the obsession du jour—but somehow, the beautiful flower never became as influential as the humble fern.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook