Israeli Assassin Sylvia Rafael Never Meant to Be Famous

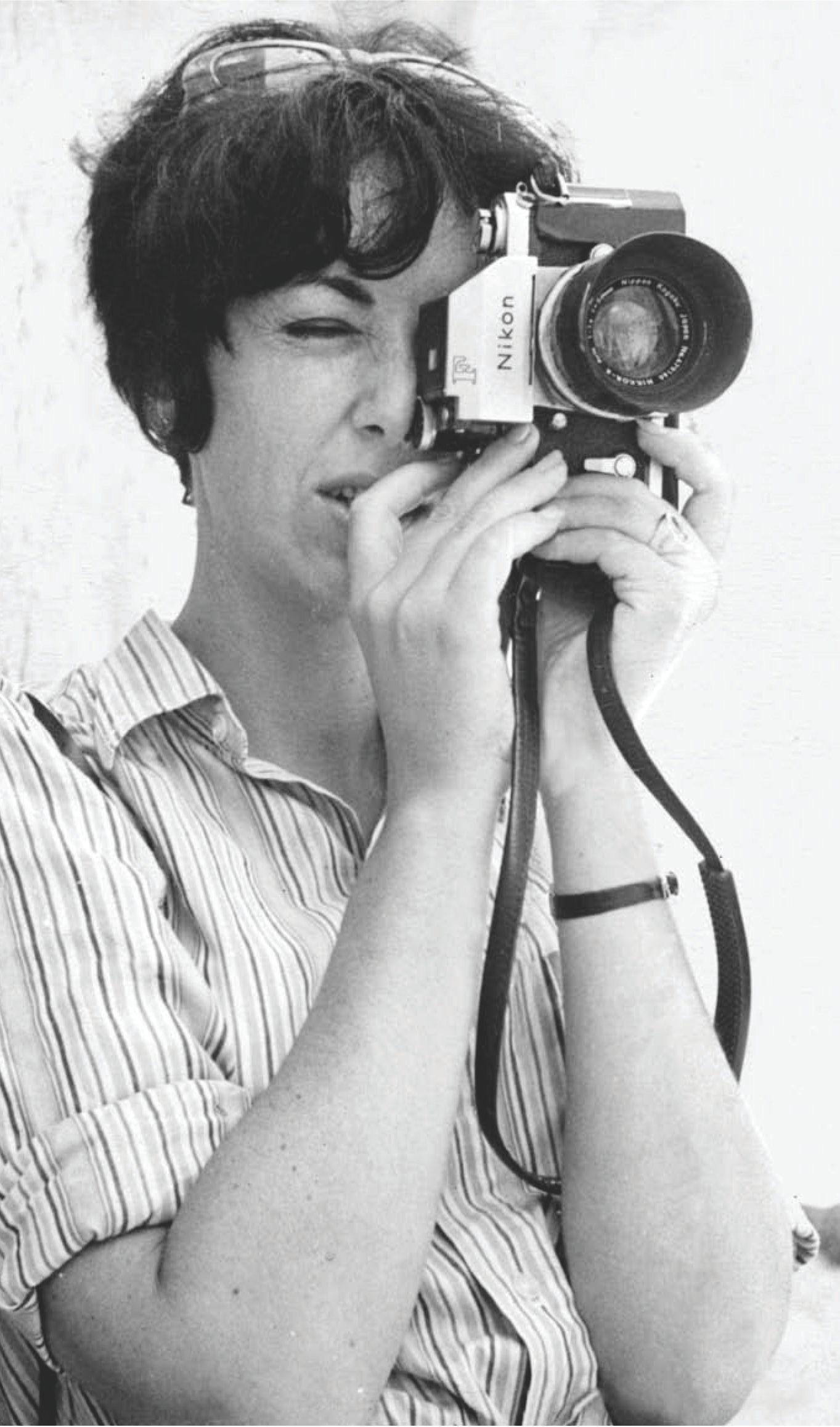

Sylvia Rafael in her identity as Canadian news photographer Patricia Roxenburg. (Photo: Courtesy of Keshet Publishing)

Sylvia Rafael in her identity as Canadian news photographer Patricia Roxenburg. (Photo: Courtesy of Keshet Publishing)

This story is part of series on female assassins. Previously: Which of Gerald Ford’s two would-be assassins was creepier—the Manson girl or the 45-year-old mom?

Sylvia Rafael, an outgoing and beautiful Israeli intelligence operative, didn’t intend to become an assassin. And once she worked as one, she certainly didn’t intend to be known for her work.

Born in South Africa to one Jewish parent and one Christian, all she knew, when she emigrated to Israel in 1959, was that she wanted to do whatever she could to help the still-young country survive and thrive. Initially, that meant working in a kibbutz canning factory and in Tel Aviv as a teacher. But Rafael craved a more challenging career, as her biographers, Ram Oren and Moti Kfer, write in Sylvia Rafael: The Life and Death of a Mossad Spy. And when Mossad, the Israeli analogue to the CIA, recruited her, she jumped at the opportunity.

It’s hard to become famous doing classified work, if you do your job right, and Rafael trained to perfect her spycraft, operating uncover and helping to assassinate a handful of top-level enemies of Israel. But when she was assigned to the team that botched the assassination of Ali Hassan Salameh—the member of Black September who organized the operation at the Munich Olympic Games that ended in the massacre of 11 Israeli athletes—she ended up in Norwegian prison and, suddenly, as one of the most well-known Mossad agents in history.

Rafael grew up in a relatively well-off family in South Africa, and when she moved to Israel, she left behind a man who wanted to marry her and the possibility of a very traditional life. But she believed that Israel was where she belonged. At first, it wasn’t clear to her what she was doing there—whether she was really helping the country. But she gave it time, and three years after she first arrived, she was meeting at a cafe with a Mossad recruiter who thought she might be right for the organization.

Sylvia meets with Israeli writer Ephraim Kishon in the Norwegian prison. (Photo: Courtesy of Keshet Publishing)

Soon, after being trained to wire explosives, conceal her identity, infiltrate buildings, tail targets and perfect the other tools of clandestine combatants, Rafael was in Canada, working to shore up her cover story. In Vancouver, she would become a photojournalist named Patricia Roxenburg; within a few months, as Roxenburg, she moved to Paris, to take a job at a photo agency. As a roving photographer, she was sent abroad to places like French Somaliland (what would become Djibouti) and met well-placed people, like the Jordanian functionary who escorted her through his country, with no idea she was a Mossad spy. With all that travel, it didn’t look so strange when she traveled for her real job, to hostile Arab countries and European cities like Rome, where she would be tasked with finding and following enemies of the Israeli states—and sometimes setting the bombs that killed them.

In 1973, Rafael’s case officer sent her to Norway, as part of a team aiming to assassinate Salameh. Almost from the beginning, though, Rafael felt that something about the mission was off, Oren and Kfer write. She worried, for instance, that one of the team members was an inexperienced operative, on her first mission. And she worried that there was no retreat plan, that the cover stories of the different members of the team did not match up, and that, when they reached the small resort town of Lillehammer, they stuck out from the locals—and made little attempt to conceal their activities.

In Lillehammer, the team identified their target—Ali Hassan Salameh. But, Oren and Kfer write, Rafael worried that they had gotten the wrong man: the man she was tailing didn’t act like a man who had been hunted by Mossad for years and successfully eluded the agency. He was careless; he didn’t take the sort of precautions she imagined Salameh would. But, regardless of her doubts, the team was convinced this was Salameh, and they shot him.

It turned out, though, that Rafael’s worries were right. The man they shot was not Salameh, and the lack of coherent cover stories and a retreat plan left the team exposed. Rafael and her colleagues were detained and arrested and Rafael was eventually sentenced to more than five years in prison, for accessory to murder.

After the incident at Lillehammer, Rafael quit her job at Mossad. She had lost respect for her superiors and colleagues, who had pushed to kill someone even though there were signs they had the wrong man. She returned to Israel—but with the idea that she would soon be back in Norway. During her trial and imprisonment, she had fallen in love with her lawyer. They were married in South Africa and, eventually, moved to Oslo—once her new husband was able to convince his government to let her back into the country. It was tricky: Rafael was now one of the world’s most infamous intelligence agents—even though (as far as we know) she never worked as a spy or assassin again.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook