The Voluminous Shell Heaps Hidden in Plain Sight All Over NYC

Oyster middens were everywhere for thousands of years, until suddenly they weren’t.

A 1935 photograph by Berenice Abbott of oyster houses on South Street and Pike Slip, Manhattan. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

Hundreds of feet long, buried in the earth, thousands of oyster shells are pressed against one another, overtaking the few shards of bones and broken pottery within its depths. The monstrous heap is heavy and enormous—and it’s literally a pile of garbage. If you’re in one of the coastal areas of the world, particularly in New York, that oyster garbage might even be beneath your feet right now.

These huge, ancient heaps of shells are called oyster middens, and they’ve fascinated people for centuries. If you didn’t know better, the word “midden” might sound homey and adorable, like a lush green burrow for some fuzzy, ground-dwelling animal, but you’d be mistaken. A midden is an archaeological term for a pile of trash left by humans long gone, and oyster middens are some of the oldest and largest piles of intact garbage dating from after the late ice age.

Sometimes buried in layers of dirt and sand, sometimes piled high, the densely packed shells turn up anywhere oysters were consumed as a source of food. Hundreds existed along coasts all over the world, including Australia, Argentina, Denmark, and the U.S.—but common as they were, few exist today, begging the question: where did all of the oyster middens go?

Oysters photographed in 1908 for New York Fish and Game Commission. (Photo: Freshwater and Marine Image Bank/Public Domain)

New York journalist Daniel Tredwell wrote in 1839 that the middens were plentiful, and “bleached white as snow,” a beautiful memory from his childhood. These piles were a legacy from when the Hudson was once a rich oyster bed, full of succulent bivalves for the ancient peoples of the New York and New Jersey coasts. The Lenape of Manhattan ate oysters regularly, as did their ancestors, chucking the shells into enormous piles over thousands of years. The middens helped inform the names of early New York streets; the intersection of Canal Street and Bowery was once called “Shell Point” in Dutch. Pearl Street in Manhattan was named after a midden, and later paved with oyster shells.

There were once so many oyster middens in New York that much of the city’s infrastructure is literally built on top of them. In The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell, Mark Kurlansky writes that “numerous known sites lie beneath railroad tracks, city streets, dreaded landfill, highways that hug the coastlines, and docks,” and that near what was once called Collect Pond, a midden is buried beneath the federal and state courthouses “and the shops and restaurants of Chinatown.”

Not all middens are hidden in plain sight beneath buildings, roads and railroad tracks. Some middens still tower above the ground, and can be massive. A midden at Florida’s Timucuan Ecological & Historic Preserve spreads across more than 25 acres, thick with 25 feet of oyster shells dating from 600 to 2,500 years ago; some of the oldest pottery in North America was found in these mounds, according to the St. Johns River History Society. In Dauphine, Alabama, one midden is 164 feet across and 22 feet high, created between 1110 and 1550.

A stereoscopic view of oyster banks on the Damariscotta River, Maine. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

The Glidden Midden of Maine, near the Damariscotta River, is the largest in the northeastern states, but it doesn’t compare to the size that its neighbor, the Whaleback Midden, once was: 1,650 feet in length, and over 1,320 feet wide—it was, like many of the middens, taken apart bit by bit in the 1800s to fortify the foundation of roads, make mortar, and supplement chicken feed. “The size of it has depreciated considerably since the time it was created,” says Sarah Gladu, the Education Director at the Damariscotta River Association in Maine, which co-maintains Whaleback Shell Midden State Historic Site, and just a fraction of the midden remains today.

Indeed, after surviving for thousands of years, most middens did not escape the last three centuries unscathed. European colonizers thought of the shell heaps as an obvious available resource for the taking; shells were easily dried and burned into a quick lyme paste, making a sturdy cement for buildings used in the 1600s, and the calcium-rich shells were good for farming and reading soil for crops. Unfortunately, in 1886, the Damariscotta Shell and Fertilizer company got their hands on the Whaleback Midden, and whittled it down to make ground-down calcium supplements for chicken feed until almost nothing was left just five years later.

This is typical of the oyster middens; throughout the colonial era and through the 1800s, this sort of damage to the shell heaps increased. Ancient shells were briskly shoveled as filler in place of rocks to build foundations for new railway and road systems; the Hudson Railroad and Metro North lines of New York ran over and through dozens of middens.

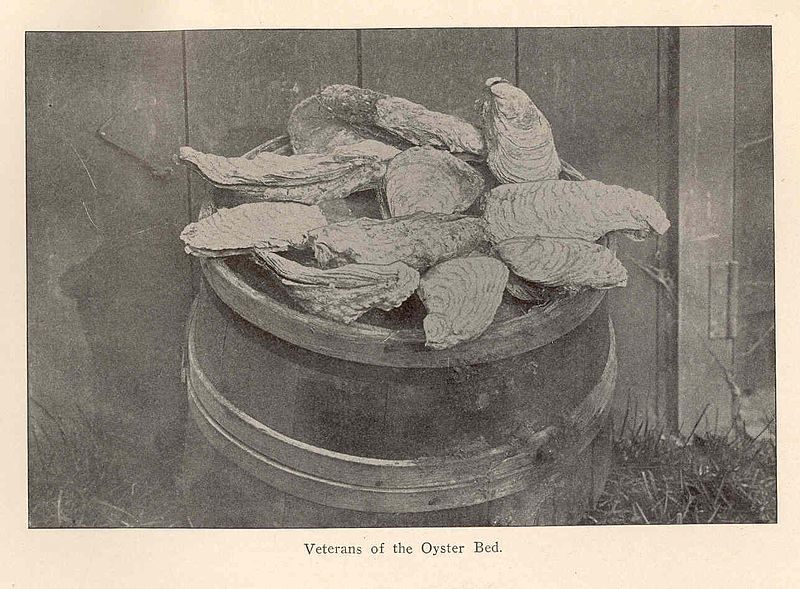

Oyster market in Manhattan, c. 1903. (Photo: Freshwater and Marine Image Bank/Public Domain)

In 1894, the Office of Public Roads held a meeting to gather suggestions for road building methods, with representatives from different states. At the meeting the Florida Railroad company noted the “large mounds of snail and oyster shells on the coasts,” which “contain enough lime to thoroughly cement the shells and soon become equal to well made concrete.” During the meeting, a Mr. Stevenson, representing North Carolina’s interests, reportedly said that an oyster road he knew of “costs very little to keep up, yet it is always in repair,” and “a thing of beauty and joy forever.”

These days, it’s illegal to disturb an oyster midden without express permission, making them some of the most valuable and well-respected trash piles around. When archaeologists excavate a midden today, they painstakingly document every object and its relation to other objects found with; context is key—when that, or the midden itself is gone, it can’t be replaced.

The Whaleback and Gladden Middens are somewhat unique as middens go; while archaeologists have found evidence of dumping, including a dog skeleton, and the skeleton of the now-extinct bird, the great auk, Whaleback Midden had very few signs of garbage other than shells. “Many middens had old tools and bones—it’s really just a rubbish heap that people have assembled over thousands of years… but the Whaleback and Glidden Midden is actually fairly refuse-free,” says Gladu. “There has been some speculation between archaeologists that maybe this midden is not just a garbage heap, and might have some spiritual significance on some level.”

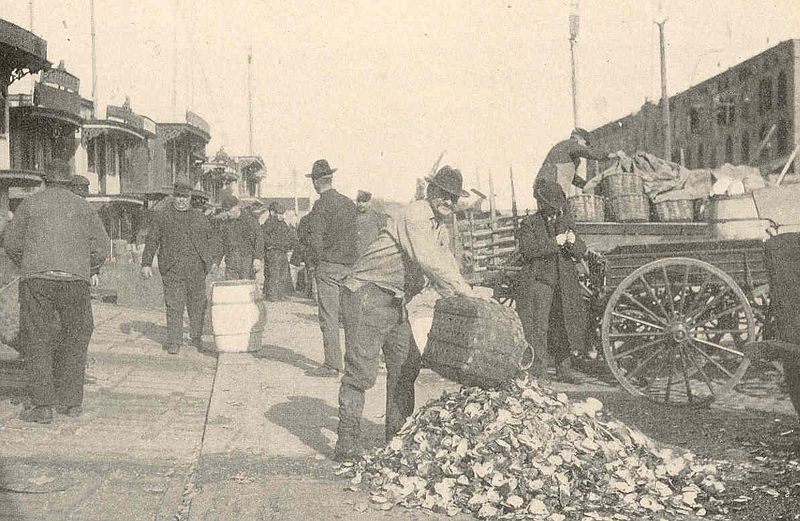

The oyster market at Perry Street, 1893. (Photo: British Library/Public Domain)

Oyster middens still pop up every now and again, often rediscovered by accident. During a 1980s restoration of the Statue of Liberty, an oyster midden was found on Liberty Island, and yielded over 9,000 artifacts–ancient tools, bones, broken pottery, and refuse from countless past dinners–before the excavation wrapped up in 1998. In the late 1980s, a planned condominium development in Dobb’s Ferry, New York, was halted so that archeologists could excavate its local midden, which dates back to 6950 B.C.E. and is the oldest evidence of human life in the area. To put its age into perspective, around the estimated time that Stonehenge was being built, the early inhabitants of New York were enjoying an oyster party.

While the plentiful, snow-white oyster middens once so visible on coasts have largely disappeared from the landscape, or been buried by it, one wonders what our own middens might tell future archaeologists. Will they take an interest in our snow-white deposits of styrofoam takeout boxes, noting the frying grease on chicken bones? It’s highly possible. Whatever comes of our own garbage, we can take comfort that the dinner party scraps of the ancients exist all around us, snugly tucked away in places we’d never expect.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook