The 1700s Plague Cure That Inspired an Uncannily Contemporary Cocktail

An art historian, a culinary researcher, and a Twin Cities distillery teamed up to recreate the herbaceous drink.

When Nicole LaBouff and Emily Beck first decided to create a modern version of plague water, the potent herbal liquor that early-modern Europeans believed could help prevent epidemics, they had no idea how contemporary their experiment would soon prove. It was spring 2018, two years before a novel coronavirus would lead to the worst global pandemic in a century, and LaBouff was looking for a way to illuminate 18th-century French nightlife.

LaBouff is Associate Curator of Textiles at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA), whose holdings include 18th-century period rooms from Paris and Providence, Rhode Island. She wanted to create sensory experiences to bring these rooms to life for a contemporary audience. “What we’re trying to do is get people to understand that real people lived here,” she says. One day she wondered: Why not try booze?

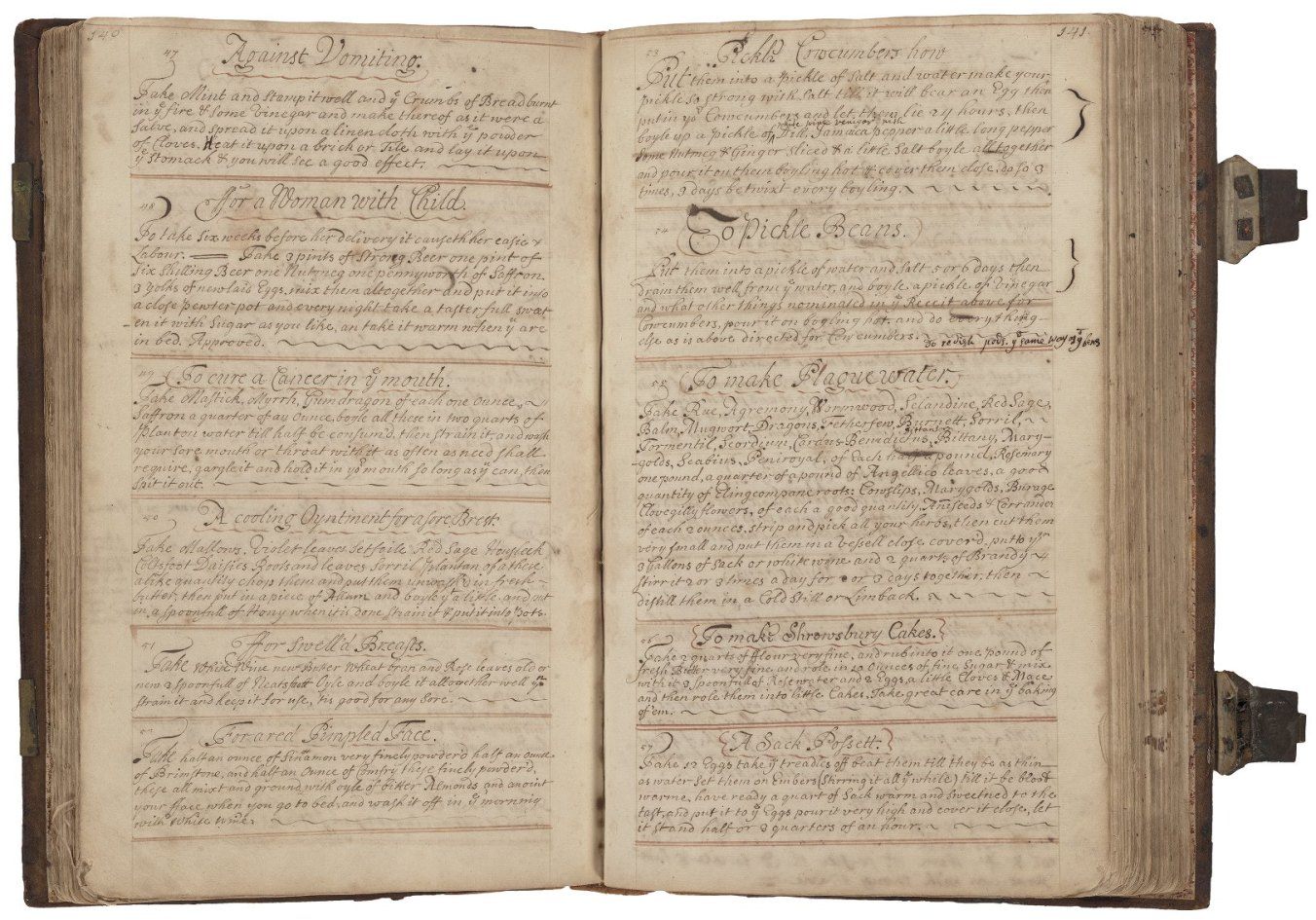

So LaBouff turned to Emily Beck, an Assistant Curator at the University of Minnesota’s Wangensteen Historical Library who specializes in historical recipes. While modern doctors tend to think of food and medicine as distinct categories, for much of human history—and in many cultures today—the two categories were interchangeable. Early-modern European cookbooks were mostly costly, handwritten tomes found in elite households (most people couldn’t read or afford books). They had guides to making everything from poultry to poultices, from pickles to plague water. “I often describe them as early-modern Pinterest, because it’s basically recipes for anything you can think of,” says Beck.

Consisting of dozens of herbs distilled in alcohol, plague waters were a common feature of these cookbooks. Medieval doctors, part of the Galenic medical tradition, believed that illness was caused by imbalanced bodily humors triggered by “miasma,” or foul-smelling air. Aromatics, such as the herbs in plague water, were believed to help counter these smells. A plague outbreak in 1666 England, which killed 750,000 people, reinforced the need for households to be prepared. Even by the 1700s, when boozy nightlife was heating up Parisian parlors, the legacy of regular, catastrophic sickness meant that recipes for plague water shared cookbook pages with more festive intoxicants.

Many early-modern Europeans, says Marissa Nicosia, a Penn State scholar of 17th-century English recipes, made their own plague water in household distilleries, from gardened or foraged herbs. (Nicosia wasn’t involved in the MIA project, but recently did her own research on plague water recipes.) Recipes could call for dozens of different herbs; the one Nicosia recently posted, from 1670s England, called for 27 different herbs, including rue, wormwood, mugwort, and something called “dragons.” The recipe on which Beck and LaBouff hoped to base their recreation, meanwhile, called for two dozen herbs and herbal infusions, including green walnuts, elderflower, juniper berries, and “Venice treacle,” an early-modern apothecary cure that included viper’s flesh, skink bellies, and opium.

When Beck and LaBouff set out to replicate plague water recipes, they realized that—unlike early-modern Europeans—they could not try this at home. Home distillation is illegal in the United States, and the daunting list of aromatics wasn’t available in the grocery store.

The historians turned to Dan Oskey, founder of Tattersall Distilling in Minneapolis, to recreate the drinks. Oskey, LaBouff, and Beck combed hundreds of historical recipes, settling on several sweeter, more straightforward options, such as pear ratafia, a fruity cordial, and milk punch, a rum-based brew that had fortified transatlantic sailors. Plague water was the most complicated. When Oskey encountered the recipe’s old-fashioned language, he says, his first reaction was, “What the heck does that mean?”

So Oskey and the two scholars embarked on some culinary detective work. First, they had to figure out which herbs the recipe actually meant. “The name might have changed over time, or it might have been a region-specific name from 400 years ago,” says Oskey. Then, they struggled with historical recipes’ notorious imprecision. “We were trying to determine, What’s a handful? Was it fresh? Was it dry?” he says. A more serious roadblock: Some of the ingredients were unavailable, not approved for human consumption, or even poisonous. A 1667 recipe from The London Distiller, for example, called for ambergris, an aromatic substance that comes from whale intestines. A 1670s recipe, from a home English Cookery and Medicine Book, called for pennyroyal, an English herb since shown to cause liver damage.

“There was a lot of improvising,” says LaBouff. After months of trial-and-error—dropping the Venice treacle, and substituting the herb lepidium for unethical ambergris—modern-day plague water was born. The drink was aromatic and bitter, a “big, fresh, green herb flavor,” says Oskey. “It has this kind of mushroomy, umami quality to it,” says LaBouff. The team unveiled the elixir at the Tattersall Cocktail Room at a March 2019 fete. Guests milled around to music, snacking on early-modern English pastries and sipping milk punch. At the time, the reality of pandemic seemed so distantly historical that the event’s starring cocktail was whimsically dubbed “Plague Party.”

A year later, Tattersall’s cavernous Cocktail Room is empty. The distillery has shut its public-facing operations in accordance with social-distancing guidelines, the result of a pandemic that past party guests likely couldn’t have imagined. Tattersall’s distilling rooms, however, are frenetic. Every morning for the past few weeks, while many Twin Cities residents shelter at home, employees enter the premises, keeping a six-foot distance from one another. They work 12-hour days to make a modern version of plague water: hand sanitizer.

Tattersall has converted its facility to make isopropyl alcohol, rather than the ethanol of drinking liquor, for first responders, homeless shelters, and other public services. It’s part of a public-spirited attempt by distilleries around the U.S. to augment the country’s dire lack of medical supplies. The demand for hand sanitizer is so high, says Oskey, that even after producing more than 9,000 gallons of the stuff in the past week, the company still faces a backlog. “Everybody needs it and wants it,” says Oskey. “We can’t keep up.”

There’s an irony, of course, to Tattersall’s transition from artisanal plague water to mass-produced hand sanitizer. While drinking the herbal alcohol likely didn’t help prevent plague, the medieval apothecaries who connected distilling to public health were onto something. They just didn’t realize that rather than drinking alcohol, they could have been using it to clean their hands.

LaBouff finds a kind of comfort in the sudden, uncanny relevance of her research. “It does get you to forge this empathetic connection with people in the past,” she says. “Being in the midst of it now, you experience it in a whole new way.”

“It’s almost an attempt to try to take control over a situation that doesn’t make sense,” Beck says of historic plague water recipes. She sees similar meaning-making attempts today, as COVID-19 throws daily routines, and deeper certainties, into question. “Can I still go to the grocery store? Do I have to quarantine my mail?” Beck asks. “It’s so unclear to people.”

In the midst of this uncertainty, we turn, as our ancestors have always done, to what is familiar and fortifying: food and booze. While both the MIA and public health officials advise against heavy drinking—excessive alcohol use can weaken the immune system and increase vulnerability to COVID-19—plague water recipes reveal that, in times of social crisis, humans have long sought a stiff drink. If you do find yourself having a cocktail while sheltering in place, you’re in good company. “Drinking throughout the day?” says LaBouff. “People were doing that in the 18th century, too.”

Plague Water-Inspired Cocktail

From Tattersall Distilling and the Minneapolis Institute of Art

• 1 ounce Green Chartreuse (substitute for Plague Water)

• ½ ounce Becherovka (substitute for Aqua Mirabilis)

• ½ ounce pineapple juice

• ¼ ounce honey sage syrup

• ¼ ounce lemon juice

Honey Sage Syrup: In a saucepan, add 1 cup honey, 1 cup water, and 1 tablespoon fresh sage roughly chopped. Cook on medium, stirring until simmering. Reduce heat and simmer five minutes. Cool and strain.

Combine Honey Sage Syrup and remaining ingredients with ice. Shake. Strain. Pour in coupe glass. Garnish with lime wheel.

You can see the MIA and Tattersall’s full selection of historical recipes online at Alcohol’s Empire, and more historical recipes at the Wangensteen Historical Library. Public service providers in Minnesota can request Tattersall hand sanitizer through the All Hands site.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook