The Bittersweet Thrill of Iceboating in a Warming World

For hundreds of years, sailors have zipped across frozen lakes and rivers—but now chances are fewer and farther between.

James “T” Thieler has spent his whole life chasing thrills in sailboats. He first got his feet wet near Atlantic City, New Jersey, where he commanded his parents’ beat-up Hobie 16 catamaran through choppy water under the blistering sun. The most rousing part was “torturing” the boat, he says, trying to jump massive waves and drive the bucking thing high up on the shore. Thieler planned to spend adulthood floating around the Caribbean and working on boats, but by 1998, he found himself in Maine, instead. Up there, winters had sharp teeth, but sailors were undeterred. When there was little open water (also known as “soft water”) to be found, a cohort of them took to rivers and ponds in light, sleek, sail-driven crafts that could coast across the ice with runners or skates affixed to their hulls. It was extreme—fast, cold, and odd—and that piqued his interest. “I thought, ‘Boy, that looks really next-level,’” he says.

Thieler was hooked the instant he got out on the ice. “I picked up an old, cheap iceboat, sailed it 50 feet, and that was the end of that,” he says. Now he is a champion racer and the commodore emeritus for the New England Ice Yacht Association (NEIYA).

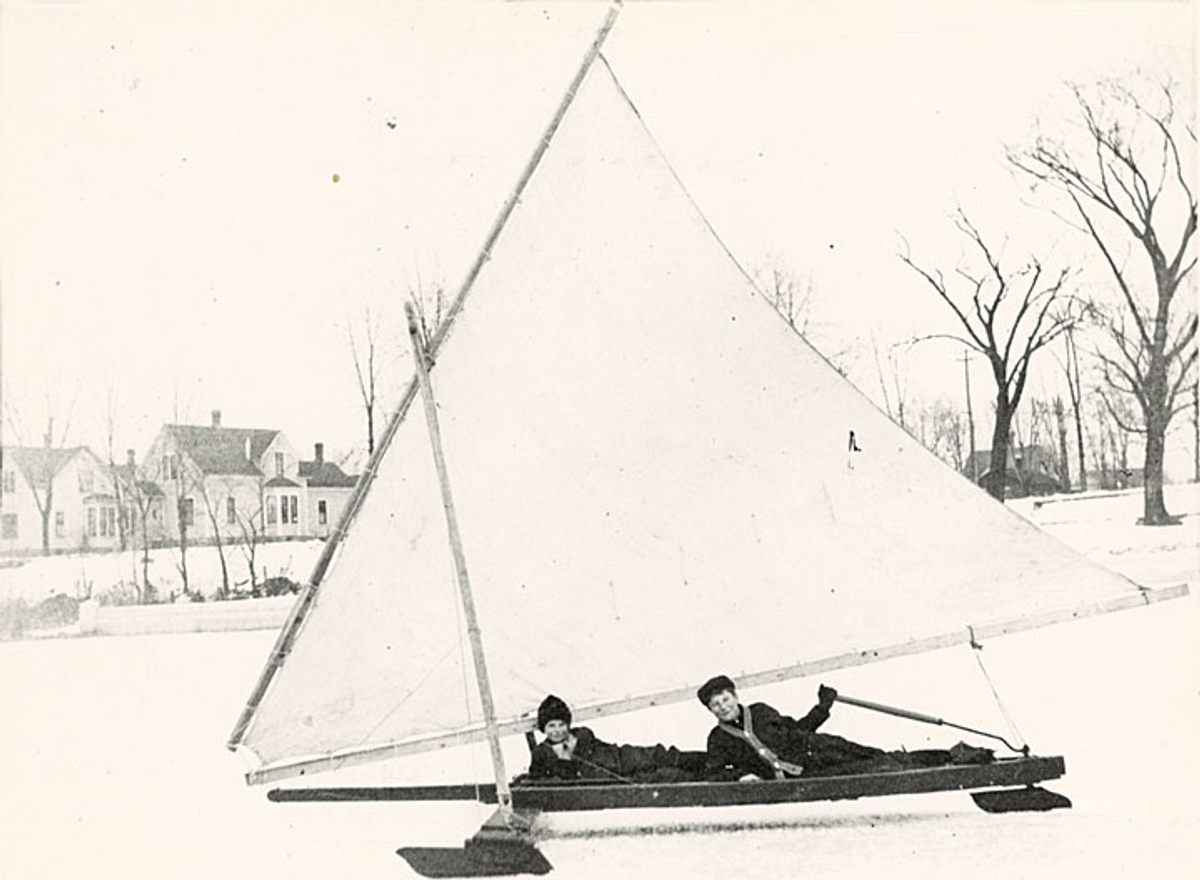

The speed of iceboating is what really drew Thieler in. Heavy, single-hulled sailboats on water typically top out around 8 to 12 knots. “It’s about as fast as you go in a traffic jam on I-95,” Thieler says. Though some sophisticated (and expensive) multi-hulled vessels can push 30 knots, Thieler adds, iceboating is something else entirely: An iceboat can easily exceed 80 miles an hour, and often goes much, much faster. “A hundred miles an hour is not unreasonable under perfect conditions,” says John Stanton, commodore of the NEIYA. Like bobsledders—kindred cold-weather spirits—iceboat racers often start from a standstill and then sprint across the frozen water. When the wind catches the sail, they launch themselves in, and then, depending on the type of boat, may lie flat on their backs, contorting themselves into the most aerodynamic shape they can manage. The whooshing wind, the morning cold—Thieler felt flooded, and he couldn’t get enough. “It knocked me on my butt,” he says. “I can’t really think of any thrill that comes close.”

Iceboating, also known as ice yachting, has been enchanting and thrilling people for several hundred years. It began in Europe in the 1600s, and landed in New York by the 18th century, Hudson Valley magazine reports. By the last quarter of the 1800s, the frozen Hudson River, which separates New York and New Jersey, was stippled with boats. In December 1875, the New York Daily Herald declared that iceboating “has assumed a dignity among the outdoor recreations of the year second to none,” and predicted that, since clubs devoted to the sport were popping up so rapidly across the country, “there is great promise of its future.”

Ice yachting gave dedicated sailors—including Franklin D. Roosevelt, who helmed an ice yacht called Hawk—something to do in the winter, and the spectacle captivated onlookers, too. “It is an inspiring sight to see a fleet of 20 or more ice yachts, with their white sails sparkling in the frosty air, circling around each other with the speed of the wind,” The New York Times reported in 1896, adding that when the breeze was generous, the boats outstripped the trains on the tracks flanking the river. “This was the fastest mode of transportation for a long time,” Stanton says.

For both racers and enthusiasts, iceboating is still exhilarating. “Every day is an adventure in that I see different areas that I wouldn’t normally get to see,” says Kate Morrone, a New Hampshire–based ice cruiser who first sailed a hand-me-down iceboat that her father had raced in the Finger Lakes of New York in the 1970s and 1980s. “And the ice is beautiful in all its different forms.”

But now, many winters are feeling more like springs—and that leaves winter sports, from iceboating to backyard skating to skijoring, on unsteady ground. In a warming world, where ice is constantly cracking, calving, melting, and giving way, how long much longer does iceboating have?

Data compiled by the National Snow and Ice Data Center shows a downward trend in sea ice across the Northern Hemisphere between 1980 and the 2000s. During some mild winters, many lakes that used to be dependably icy now remain slushy or fully liquid all winter. For the iceboating community, Thieler says, “climate change has been a real bastard.”

Over the two decades he’s been sailing, the season has shrunk. It used to be that the action revved up around Thanksgiving and sometimes lasted into the spring; he once sailed on Tax Day, in the middle of April. “In northern New Jersey, I know old guys who said they used to park boats on the ice in November and leave them until spring,” he says. “Now, it’s Christmas Day and it’s 60 degrees out and you take a walk on the beach.”

After a dicey incident years ago, when a boat broke through the ice, Thieler won’t sail on anything less than four inches thick. (“You learn not to push it,” he says. “I’ll be at the diner up the road, eating a hamburger.”) The trouble is that there are fewer and fewer days, and fewer and fewer places, that reach that threshold. He avoids places with spidery cracks and pooling water, as well as particularly shallow areas, the intersections of creeks, and places near piles of rocks, because those quick-moving or easily sun-warmed places can get surprisingly soft.

While it’s never impossible to find a place to sail (at least not yet), he adds, the ice isn’t as reliable as it used to be. “There are small lakes in Rhode Island that we used to sail all the time, and now we get on them once every other year,” he says. “It’s getting harder to find areas we can go.” Like other iceboaters, Thieler spends the week checking weather reports. Many clubs also have “ice lines,” or voicemail hotlines you can call to hear a member rattle off a list of places that might stay seized up and solid. (Anyone with a tip about sturdy stretches is encouraged to leave it after the beep.) “We as a community really rely on the folks who are checking and reporting ice conditions,” Morrone says. By tapping into this brain trust, Morrone has sailed seven days this season, and says that people who don’t work a typical Monday to Friday workweek are often able to sneak a few more outings in. Thieler tries to choose a location by Thursday. When the weekend arrives, he often finds himself in the car, heading north.

For Thieler and others, being an iceboater in a world with dwindling winter is a test of patience, which often wears thinner than the ice. Competitors who race DN ice yachts—a small class named after the Detroit News, which introduced the design in the 1930s—were disappointed when this year’s European championships, in Sweden, were called off earlier this month, after a flash of warm weather and a bit of rain softened the ice that had hosted the World Championships just the day before. Thieler, who raced in the Worlds, thought it was the right call. “I would rather go home with no races and no injuries than go home with a cast on and my boat in 100 pieces,” he says.

“It’s not too big of a stretch to make the case that 2020 will go down as another bust for most of the iceboating community,” writes John Sperr, a member of the Hudson River Ice Yacht Club, on his boating blog. In February 2020, many of the ice line messages were similarly melancholy, with just the tiniest shards of hope. “As we all know, it’s been a pretty dismal winter when it comes to iceboating,” muttered the voice on the line for the North Shrewsbury Ice Boat & Yacht Club, in New Jersey, in a message for the week of February 16, 2020. The less-gloomy news was that things looked a little more promising farther north, the speaker continued, in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, if some patchy areas would just melt a little and refreeze. (Quaboag Pond, which sits near Brookfield and East Brookfield, Massachusetts, was strong and slick, and a few iceboaters got some sailing in.) “Don’t give up yet,” the voice said. “We’re always a little optimistic around here. Let’s hope for the best.”

The sport is also dwindling because clubs are shrinking, Thieler says, and members tend to be older. “There’s an awful lot of gray hay and wrinkled skin in the fleet,” he says. “At 51, I’m sort of the new kid.” But there are still some new initiates, Morrone says, including college students. And there’s always a fresh crop of lifelong soft-water sailors who figure they’ll take the winter sport for a spin. Last weekend, in Kingston, Ontario, Thieler watched a soft-water sailor zip across the ice for the first time. “I gave him a push,” Thieler says, “and the last thing I heard as he was sailing away was ‘Yeehaw!’”

Even when the ice cooperates, there are “definitely some planets that have to line up to make a good sailing day,” Thieler says. Ideal sailing conditions also include a steady breeze blowing somewhere between eight and 15 knots, and smooth, black ice that’s not covered by wet or heavy snow, and has limited air bubbles. Thieler prefers temperatures between 25 and 35 degrees, because bitterly cold days court frostbite: “You can lose the end of your nose before you know it.” A windless afternoon isn’t necessarily a total wash: Mark Burns, the commodore of the West Michigan Ice Yacht Club, who has been boating for 25 years, switches to ice skates or skis when necessary, he says, to “try to make the best of it.” People do sail in less-than-ideal conditions, but there’s nothing quite like a perfect ice day, Thieler says. One of his friends, he says, compares it to choking down a flat beer, versus savoring a glass of champagne.

As those champagne days become rarer, they become more precious, too. Thieler and his girlfriend recently blew off some chores to drive to Canada to sail for the weekend. When climate change is coming for something you love, how can you not play hooky once in a while? There may be only so many chances left. It’s a carpe diem moment, with existential stakes. “Go do this while you can,” Thieler says. “In five or 10 years, we might not be doing this at all.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook