The Great Sandwina, Circus Strongwoman and Restaurateur

Katie Brumbach enjoyed hoisting her husband above her head and making diners feel at home.

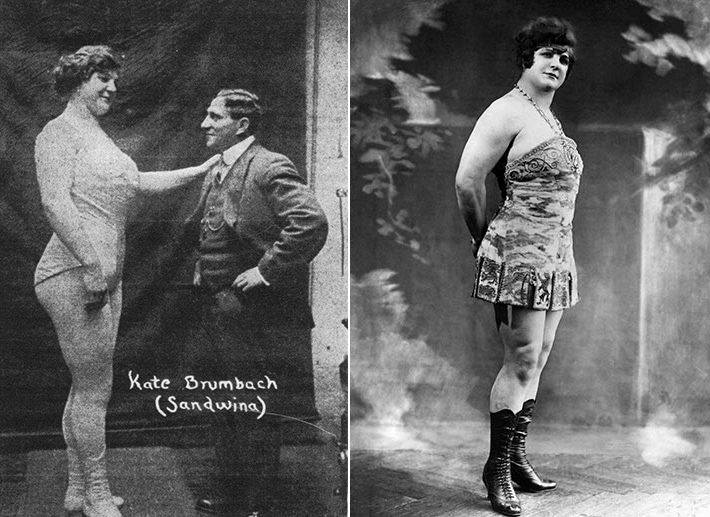

As one of at least 14 children born to a pair of Bavarian circus performers, Katie Brumbach began her career as a renowned strongwoman at the ripe old age of two. Better known as Lady Hercules or The Great Sandwina, Brumbach was born in the back of a circus wagon outside of Vienna, Austria, in 1884. She was practicing handstands on her father’s palms when many children were still learning to walk, and she had established herself as an integral part of the family’s circus act long before entering her teens.

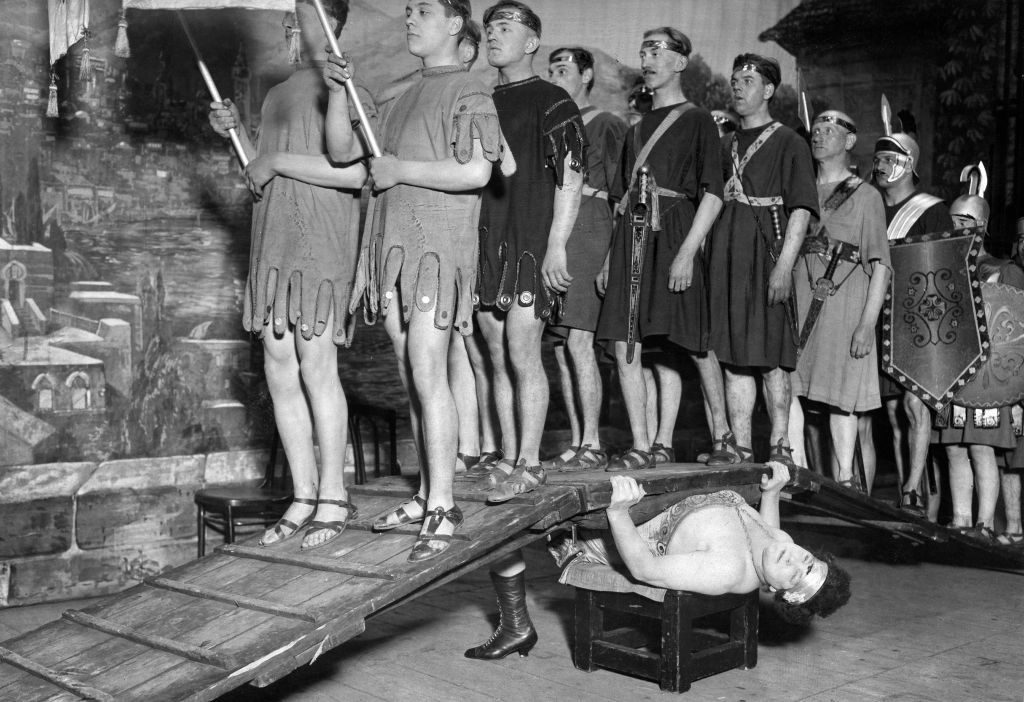

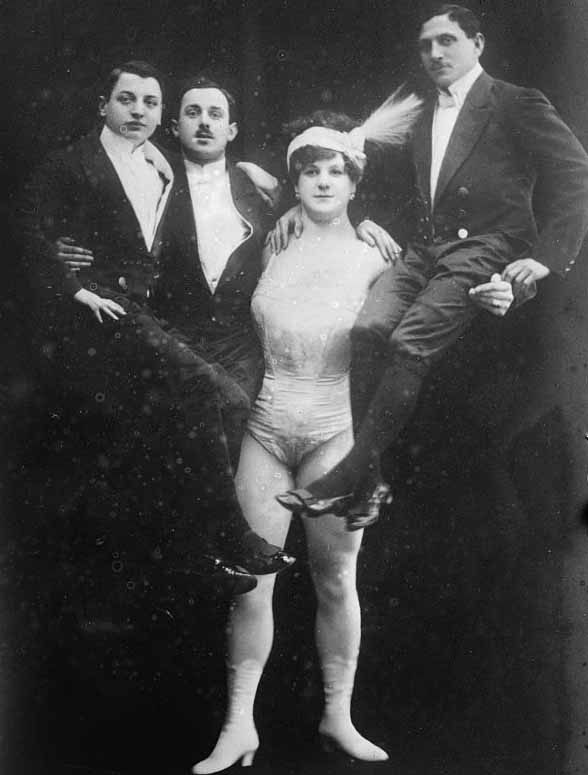

In addition to performing astonishing feats of strength, Brumbach was an accomplished wrestler, and her early acts with the family circus included a segment where her father, the 6’6” strongman Phillipe Brumbach, offered a prize of 100 gold marks to any man who could beat her in the ring. Brumbach was never defeated, but when she was 16, an aspiring acrobat named Max Heymann thought that trouncing a woman on stage might be a good way to garner publicity for his career while also making some quick cash. Brumbach soundly defeated the petite Heymann, but as he looked up from his vantage point from the ground on which she had thrown him, he fell in love; the two were married for 52 years. Brumbach quickly incorporated her 5’6” husband into her act, hoisting him over her head with one hand and performing a routine where she “played the role of a soldier going through a rifle drill, manipulating Heymann as if he were a rifle.”

Brumbach and her husband branched off from the family circus and came to the United States in the early 1900s, and while in New York in 1902, Brumbach crossed paths with Eugene Sandow, the leading strongman of the era. The two champions faced each other in a public weightlifting showdown, hefting progressively heavier weights until Brumbach bested Sandow by raising 300 pounds above her head with one hand; Sandow only managed to raise the weight to his chest. In an act that was perhaps equal parts homage and emasculation, Brumbach changed her last name to Sandwina, a female derivative of Sandow, to mark her victory, and began performing as The Great Sandwina.

As her career progressed, Brumbach introduced increasing levels of theatricality to her act. A 1927 article from the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette described how she

thinks nothing of snapping with her fingers an iron chain of which each link is guaranteed to stand a 4,000 lb strain, and to bend formidable iron bars into fantastic shapes. More striking achievements comprise the balancing on her chest of a revolving merry-go-round with half-a-dozen adults; throwing from her body half a ton of stone which had been placed on it, with great difficulty, by eight men; while she concludes the turn by serving as the foundation of a bridge, over which pass, in double file, a number of people, followed by a full-grown cart horse!

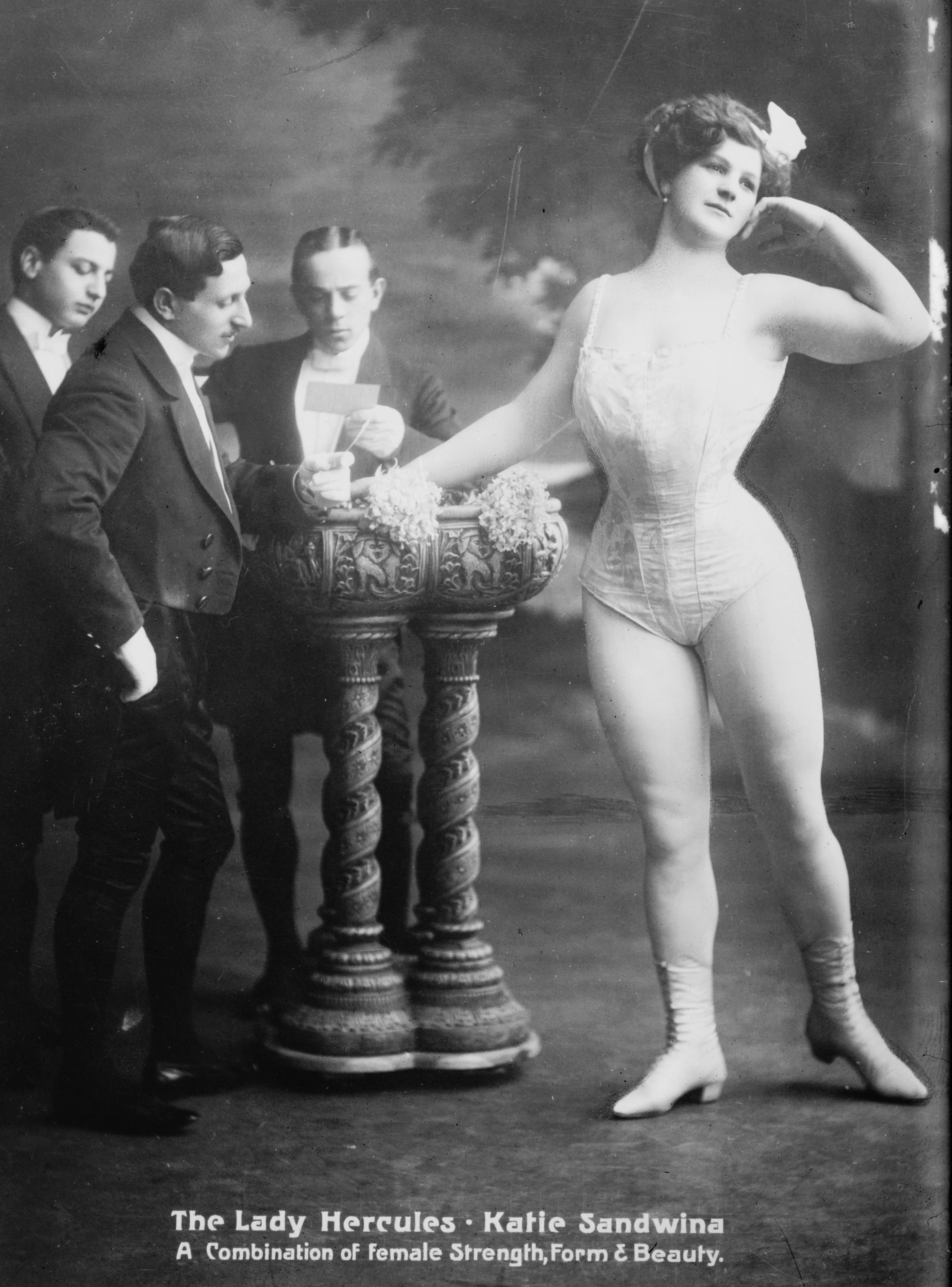

Brumbach embraced her strength while maintaining her personal sense of femininity, and saw no contradiction between her love of painting her nails and her ability to deflect sledgehammer blows to the chest. Unlike other strongwomen of her era, she was never described in masculine terms, and the press paid as much attention to her hourglass figure as her prowess at casually bending horseshoes. A 1911 article in The New York American tells how “the beauty of her features [is] positively startling. With her curled upper lip and her classic chin, she has the look of some heroic work in marble … Her throat is a column. Her shoulders and back might have been hewn by Michel Angelo [sic].”

When Brumbach was signed to the Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1911, she was the star of a meet-the-press event* at Madison Square Garden, in which 10 physicians from all over the country were shipped in to publicly examine Brumbach’s physique. After declaring her stats—she “stood 5 feet 9 ¾ inches tall, weighed 210 pounds, and had a 44 1/10 inch chest measurement when expanded, a 29 inch waist, 43 inch hips, a 16 1/10 inch calf, and her flexed right biceps measured 14 inches”—the examining physicians concluded that “In every way, according to her measurements, she is a perfect woman by all the accepted standards.”

Brumbach defied gender conventions of her era in other ways by speaking candidly about her sexual appetites, and in an interview in the German newspaper Woven Man Spricht, she spoke openly about her enjoyment of men:

“A very discreet question, my dear madam! Are you married?”

“No, I’m not married. I’m still single but nobody dares to end this situation.”

“Are you interested in men, anyway?”

“What shall I say? Men are like air to me, you can’t live without them. Every now and then I breathe good fresh air, you know.”

Later, Brumbach became a mother (and, of course, performed up until the night before her first son was born) and seamlessly fused her identities as a strongwoman and a matriarch by introducing her sons—Theodore, who was born in 1909 and would go on to become a successful heavyweight boxer, and Alfred, an actor born in 1918—into her act.

Her championship of female strength was not confined to her own life circumstances, and Brumbach was an outspoken proponent of the women’s right to vote. In 1912, she became the vice-president of the 800-member Suffragette Ladies of the Barnum & Bailey Circus, and was sometimes referred to as Sandwina the Suffragette. According to a 1910 Barnum & Bailey promotional article titled Happy Family Ruled by Giantess Makes Anti-Suffragists Tremble, “The anti-suffragists who go to the Barnum & Bailey Circus at Madison Square Garden, and see Sandwina, the German strong woman, lift her husband and two-year-old son with one arm, tremble for the future of the anticause. When all women are able to rule their homes by such simple and primitive methods they will get the vote—or take it.”

Brumbach continued to perform with Barnum & Bailey for decades and was nearly 60 when she finally retired. She lived seven more years, dying of cancer in 1952. In her later years, Brumbach and Heymann opened a cafe in Ridgewood, New York just on the border between Queens and Brooklyn. Large billboards mounted outside the business declared the owner as The Strongest Woman in the World, but like her circus act, the restaurant was a family affair: with her husband cooking and her son bartending, Brumbach was free to serve as the amiable host—but upon request, she would happily bend iron bars and break heavy chains to entertain cafe patrons.

After so many years in the spotlight, Brumbach was content to settle into a quieter second act, but from time to time, her strongwoman past would resurface with aplomb. “One afternoon,” recounted a 1947 article from the New York Mirror, “a bruiser walked in and after berating everyone in sight, started for Papa.” Brumbach “floored the bruiser with one punch for the whole count and gave him a thorough lesson as she tossed him out.”

*Correction: The story originally said that P.T. Barnum was personally involved in the 1911 meet-the-press event. Barnum died in 1891. He was not, therefore, present.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook