Thomas Jefferson’s Dream to Rid the Oceans of Salt

A massive new industry in modern times, desalination has a long history.

The Port Stanvac desalination plant in South Australia. (Photo: Vmenkov/CC BY-SA 3.0)

A version of this post originally appeared on the Tedium newsletter.

Salt is a great substance, and one that deserves an important place in our culture.

But salt also renders nearly all of our water supply undrinkable.

As drought has increasingly become a problem globally, however, scores of countries are turning to a solution with a long, expensive, and controversial history: desalination, or the process by which salt and other minerals are removed from seawater.

Around the world, the number of people suffering from water scarcity is expected to more than double in less than a decade, to around 1.8 billion. Demand for desalination, as a result, will only grow. But some have questioned the environmental costs of desalination plants, and wondered whether our planet’s neverending thirst for more water is beginning to do more harm than good.

The desire to make water from the oceans potable is far from new, however. Just ask Thomas Jefferson.

In 1790, when Jefferson was Secretary of State, he made a trip to Newport, Rhode Island, where he was given a bottle by a guy named Jacob Isaacks. In the bottle, Isaacks claimed, was “purified” salt water.

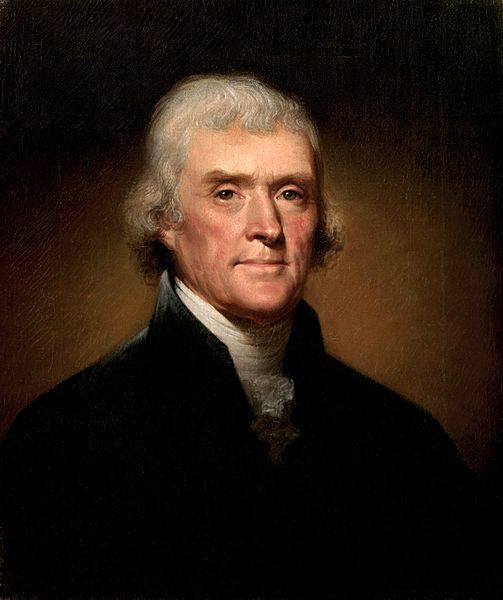

Thomas Jefferson’s 1800 portrait by Rembrandt Peale. (Photo: Public Domain)

Isaacks, then 71, said his proprietary mixture could be added to salt water; the mixture would then filter it just enough to drink. Jefferson, tasked with researching things that would be beneficial to the fledgling U.S. military, took Isaacks’ idea seriously, going so far as to create a team of people—including two chemistry professors—to see if they could confirm that Isaacks’ idea worked.

At the very least, the group found, Isaacks’ water tasted slightly better than its untreated equivalent.

“The distilled water in all these instances was found on experiment to be as pure as the best pump water of the city: it’s taste indeed was not as agreeable; but it was not such as to produce any disgust,” Jefferson recalled in a 1791 report on Isaacks’ creation. “In fact we drink in common life in many places and under many circumstances and almost always at sea a worse tasted, and probably a less wholesome water.”

Ultimately, however, Jefferson and his fellow experimenters could not prove that Isaacks’ method of production actually removed the salt. “Mr. Isaack’s mixture does not facilitate the separation of seawater from its salt,” Jefferson stated in an affidavit immediately after the experiment.

A reverse-osmosis desalination plant in Barcelona, Spain. (Photo: James Grellier/CC BY-SA 3.0)

And soon enough, Isaacks realized that working with Jefferson on his bajillion-dollar idea was a dead end, and he began researching other options for his technology, which he hoped to sell. But a report Jefferson later gave Congress all but killed Isaacks’ business prospects. That report highlighted the fact, contradictory to what he had been claiming, that Isaacks didn’t actually invent desalination. (Hours after sending the report to Congress, Jefferson received a letter from Isaacks asking him to delay the release.)

Later, Jefferson wrote Isaacks to explain.

“That the discovery was original as to yourself I can readily believe,” Jefferson wrote in a letter to Isaacks. “Still it is not the less true, that the distillation of fresh from seawater, both with and without mixtures, had been long ago tried, and that without a mixture, it produced as much and as good water as in your method with a mixture.”

Isaacks’ angry response to that letter didn’t do much for him or his method; both have become historical footnotes.

Drought in Queensland, in Australia. (Photo: Beau Giles/CC BY 2.0)

These days, desalination is common place, both something you can do in your backyard and an ever-growing mass industrial complex.

In California, for example, the Claude “Bud” Lewis Carlsbad Desalination Plant went online in December, capable of producing up to 54 million gallons of fresh water per day.

It didn’t happen overnight. The plant has been in the works for nearly two decades at a cost of $1 billion, now producing one cup of fresh water for every two cups of salt water. But even with the plant’s massive output, it produces just 10 percent of the water needed daily in San Diego County.

A desalination pipeline in Nuweiba, Egypt. (Photo: Silke Baron/CC BY 2.0)

In addition to the expense and inefficiency of plants like the one in California are the environmental costs. Many produce greenhouse gases, and the process can also destabilize local ecosystems and even hurt wider biodiversity throughout the ocean.

“Seawater desalination can cause impingement and entrainment of marine organisms and create ecological impacts from concentrate discharge,” according to a 2008 report issued by the National Research Council. “Desalination of inland brackish groundwater sources could lead to groundwater mining and subsidence, and improper concentrate management practices can negatively affect drinking water aquifers and freshwater biota.”

These concerns are partially why plants like the one in Carlsbad, and a similar plant being discussed in nearby Huntington Beach, are frequently the subject of controversy. And it doesn’t help that these plants spit extra-briney water back into the ocean.

California is far from alone in facing this dilemma. According to an industry organization, 150 countries employ desalination worldwide, and there are over 18,000 plants currently operating, producing nearly 23 billion gallons of water daily.

As water scarcity increases, in part because of climate change, those numbers will only go up. In many places like the Middle East, which relies on desalination far more than other parts of the world, there may not be much of a choice.

But one alternative, of course, isn’t much of an alternative at all: Drinking untreated seawater is a very quick way to die by dehydration, as seawater has more salt on average than exists in the human bloodstream. It may be different for the rest of the animal kingdom, but, for humans at least, our quest for potable water may be the ultimate case of supply outpacing demand.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook