Mariners Today Still Use a Math Genius’ 1802 Navigation Guide

A Salem ship in 1802 (Image: M.F. Corne)

There are certain books that become a center of gravity for people, a guide to life and to work. For many people, that’s the Bible. For American mariners, over the last 200 years, that book has been Bowditch.

“Bowditch is the Gray’s Anatomy for navigation,” says Gerard Clifford, a marine safety office at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. “I went to the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, and when my section all lined up at the bookstore, we got bombarded with books. By far the heaviest and largest book we received was Bowditch.”

Clifford has a picture he keeps, of a officer re-enlisting in the navy. In the ceremony, the officer has a choice of swearing his oath on a Bible or other meaningful tome. “He has his hand on a copy of Bowditch.”

Officially, the book is titled The American Practical Navigator, but it’s more commonly called Bowditch after Nathaniel Bowditch, the young prodigy who wrote the original 1802 edition. For two centuries, copies of this book have settled themselves onto the bridges of ships circling the globe, and helped guide mariners safely from place to place. It has been the foundational text of American shipping, for 213 years, an atypically long reign for a scientific manual.

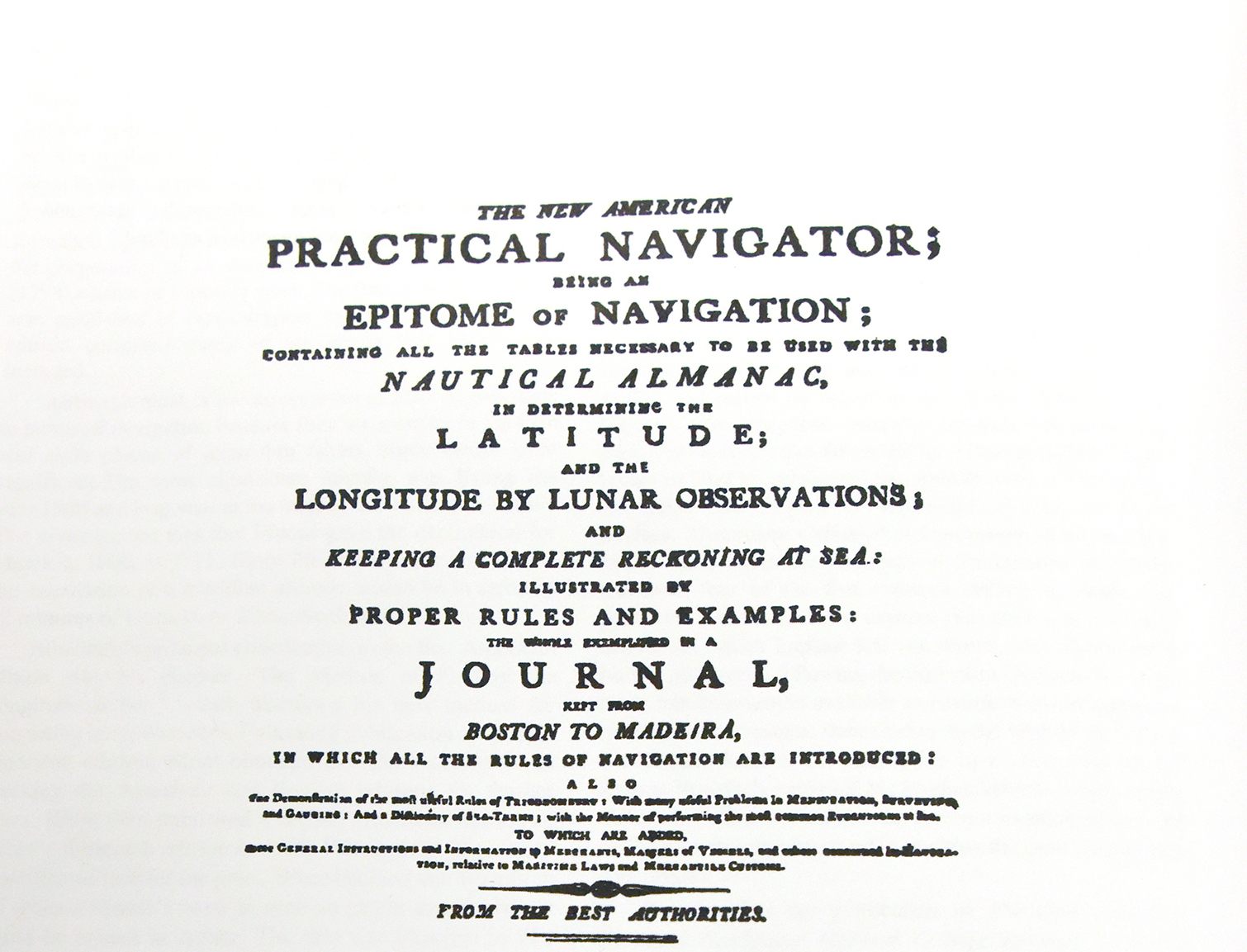

The original frontispiece of Bowditch (Image: NGA)

Nathaniel Bowditch made five sea voyages in his career as a mariner, to ports like Lisbon, Madeira, Manila, Cadiz, Batavia, and Sumatra. His most famous navigational feat came at the end of his last lengthy journey, in 1803. He was sailing back home to Salem, Massachusetts, on a tempestuous Christmas afternoon, where snow and fog whited out visibility and there were few clues to help guide a ship safely through the harbor’s hazards. The safer choice would have been to wait, further from shore, to land when the storm cleared. But Bowditch was sure of his calculations.

He took control of the ship, and kept watching the spot where a light should appear, on Baker’s Island, at the entrance to the harbor. And, then, for just a moment, the snowfall let up, and he saw it. He knew exactly where he was, he kept on course, and he made it safely back to his hometown.

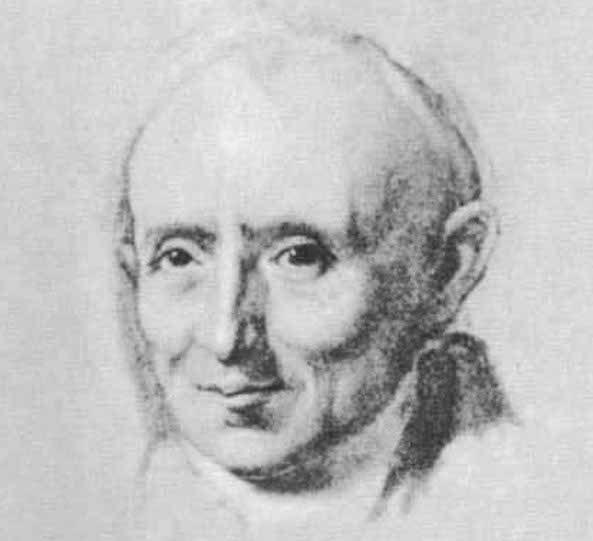

The Bowditch family had lived in Salem for generations by the time Nathaniel was born in 1773, but his father, Habakkuk, had fallen into misfortune, losing two ships and trying to scrape together a living as a cooper, crafting wooden household items like utensils and barrels. When he was 12, Nathaniel started work at a company that outfitted ships, and he learned the art of navigation at 13, from an old sailor.

As a teenager, Bowditch was obsessed with math, and was seen as something of a prodigy on the subject. He taught himself French, Greek, Latin, Spanish and German. When he was 16, he started studying Newton’s Principia and found an error in the famous text. By the time he actually went to sea at 21, he had surveyed the town of Salem, designed a barometer, and put together a decent almanac.

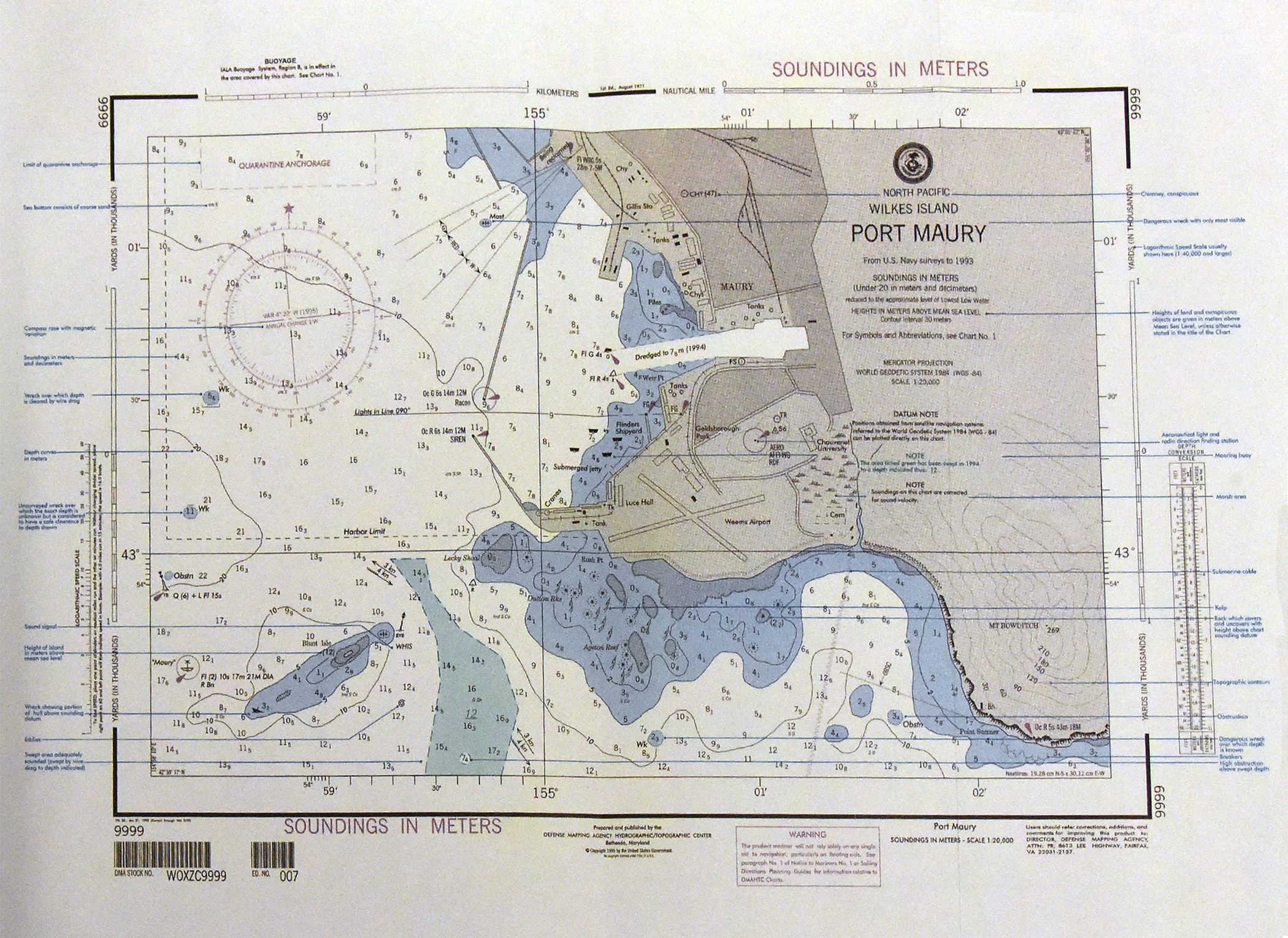

A navigational chart (Image: NGA)

In the 1790s, when Bowditch’s seafaring career began, the most accurate way of determining a ship’s position was through celestial navigation. But to use the stars and moon as a perfect guide required complex mathematics, beyond the skills of most sailors. Instead they used blunter navigational tools and relied on The Practical Navigator, a guide by John Hamilton Moore, a British instructor of navigation.

Bowditch, too, began by relying on this book. But soon he was finding errors in it, and rewriting the book’s most useful tables. He also started working out a simplified way of calculating lunar distances, between the Moon and a star or planet, which could be then be used to determine longitude, even by sailors who were not math geniuses.

Around this same time, a publisher in New England, Edmund Blunt, was looking to update Moore’s Practical Navigator and issue an American edition. He hired Bowditch and other navigational experts to comb through the original text for errors; in that first American edition, published in 1799, Bowditch also contributed a chapter outlining his simplified strategy for determining longitude from lunar distances. For the next American edition, published in 1802, Bowditch made so many corrections and additions to Moore’s work that Blunt released it as an entirely new book: The New American Practical Navigator, by Nathaniel Bowditch.

Nathaniel Bowditch (Image: Gilbert Stuart/Wikimedia)

There’s still a section on celestial navigation in the 2002 edition of Bowditch, the most recent update, although it has shrunk considerably over 200 years. The basic math might be the same, but the details and the precision have improved. It still tells mariners how to move along coastlines and pilot ships, but now has huge sections on radar and other modern tools for getting a ship from one place to another safely.

“Now, when you learn celestial navigation, you get these big sheets of paper, and there are all these factors that go into the formula you use to compute the final position,” says Clifford.

Clifford, along with colleagues at the Coast Guard, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Navy and other parts of the government, is currently working on the book’s next big update, which is scheduled to be published in 2017. Bowditch’s original American publisher, Blunt, kept releasing editions until the U.S. government bought the copyright in 1867 and took over the job of keeping the book’s contents current. These days, it covers a huge swath of modern knowledge: electronic navigation, radio waves, electronic charts, navigational safety, oceanography, meteorology and more—everything that goes into the contemporary art of navigation. This next update will not even be published as a book: the NGA plans on releasing it electronically.

Right now, Clifford and his colleagues are looking to collect ideas about what can and should be updated in Bowditch, from experts across the whole scope of the science that goes into navigation. But even as the guide continues to morph to contain the modern world, the kernel of Nathaniel Bowditch’s work is still there.

“There’s a lot of concern that students new to navigation are becoming too dependent on electronic means of navigation,” says Clifford, “that they’re not looking out the window in front of them, and they’re not verifying their position.”

“The U.S. Navy had dropped celestial navigation from their curriculum, but they’ve reintroduced that now,” he says.”They understand that you have to have that capability as a back up and to confirm electronic navigation.”

Mariners, even in the 21st century, still need to know what they’re seeing if they look up at the stars.

Bowditch, 2002 (Photo: NGA)

![Anne Bonny and Mary Read were both "convicted of piracy at a Court of Vice Admiralty [and] held at St. Jago de la Vega on the Island of Jamaica, 28th November 1720," according to the inscription accompanying this 1724 Benjamin Cole engraving from <em>A General History of the Pyrates</em>, by Daniel Defoe and Charles Johnson.](https://img.atlasobscura.com/5_kDHgENxQkc0QzZuPs_kICvmEP5JNCV8bcXDI7m5Do/rs:fill:600:400:1/g:ce/q:81/sm:1/scp:1/ar:1/aHR0cHM6Ly9hdGxh/cy1kZXYuczMuYW1h/em9uYXdzLmNvbS91/cGxvYWRzL2Fzc2V0/cy81NDQ0ZGNiMi1m/YzRkLTQ4YjUtYTVh/MC0xYzU2ZDliOTY0/YjY1NGNkMWI4MWEw/OTExMDM5ZTZfQW5u/ZSBCb25ueSBhbmQg/TWFyeSBSZWFkIC0g/RmVtYWxlIFBpcmF0/ZXMgaW4gMTgwMHMu/anBn.jpg)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook