Colorado’s Pikes Peak Is an Eclipse Hot Spot (for 2045)

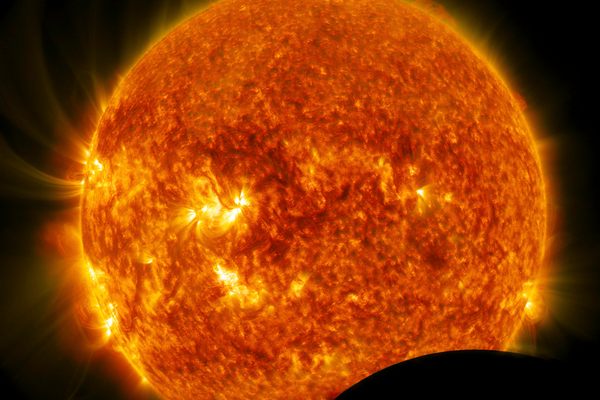

The Mountain West helped put American science on the map during the 1878 total solar eclipse, and it’s the place to be for the next big American eclipse.

Eclipse chasers hope for clear skies, so here’s hoping for a good forecast for Monday, April 8. But if you are the kind of person who likes to plan way ahead, consider coming to the Mountain West in 21 years and four months. Colorado is known for more than 300 days of sunshine, and the August 2045 total eclipse crosses most of the state.

The next meeting of Sun and Moon over the United States parallels the 1878 eclipse, which crossed the Rocky Mountains when Colorado was a brand-new state (the Centennial State was admitted into the Union in 1876) and mountain communities were still populated mostly by silver and gold miners. Studying the eclipse across a young and modernizing America gave our scientists great credibility, as the Colorado author David Baron beautifully accounts in his 2017 book American Eclipse. But it also put Colorado firmly on the map.

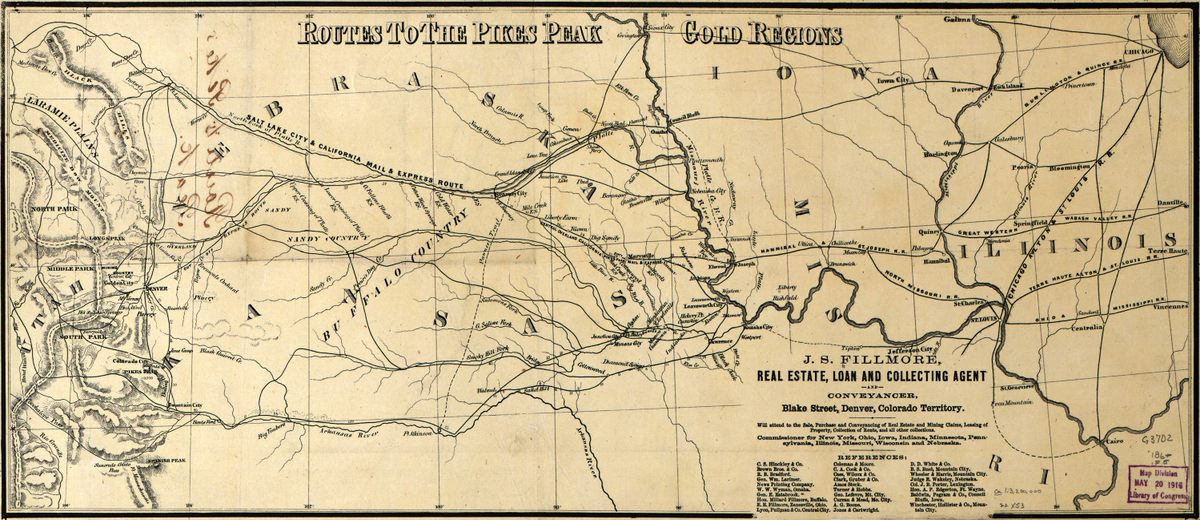

Astronomers calculated that the 1878 eclipse would run down the Rockies, from Wyoming Territory through Colorado and into Texas. Colorado was the best place to visit, because it had the greatest number of established cities. What’s more, Colorado’s clear skies and thin atmosphere (thanks to its high elevation above sea level) would provide a clear view of the inner solar system, helping astronomers determine whether there was a long-hypothesized planet between Mercury and the Sun. The purported planet, nicknamed Vulcan, would only be visible during a solar eclipse—and by 1878 telescopes were powerful enough, and scientific observation was careful enough, to finally find it, if it existed.

Burgeoning railroad towns and mining outposts saw dollar signs in the celestial event; the Pennsylvania Railroad Company even gave professional astronomers half-price train tickets to Denver, via Chicago or St. Louis.

Scientists and tourists fanned out across the Front Range. Some scientists went to Denver, especially the neighborhood of Cherry Creek. Astronomer Asaph Hall, who discovered the moons of Mars in 1877, brought an expedition to the plains town of La Junta.

Tourists from as far as Europe flocked to Garden of the Gods, in Colorado Springs, where tents were erected for shade and people could watch the eclipse after paying a 25-cent admission fee, according to History Colorado.

One group of astronomers from the Naval Observatory and West Point went to the mining town of Central City, and observed the eclipse from the Teller House hotel, which is now a restaurant in a casino town. Astronomers from St. Louis went to Idaho Springs, not far from Central City. Samuel Pierpont Langley, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, led an expedition with his brother John Langley and the meteorologist Cleveland Abbe to the summit of Pikes Peak. People and pack animals trekked 18 miles from the Colorado Springs train station to the mountain summit, hauling equipment that included a five-inch-diameter telescope, which weighed nearly half a ton.

Towering over Colorado Springs at 14,115 feet, the peak promised thin air and few clouds, although the week before the eclipse saw heavy rain, hail, and snow, which covered scientific instruments and rusted the astronomers’ telescopes. All of them suffered from altitude sickness.

But Colorado came through on eclipse day. Walter Spencer, a reporter for The Denver Times, was stationed in Castle Rock, a then-tiny outpost between Colorado Springs and Denver. “Weather splendid for eclipse—clear as hell,” he reported.

The Georgetown Courier reported: “Monday morning the sun rose … in a cloudless sky, and every sign bespoke a genuine Colorado summer day for the great event astronomers had promised.”

As the eclipse approached, scientists trained their instruments toward the Sun. Nobody discovered Vulcan, because it does not exist—but astronomers and interested spectators made detailed observations of things they did see.

My personal favorite account is by James H. Freeman, a 20-year-old shepherd on a small ranch in La Junta, who kept a diary of the events. He wrote that “a thousand eyes are turned on this plain, gazing over my head, and, perhaps, some through powerful glasses are watching me as I write.” He brought his sheep into their fold before the eclipse, and climbed onto the roof of his house, viewing the sun through smoked glass. (Do not do this! Buy eclipse glasses from a reputable vendor.)

“At 3:15 it looks like a new moon at sunset. It is a strange, weird light now and getting dimmer. 3:20. Oh! Oh! What a weird, gloomy sight. 3:26 Total. Oh! What a strangely beautiful scene.

“The darkness passed away almost at once when the first ray came down. One moment it was dark as midnight—the next, as late as midday.

“The chickens stretched their necks curiously as the sky darkened, turned an eye upward, then ran for the roost, stepping high and awkward. Birds chirruped sadly, and the stars came out thickly overhead,” Freeman wrote.

“There was a luminous ring around where the sun ought to have been and the horizon miles away was bright all around, showing the limit of the totality. Then a bright ray shot down and the dark shadow glided swiftly off to the southeast. In a few seconds it disappeared over high ridges 20 miles away. It looked like a black carpet sliding over the plains.

“The clear crystalline atmosphere here, at an altitude of more than 6,000 feet above sea level, could not be improved on. It came to me without cost or invitation.”

From Georgetown to Denver, banks closed, stores shuttered, and people stood in the streets, gawking at the scene.

The Denver Tribune reflected on the event afterward:

“In the presence of so many bright and shining lights of science … THE TRIBUNE cannot let the occasion pass by without complimenting Colorado on the beautiful weather she furnished for the occasion, and the general success which attended the exhibition. It was a notable event in our history.”

The 1878 eclipse put the young state on the map. Twenty years from now, a similar celestial event will once again darken the skies over the best state in the union. Might as well plan ahead.

Wondersky columnist Rebecca Boyle is the author of Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are (January 2024, Random House). She is a featured speaker at Atlas Obscura’s Ecliptic Festival, April 5-8, 2024, in Hot Springs, Ark.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook