The New Vonnegut Museum Could Only Have Ever Been in Indianapolis

The author had a love-hate relationship with his hometown.

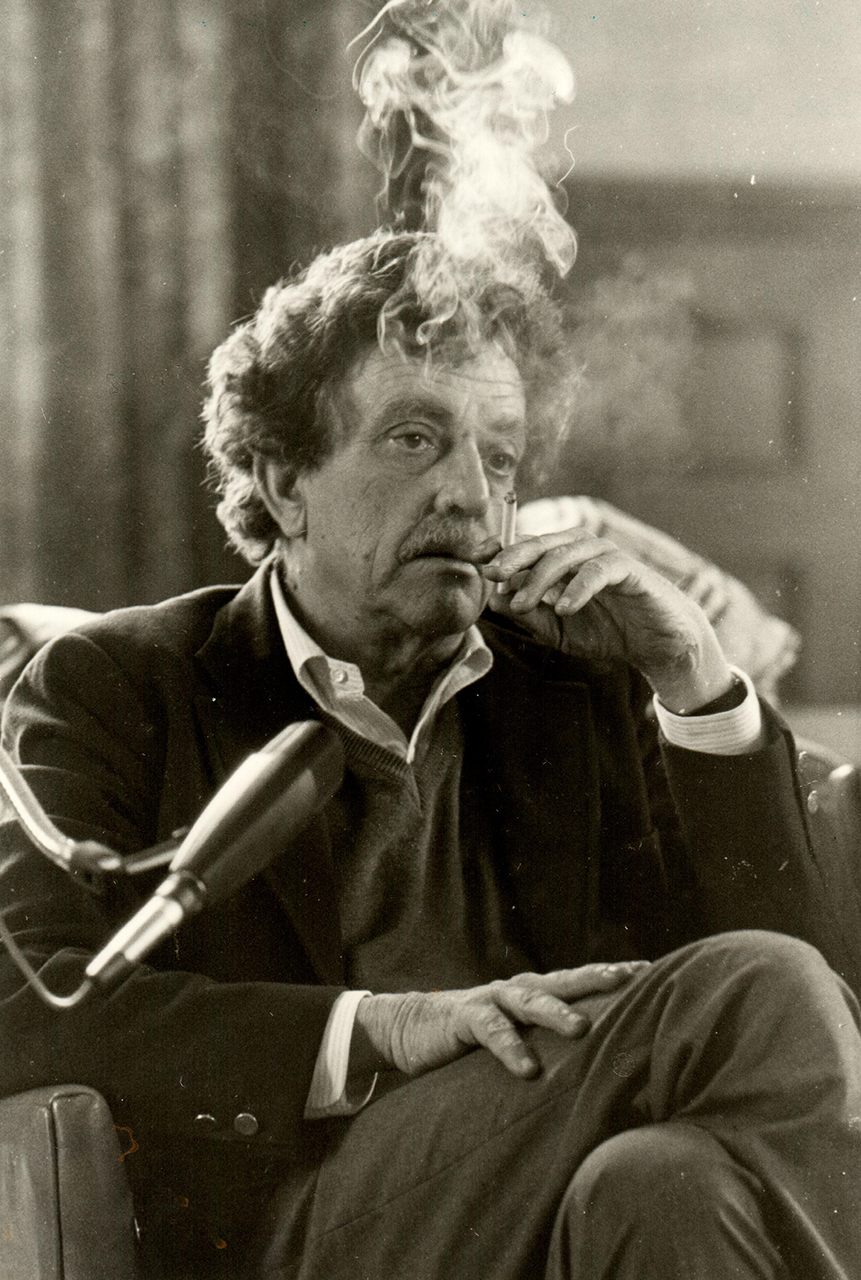

Kurt Vonnegut’s typewriter, Pall Malls, and Purple Heart are boxed and ready to move. Julia Whitehead, founder and CEO of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library, and her team have been keeping these and other artifacts safe while working from cafes, home offices, and a small pop-up shop at the Circle Center Mall. The museum honoring the author’s legacy has spent this year living in limbo, awaiting funding for relocation to a permanent building in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Whitehead conceived the idea for a Vonnegut museum in November of 2008, a year and a half after the author’s death. The physical museum opened in a donated storefront in 2011, displaying items donated by friends or on loan from the Vonnegut family, but has been homeless since January 2019. Charging through a fundraising campaign this spring, the determined grassroots organization recently announced it has secured $1.5 million in donations and will move forward with the purchase of a new building for the museum on Indiana Avenue.

Although Vonnegut left Indianapolis after the Second World War and spent his professional life on the East Coast, Vonnegut’s hometown is the perfect place for the museum. “It should be here because this is the need,” explains Whitehead from a corner of the new space where mocked-up exhibits precede necessary renovations. Planned offerings include Vonnegut’s writing studio, a “Freedom of Expression” exhibit detailing his support of First Amendment rights, and the Slaughterhouse Five exhibit, which will open in November (for Veteran’s Day and Vonnegut’s Birthday). Outside there will be a jazz exhibit, showcasing how the jazz musicians of Indiana Avenue—where the museum is located—impacted Vonnegut. “He is recognized as someone who represents [Indiana] well, someone we can emulate, someone who valued his life growing up here … He thought that his upbringing here in Indianapolis was unique and was special.”

In 1922 Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. was born into wealth and privilege in the Midwestern town. With German roots of Freethinkers and artists, Vonnegut was a fourth-generation Hoosier. His mother was born into the aristocratic Lieber family, owners of the successful Indianapolis Brewing Company. His great-grandfather opened Vonnegut Hardware in 1852, serving Indianapolis for over a century. His father and grandfather, both architects, built many of the city’s landmarks.

Prohibition and the Great Depression devastated the Vonnegut family, but young Kurt didn’t seem to notice. He transferred into the public school system and thrived. He attended Shortridge High School, one of the country’s most distinguished public high schools at the time, and the only one with a daily newspaper. Vonnegut was a contributor and editor of The Echo, along with Madelyn Pugh, who would later become head writer for the I Love Lucy show.

Dan Wakefield, another famed Indianapolis author and longtime friend of Vonnegut is also a Shortridge alum, 10 years Kurt’s junior. When they met in 1963, the year Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle was published,Wakefield was already a fan. In a recent discussion, Wakefield was quick to point out that although they were both working authors at the time, they didn’t talk about any of that. “No, we talked about high school, in fact we always talked about Shortridge somehow.”

Vonnegut’s childhood and adolescence in Indianapolis had a lasting impact on him. In his 1996 graduation speech to Butler University graduates, Vonnegut reminisced, “If I had to do it all over, I would choose to be born again in a hospital in Indianapolis. I would choose to spend my childhood again at 4365 North Illinois Street, about 10 blocks from here, and to again be a product of that city’s public schools.”

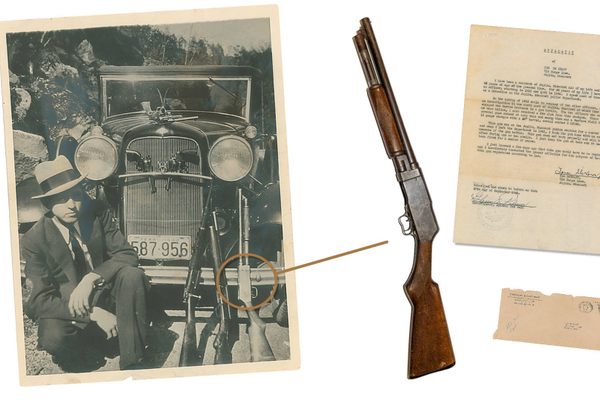

After Shortridge, Vonnegut briefly attended Cornell University before enlisting in the army in 1943. His mother, suffering from depression and subsequent addiction to prescription medication, died by suicide in 1944 over Mother’s Day weekend, just before Kurt shipped out to Europe. During the Battle of the Bulge he was captured by the Germans and taken to Dresden. It was in the safety of an underground slaughterhouse that Vonnegut would miraculously survive the Allied bombings that destroyed the city. He came home with a Purple Heart.

Vonnegut went on to the University of Chicago, followed opportunity East, and eventually settled on Cape Cod with his growing family. His mother “always wanted to live on Cape Cod,” Vonnegut told an interviewer in 1977. “It’s probably very common for sons to try to make their mothers’ impossible dreams come true.” In a 1947 letter to his father Vonnegut offered, “Maybe we’ll come back some day—but not now. I think we’ll do a more honest job of living away from what will always be home.”

Dresden continued to plague Vonnegut as he tried discerning the tragedy on paper. It took many years to finally write about his war experience. He published Slaughterhouse Five, or the Children’s Crusade: a Duty-Dance with Death in 1969, in the midst of the Vietnam War. Many embraced the book, but others banned it and burned it.

This year marks the 50th Anniversary of the novel that hurled Vonnegut into fame. The Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library is observing the golden jubilee with an unprecedented book giveaway, offering every sophomore in Vonnegut’s home state a free copy of Slaughterhouse Five. Writer, historian, and Indianapolis native Gregory Sumner suggests that the true hero of Slaughterhouse Five is not Billy Pilgrim, the main character who spends the pages “unstuck in time,” but Edgar Derby, a middle-aged Indianapolis school teacher also imprisoned by the Germans in Dresden. “He emerges as the leader of the group because he is such a decent person…[he] represents the values of decency, moderation and kindness,” says Sumner. “I would call these Indianapolis values.”

Vonnegut wrote over a dozen novels and many short stories and articles in his life. Indianapolis is represented in many of his works, sometimes under the moniker Midland City. Sumner believes that Vonnegut’s views on his hometown were complex and evolved over time. Vonnegut loved his home and at times hated it, but eventually reconciled with it. In 2007, coincidentally the year of his death at 84, Indianapolis celebrated the Year of Vonnegut, finally paying tribute to its native son. In 2011 he was immortalized in a larger-than-life mural that watches over the streets he stomped as a child. Fellow banned book author and Vonnegut fan, Salman Rushdie, recently spoke at the Night of Vonnegut event. “Death is a great career move,” he joked, poking fun at the city’s timing to embrace Vonnegut as a hometown hero.

Vonnegut was surely stung by rejection, but his heart remained in Indianapolis, once stating, “Indianapolis is what people love about me.” In a 1973 interview with Playboy magazine, Vonnegut was asked if he considered himself a radical. “No,” he answered bluntly, “because everything I believe I was taught in junior civics during the Great Depression—at School 43 in Indianapolis, with full approval of the school board. School 43 wasn’t a radical school. America was an idealistic, pacifist nation at that time.”

The Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library will open for a sneak preview in time for the American Library Association’s Banned Books Week, which begins on September 22. (Within the museum, this event is referred to as Freedom to Read Week. “Freedom to Read Week and Banned Books Week are one and the same,” the museum website reads, “but some folks thought we were celebrating the banning of books!”)

Ultimately, Whitehead wants the museum to be something Kurt would love. Vonnegut “always wanted the best for Indianapolis and tried to vocalize that,” she says. “He always wanted Indianapolis to be more progressive, more inclusive and [for] organizations like public schools and public libraries to be well funded, partly because he had such a great experience here.”

Have a favorite Vonnegut book or quote? Tell us about it over in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook