See 500 Years of Artful Nature Illustrations

Over 57 million pages of wildlife are catalogued.

The number of species on Earth is likely unknowable: There are simply too many hiding places for plants and critters, and the human gaze is too narrow and unfocused to look under every stone. Yet cataloguing the planet’s rich biodiversity has been a focus of the human mind for centuries. From Carl Linnaeus to John James Audubon, taxonomizing and documenting species have become lifelong pursuits. The unceasing desire to understand life more, and better, has kept the ball of discovery and categorization rolling for centuries.

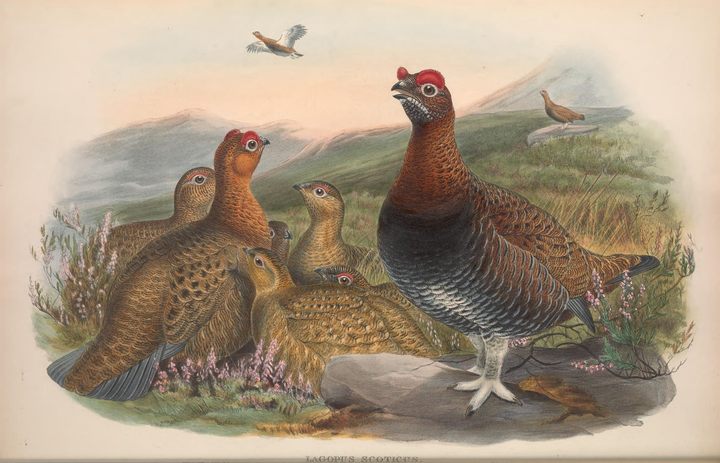

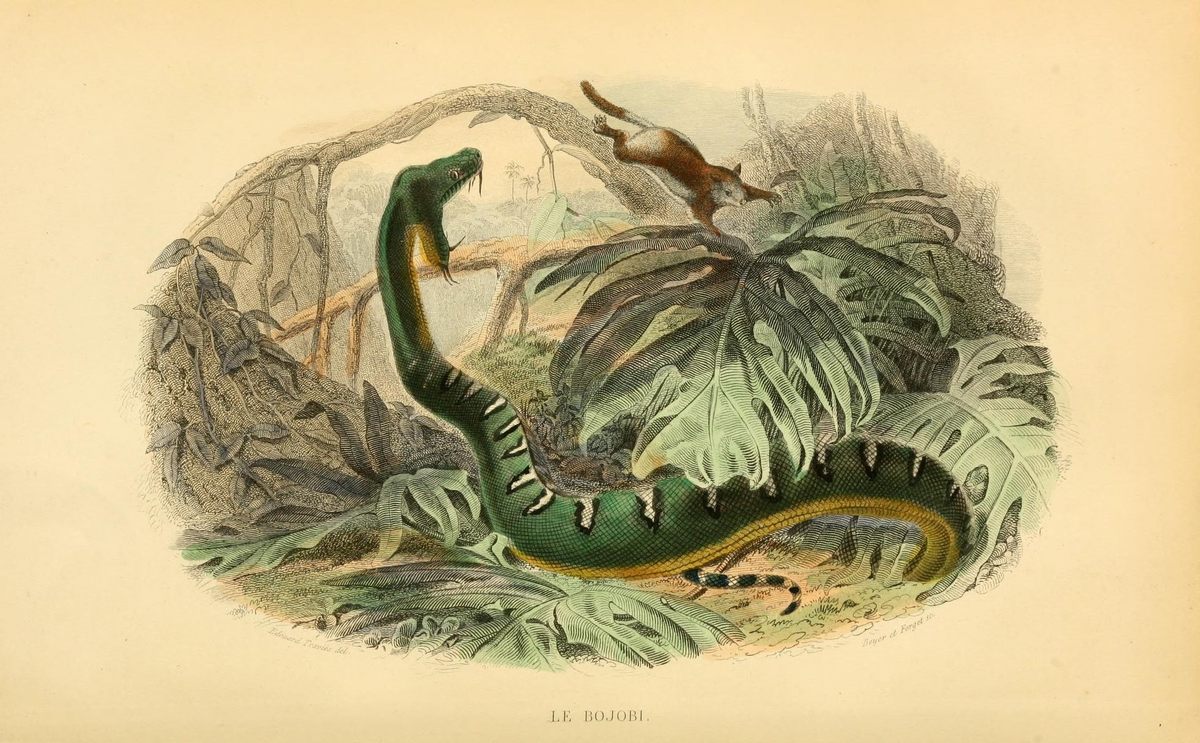

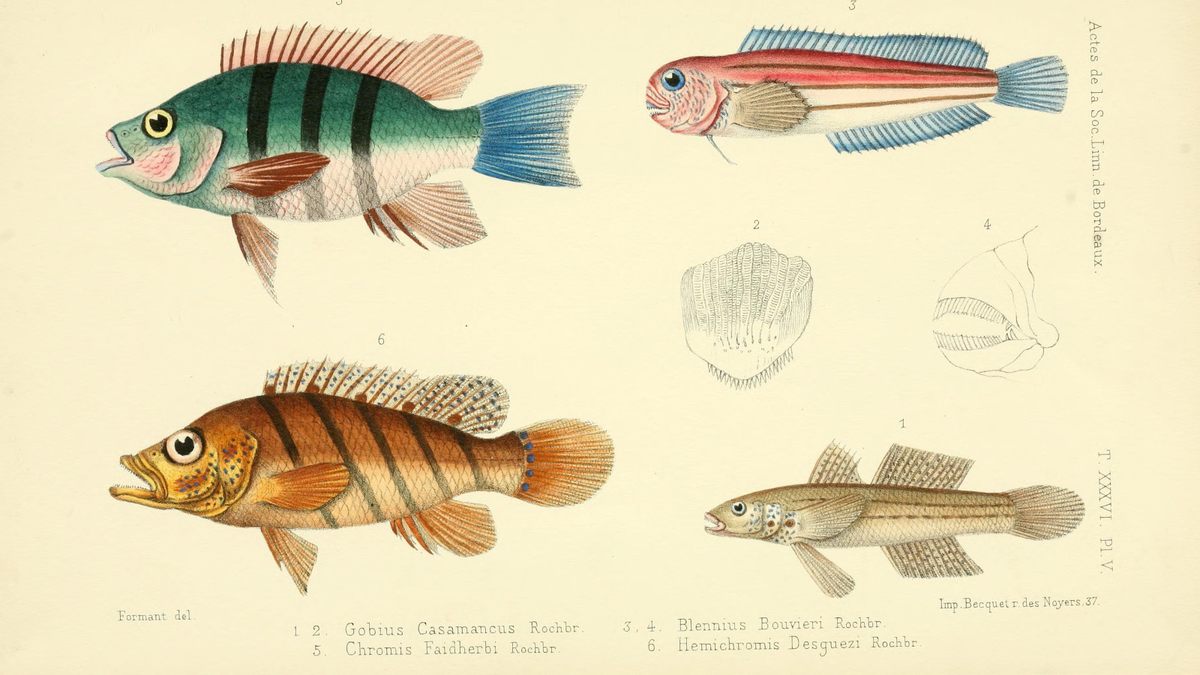

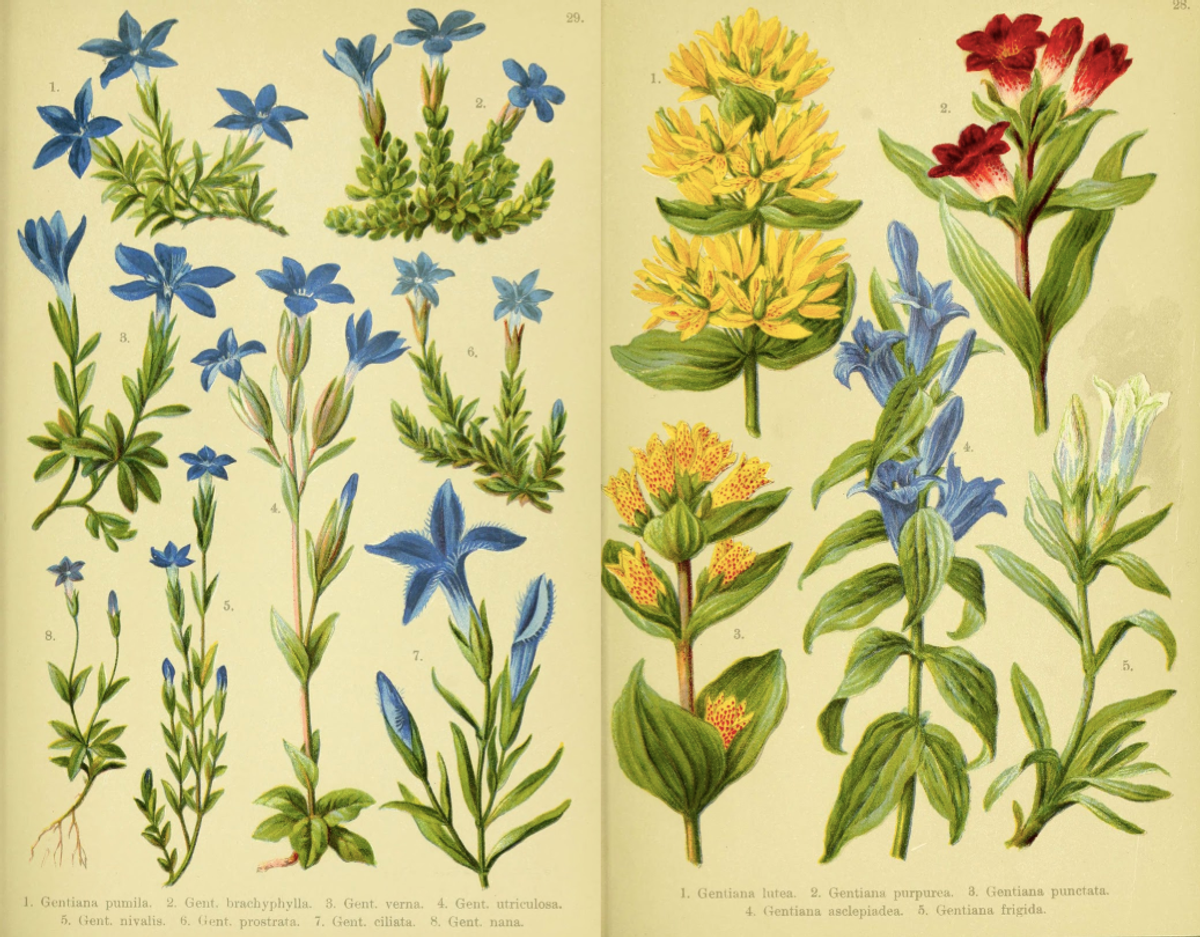

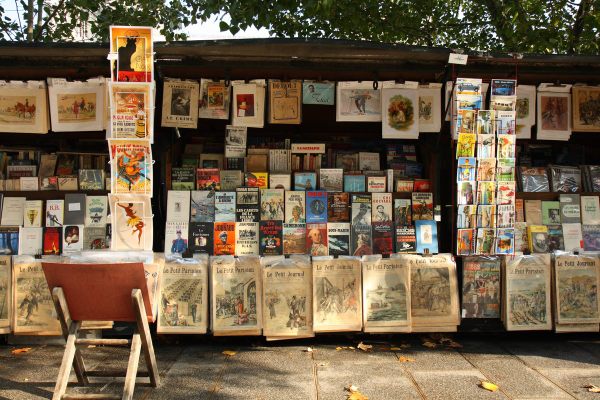

Now, the collaborative Biodiversity Heritage Library—a digital archive compiled by a consortium of natural-history libraries—has released over 150,000 artworks of the natural world, allowing public access to one of the largest illustrated compendiums of life on Earth. Years before wildlife photographers began to catalogue the world’s egrets, cephalopods, and rafflesia corpse flowers, artists like Elizabeth Gould were portraying species with illustrations, often reprinted as lithographs for the public. The online archive today boasts over 500 years of illustrated works, including some of Gould’s, totaling more than 57 million individual pages.

From the Bone Wars Collection, which describes a paleontological competition between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh, to the Early Women in Science catalogue, which elevates the work of scientists marginalized in their time, the library chronicles scientific events as they occurred and highlights previously understated histories and achievements.

The library is expanding at a time when much of life on Earth is under severe threat. Launched in 2006, the site states the importance of documenting species “in the midst of a major extinction crisis and widespread climate change.” It’s a grave mission, and the gravity has become only more obvious in recent years. Though we may not have the ability or will to save vanishing habitats and populations, we may at least have the bandwidth to memorialize them.

Given the age of some of these illustrations, not every one is scientifically accurate. But these images—of everything from barnacle-encrusted crustaceans to catalogues of Belgian horticulture—can still show us how animals and plants were seen in the mind’s eye of the naturalists of the time. They can also help us explore the remarkable march of evolution—and our understanding of it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook