The Tale of the Toad and the Bearded Female Saint

European women used to leave toad votives in holy places as pleas for divine help.

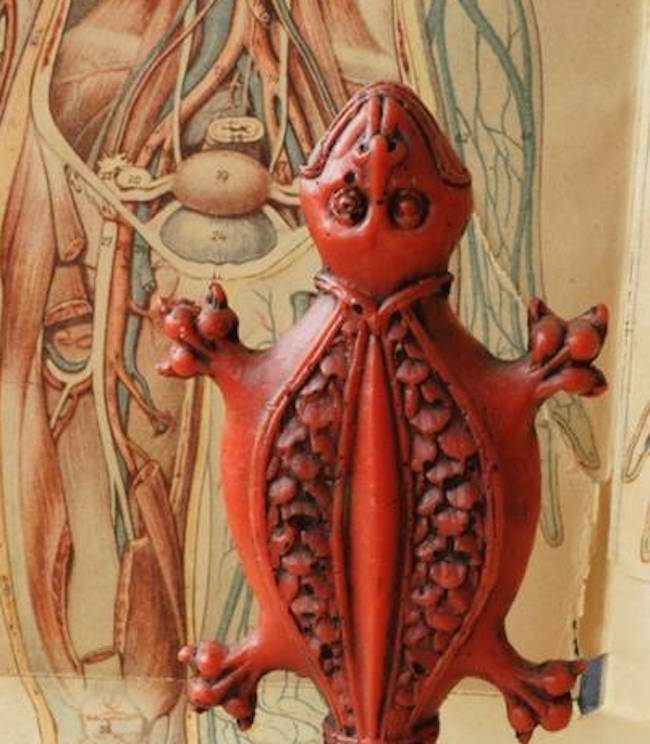

Of all the regions where little toad sculptures were placed as offerings at Christian holy sites, southern Germany was the most enduring—extending from the medieval period through to the 19th century. But at one time, women in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Italy all brought small toad votives, made of wax, wood, or metal, to the shrines of certain saints to request holy intercession in matters of childbirth.

There’s a certain logic to the offering, as in the medieval mind, toads were sometimes considered vaginal symbols. But the amphibians could take on many roles. “Apparitions of toads can have all different modalities and meanings,” writes Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, a University of Pittsburgh professor who specializes in medieval literature, in her book The Strange Case of Ermine de Reims, about a woman haunted by visions of toads and other creatures. In addition to their association with childbirth, toads (like vaginas) were also linked to sin, magic, and evil. Perhaps it’s appropriate that one of the figures most closely associated with toad votives is a gender-bending saint who has never been officially recognized by the church.

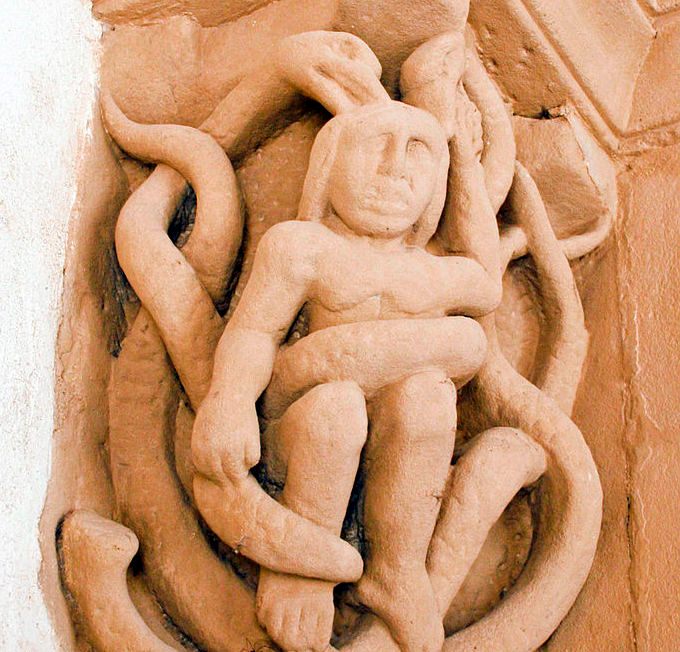

In the medieval world, toads were charter members of the cabal of slimy, devilish creatures imbued with powers and beloved of witches—tormentors of the sinful mind. In one medieval church sculpture motif, the femme aux serpents, the embodiment of sinful lust, toads sometimes sub in for the snakes that writhe around a woman’s body and occasionally bite her breasts. But toads weren’t as purely evil as snakes; they could be humorous, too. In one German story, a woman loses her vagina and it “is mistaken for a toad as it roams the streets,” writes Blumenfeld-Kosinski. (Eventually, the woman gets her detachable vagina back.) Toads were also thought to have the power of spontaneous generation and resurrection.

From this amalgam of symbolism emerged a connection with the womb, so women brought votive statues shaped like toads to ask religious figures to intercede in feminine problems. One might be left after praying for relief from a gynecological problem or the pain of childbirth, or after women prayed to become pregnant or expressed concerned about the health of their unborn children. In southern Germany, where the practice persisted, the figures were made from red wax, which was thought to offer protection from the devil.

In the medieval period, toad votives were closely associated with particular saints. In one variation, toads offered to St. Roch were “metal toads with baby faces and large, vulvalike openings on their backs believed to be substitutes for representations of uterus,” writes Blumenfeld-Kosinski in Not of Woman Born. More often, though, they were found with images of St. Wilgefortis, also known as “Kümmernis” or “Uncumber,” whom one scholar describes as “one of the most interesting of all the ecclesiastical conceptions” and another as “possibly the most spectacular of the grotesque saints and certainly one of the most important.”

St. Wilgefortis had no chapels dedicated specifically to her, but according to David Williams, author of Deformed Discourse, her cult thrived in the 15th century, and those chapels where her image was found sometimes had mysterious underground passages associated with them. She was the patron saint of monsters and people who suffered from deformities, and also of crops, travelers, and the marital bed.

Wilgefortis’s story, which is not believed to have any basis in fact, is that she was one of seven daughters of a Portuguese pagan king. She found Christianity and vowed to stay a virgin, but her father went against her wishes and pledged her hand to the King of Sicily. After she prayed to be spared from this fate, she grew a beard. It saved her from marriage—but not martyrdom. As late as the 19th century, women prayed to Wilgefortis for children and “as a source of fertility,” writes Williams. “As a sign of this, votives in the form of a toad were hung under her image.”

The toad was, for medieval women, a source of agency, of private power that they were willing to use in times of need—even if it was never officially sanctioned by the church that governed their daily lives.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook