Last Century a DJ Saved My Life

New York City’s oldest-school spinners are two phonograph-loving guys named Mike.

If you’re in New York City, and you like to dance, you’ve got a lot of options. A typical night offers everything from punk shows to EDM nights to tango classes to old-school hip hop. It is the city that never sleeps, after all.

But what if you’re really old school—like ragtime-vs-jazz, Ma-Rainey-for-life, beat-anyone-in-a-jitterbug-contest old school? Never fear: there’s someone out there spinning for you, too. Michael Cumella and Mike Haar, New York’s premiere phonograph DJs, both love music from the early 1900s. For decades now, they’ve spent their spare time keeping it alive, one hand-cranked revolution at a time.

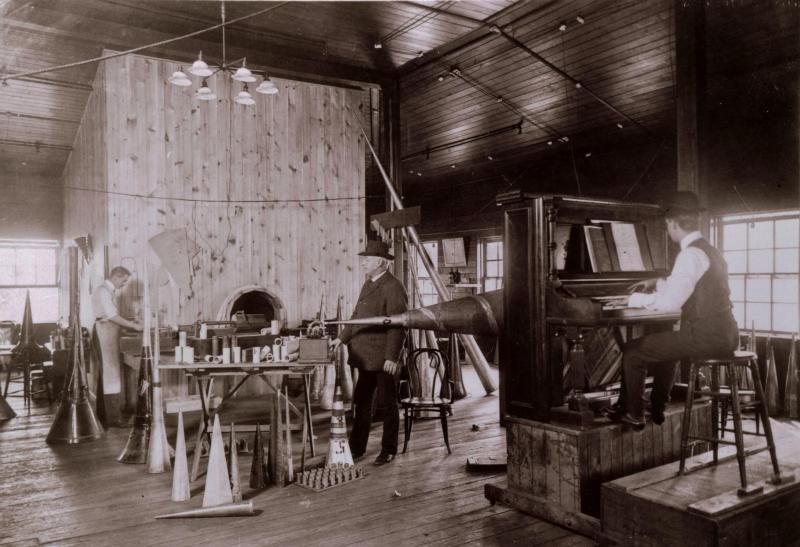

The first three decades of the 20th century saw an explosion of musical experimentation, as ballads and military marches gave way to jazz, blues, country, and early R&B. Although much of this invention was happening live, in dance halls and on vaudeville stages, some of it ended up etched into 78-rpm discs, or “78s.” Fans would buy these and play them in their living rooms, on big-horned phonographs.

Fast forward a century or so, and despite the repeated terraforming of the music technology landscape, one thing hasn’t changed: if you want to listen to a recording from the early 1900s, you pretty much have to do it the old-fashioned way, via a 78 played through a phonograph. Cumella learned this about 30 years ago. “I’ve always collected records, and I wanted to go back farther with music,” he says. “At a certain point, you have to encounter the 78 era. There wasn’t much reissued, so if you’re interested in it, you start to acquire those kinds of records, and the machines that people played them on.”

He was quickly hooked. In 1995, he started spinning 78s on the radio, hosting a show called “The Antique Phonograph Music Program” on WFMU. He did his first live gig soon after, upon request. “Someone contacted me and said, ‘We’re having a party, would you come and DJ with the phonographs?’” he recalls. “I was like, ‘You know what they sound like, right?’” After a few other one-offs, a friend of his encouraged him to get serious: “‘It’s your thing now,’ she told me.” He had some business cards made up, and he now plays live a few times a month, at jazz festivals, record fairs, and weddings.

Phonograph DJing takes dexterity—you’ve got to change the needle (every two songs!), switch out the 78s, and keep the machine cranked. But rather than focusing on traditional DJ calling cards (volume, hipness, smooth transitions), Cumella generally goes for a more interactive experience. He’ll play the music relatively softly, so that people have to come over to see what’s going on. He answers questions, and lets people stick their heads in the horn, like the dog in the classic Victor ad. Sometimes he fails to re-crank the machine, on purpose. “It’ll start to slow down and get lower—deedly-deedly-deeeeeedlllyyyy-deeeeeedddllyyyyyy,” he imitates. “They’re like, ‘What’s going on!’”

Haar, who is almost two decades younger than Cumella, first heard phonograph-era music in a college class on African-American jazz and blues. “The professor was playing all these records from the tens, teens, 20s and 30s, and I was blown away by it,” he says. “It paralleled the energy and excitement and oddity that punk did for me as a teenager… Something about it was so different and raw.” When he came across a phonograph and some 78s in his great-aunt’s closet, his fate was sealed.

Although the two each developed the hobby on their own, they didn’t stay strangers for long—even New York City isn’t big enough for that. “Someone told me, ‘You know, there’s another guy named Michael who actually does the same thing,’” remembers Haar. “We became buddies.” “He’s my bestie,” confirms Cumella. They now perform together, and guest on each other’s radio shows.

Before he found Cumella, Haar practiced his art on his immediate family, playing records for his grandparents and their close friends. When he got more comfortable, he ventured out, bringing his crates and machines to nursing homes in Queens and the Bronx. Reviews were mixed: “Some were amused and some were not amused,” Haar says. “The music that I was playing, it was more like their parents’ music—older, even.”

Such is one burden of the phonograph DJ. Another is more literal: “It’s a heavy profession,” says Haar. The 78s, which were generally printed on shellac, are thicker and more fragile than this era’s vinyl LPs. The horns are huge—each has the circumference of a bicycle wheel. Cumella has custom cases for his go-to phonographs, a Victor and a Columbia, both from 1905. “They were made so well,” he says. “They’ll probably outlive us, and our children, and their children.”

Even if his muscles occasionally complain, Haar, especially, appreciates this physicality. For his day job, as a barber, he uses antique straight razors—“I always wanted to do something professionally that involves tools, and using my hands,” he says. He wears vintage clothing, and sports a center part and a caterpillar mustache. If you ran into him on the street and he told you he was a phonograph DJ, you wouldn’t necessarily be surprised.

When you listen to music on a phonograph, he says, you can almost hear the sheer effort that went into it. “I enjoy the hardship,” he says. “Today, we have thousands of songs on our phones. It’s interesting how slow of a process it was [in those days], and how much one song meant.” Cumella agrees: “When you’re listening to [this music] live, standing in front of the machine, it’s almost physical,” he says. “You can feel the vibrations.”

People will approach them when they’re playing, Haar says, trying to figure it all out: “Is it real? Where is the sound coming from?” From the past, via a couple of conduits named Mike.

Learn more about early recording technology at the Johnson Victrola Museum on Obscura Day, May 6, 2017—or dance to the two Mikes’ phonograph stylings at the official Obscura Day After-Party, held at New York’s oldest club.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook