The Hidden History of Shanghai’s Jewish Quarter

As Hitler rose to power, the city welcomed refugees.

It’s common knowledge that as Hitler’s bid to rid the world of Jews escalated, so did the world’s refusal to let them in. What’s not well known is that when those borders, ports, doors, windows, and boundaries began shutting Jews out, in part by refusing to issue them visas, Shanghai, though already swollen with people and poverty, was the only place on Earth willing to accept them with or without papers. It was an exception that, for thousands, meant the difference between life and death.

To understand the significance of this gesture, it’s important to understand the widely held but mistaken belief that Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe were never, at any point, permitted to leave. Henny Wenkart, a Holocaust survivor featured in the documentary, 50 Children: Mr. and Mrs. Kraus, explained this misconception: “What people don’t understand is that at the beginning, you could get out. Everybody could get out. Nobody would let us in!”

In fact, until 1941 when the routes immigrants used to get to Shanghai were closed off by the war and the Germans decreed that Jews could no longer emigrate from the Reich, Jews in occupied Europe were not only allowed to leave, but were pressured to do so through a system of intimidation and force. Although they didn’t make it easy, the Nazi party, eager to implement their plan to rid Europe of its Jewish population—to make it judenrein or “cleansed” of Jews—did allow Jews to leave under certain conditions.

“Potential refugees needed to get a variety of papers approved by governmental authorities, including the Gestapo, before they could leave,” writes Steve Hochstadt in an email. Hochstadt is Professor Emeritus of History at Illinois College and author of the book Exodus to Shanghai. “One document was the Unbedenklichkeitsbescheinigung, literally a ‘certificate of harmlessness,’ showing that there were no problems with this person, such as owing taxes. Jews needed to prove that they had registered their valuables with the authorities so they could be properly confiscated…”

Though difficult to obtain, those documents, along with proof of passage to another country and/or a visa for permission to enter another country, were enough to get one out of Europe. Surprisingly, even for those already detained in concentration camps, the door, metaphorically speaking, was open, provided they could prove they would leave Germany once released.

But of course, to walk through the door, one had to have some place to walk to, and that, for most Jews, was their biggest obstacle. Most countries made it either virtually impossible to enter (such as Switzerland, which insisted all German Jews have a red “J” stamped in their passports), imposed untenable conditions on refugees, or just simply wouldn’t issue visas.

Shanghai—already home to a few thousand Jewish immigrants who started slowly arriving as early as the mid-19th century for business or later to escape the Russian Revolution—not only did not require visas for entry, but issued them with alacrity to those seeking asylum. In many cases, newly arrived immigrants were not even asked to show passports. It was not until 1939 that restrictions were placed on Jewish immigrants coming into Shanghai and even then these limitations were decided not by the Chinese, but by the amalgam of foreign powers that controlled the city at the time. This body, made up both of Westerners and Japanese who wanted to restrict the influx of Jews, decided that anyone with a “J” on their passport would now have to apply in advance for landing permission.

A plaque at the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum in Hongkou explains the situation perfectly:

“No consulate or embassy in Vienna was prepared to grant us immigration visas until, by luck and perseverance I went to the Chinese consulate where, wonder of wonders, I was granted visas for me and my extended family. On the basis of these visas, we were able to obtain shipping accommodation on the Bianco Mano from an Italian Shipping Line [sic] expected to leave in early December 1938 from Genoa, Italy to Shanghai, China – a journey of approximately 30 days.”—Eric Goldstaub, Jewish refugee to Shanghai

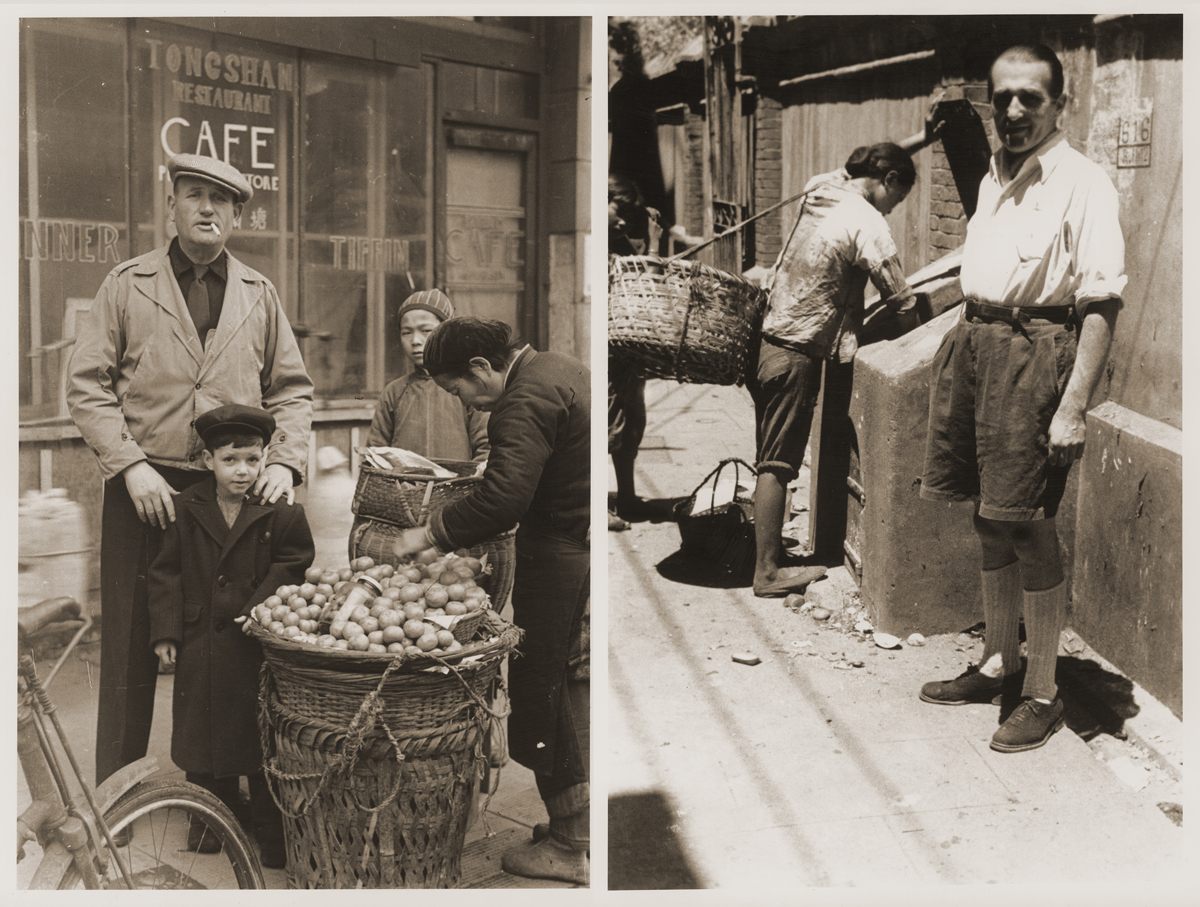

And so, without the luxury of options, and desperate to evade the tightening grip of the Nazis, Jewish refugees by the thousands, as well as a small minority of non-Jews, set sail from Germany and parts of Central and Eastern Europe, settling primarily in the Hongkou neighborhood of Shanghai. Having been stripped of most of their assets upon their departure from Europe, the virtually penniless arrivals found Hongkou much more affordable than the city’s more developed districts.

Although they came in a slow but steady stream from the beginning of Hitler’s rise, it was Kristallnacht in 1938 that catapulted the Jewish population in Shanghai from a few thousand to upwards of 20,000. Over the course of two days, Jewish businesses in Germany, annexed Austria, and what was then known as the Sudetenland (a region in what was then Czechoslovakia with a large German population) were looted, Jewish homes were destroyed, and Jewish men were arrested and taken to concentration camps. The migration that arose out of this traumatic event “ … lasted only until August 1939, when all the foreign powers in Shanghai decided to implement restrictions, which severely cut down the number who could enter,” writes Hochstadt.

The Shanghai of the early 20th century was in many ways an energetic, challenging city that attracted the driven and ambitious. Shopping, theater, education, music, publishing, architecture, and even film production flourished, but as Harriet Sargeant, author of the book Shanghai explains, the assault on the city by the Japanese proved too much: “Between 1937 and 1941 the Japanese oversaw the destruction of Shanghai. One by one they stripped away the attributes which had made it great. When they finally seized Shanghai itself in 1941, they found the longed-for city no longer existed. The Shanghai of the ‘twenties and ‘thirties had gone forever.

Troubled from the crushing Second Sino-Japanese War, Shanghai was a raw place. The refugee Ursula Bacon in her book, Shanghai Diary: A Young Girl’s Journey from Hitler’s Hate to War-Torn China, describes the scene she discovered upon arrival in Shanghai: “Boiling under the hot sun and steamed by the humidity in the air was the combination of rotting fruit peelings, spoiled leftovers, raw bones, dead cats, drowned puppies, carcasses of rats, and the lifeless body of a newborn baby …”

Nevertheless, many of the Shanghai locals, in spite of their own hardships, welcomed their new neighbors and shared what little they had, whether that meant housing, medical care, or just simple kindness. Gradually, with that support, Jewish refugees began, little by little, to create lives in their new country, and before long, the proliferation of Jewish-owned businesses was such that the Hongkou area became known as “Little Vienna.” Like their Chinese neighbors, they did their best to survive in difficult circumstances. They established newspapers, synagogues, retail businesses, restaurants, schools, cemeteries, guilds, social clubs, and even beauty pageants. They practiced medicine, started hospitals, got married, had babies, and held bar and bat mitzvahs. They learned to cook in coal-burning ovens and to haggle with street vendors.

One Hongkou resident remembers the time and place with great fondness. The artist Peter Max, who would later become known for his signature “psychedelic” works of art, came to Shanghai with his parents after fleeing Berlin. Like many of the Jewish families who immigrated to the city, Max’s father started a business, in this case, a store that sold Western-style suits. It was, Max recalls, an auspicious choice, as Chinese men were just beginning to favor them over their traditional Mandarin clothing.

“On the ground floor of our building was a Viennese garden-café,” Max recalls, “where my father and mother met their friends in the early evenings for coffee and pastries while listening to a violinist play romantic songs from the land they had left behind. The community of Europeans that gathered and grew below our house kept me connected to our roots.”

The people of that community lived their lives as normally as possible until 1942, when the history they came so far to escape came dangerously close to repeating itself. Shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Colonel Josef Meisinger, Chief Representative of Nazi Germany Gestapo to Japan, approached the Japanese authorities in Shanghai with “The Meisinger Plan,” a scheme to rid the city of its Jewish population by starvation, overwork, or medical experiments. Although the Japanese ultimately rejected that plan, starting in February 1943, they did require that every Jewish person who came to Shanghai after 1937 relocate to Hongkou, a relatively small area that already had an existing population in the hundreds of thousands.

Although much of the city’s Jewish population was already living there, the crush of one population on another also dealt a brutal blow, with both disease and lack of food becoming even more critical concerns. Suddenly, curfews were imposed. Passes to exit and enter the ghetto were required. Food rations were implemented. It was not uncommon for 30 to 40 people to sleep in the same room (reports of up to 200 people in one room exist) and “bathroom” facilities in general consisted of little else than literal pots emptied by local laborers each morning. Still, refugees bolstered themselves by remembering that, in spite of these conditions, in Shanghai, they were the one thing they could not be in Europe: safe.

Between the dismal state of the still-impoverished city and the beginning of the Chinese Communist Revolution in 1949, the city’s post-war Jewish population eventually dwindled to just a few hundred people, although there are said to be a few thousand Jews living there today. Eager to return to Europe or start new lives on other continents, most Jewish refugees left Shanghai at the end of WWII and with their departure began the dismantling of the culture and lives they established in China.

Although the nearby apartment buildings that once housed both European Jews and Chinese alike are still in use, given Shanghai’s current construction boom, it’s not unthinkable that these monuments, too, could soon meet the wrecking ball. The White Horse Inn, a Hongkou café opened by Viennese refugees in 1939 that became not just a meeting place but something of a symbol of normalcy for the displaced Europeans, was demolished almost ten years ago for a road widening project. Other businesses of the era, once so crucial to the Jewish experience in Shanghai, are now represented only by rescued signage that hangs in the courtyard of the neighborhood’s Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum.

The museum, which includes the Ohel Moishe Synagogue, a center of Jewish life and worship for the Hongkou refugees, has become something of a touchstone of this extraordinary circumstance of history but between the exodus of the original Jewish population after the war and the city’s lack of interest in preserving this chapter of its past, one has to wonder if it will soon be the last monument to it standing.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook