Truman, Trump, and Why Presidential Candidates Get Top Secret Intelligence Briefings

A brief history.

They were originally Harry Truman’s idea. Here’s Truman with Josef Stalin, left, and Winston Churchill in July 1945. (Photo: Unknown/CC BY-SA 3.0)

For weeks, across social media and, presumably, in actual conversation, liberal types have fretted over a thought: Soon, Donald Trump will begin getting intelligence briefings on issues of national security.

A man known to call reporters pretending to be his own press agent will be privy to America’s military secrets. The Donald, only with nuclear launch codes.

If that’s been a concern, you can exhale. The truth is more a mundane, but still fascinating glimpse into how a current government deals with the uncertainty of the electoral process. Like every other part of a presidential election, who gets to know what is a highly contested, intensely personal and ever-changing tradition.

The current protocol for intelligence briefings is this: In July, after each party’s convention, the presumed presidential nominees—Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton—will get an intelligence presentation. It’s a very long one, featuring several hours of top secret information, though maybe not as much as one might think. The real briefings don’t begin until after the general election in November, when there is a president-elect.

The nominee’s first, and only, briefing is less about tactical operations and more about seeing the world as it really is, officials have said. Candidates won’t be hearing about that night’s secret operation to assassinate a key ISIS leader. Think, rather, of an advanced social-studies seminar.

“You are not trying to give them a tactical update on the issues of the day, but to lay out the full panoply of issues that they are going to face; the good, the bad, and the ugly of what the world looks like and what implications there may be going forward,” a former intelligence official recently told the New York Times.

After the general election, though, the winning candidate does get daily briefings, if they so choose. Those include the President’s Daily Brief, which the sitting president gets every morning, a document that has been called the world’s smallest circulation, yet best-informed daily newspaper.

The briefings began under Harry Truman, who established the practice for the first time in 1952. It was a reaction to his own experience as president: when Truman took over following Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death in 1945, he knew next to nothing about the U.S.’s intelligence apparatus, including the fact that we were making an atomic bomb, according to John Helgerson’s CIA Briefings of Presidential Candidates.

Truman offered weekly briefings to Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower and his Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson after they were each nominated, though tensions between Eisenhower and Truman—who at one point referred to Eisenhower’s men as “screwballs”—meant they were nearly scuttled. But the briefings eventually took place, and each candidate got three or four before Eisenhower prevailed in November. By that point the briefings—which, in those days, were more infrequent—were mainly focused on the ongoing Korean War.

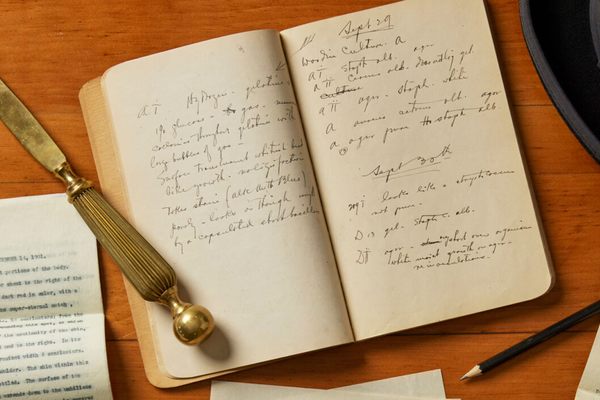

Nixon with Mao. (Photo: White House Photo Office/Public Domain)

In 1960, it was John F. Kennedy versus Richard Nixon, and, late in the campaign, the Kennedy camp released a statement urging U.S. support for Cuban freedom fighters. The only problem was that there was an ongoing top-secret CIA program going on doing just that. Did Kennedy know? Probably not, but it was the first time intelligence officials had to consider the implications of disclosing covert actions to candidates. (They never had, even to Presidents-elect.) After Kennedy’s election in 1960, he was given a full knowledge of the Bay of Pigs operation (which turned out to be a disaster.)

Since the inception of the program, the outgoing president has decided what information candidates get, and who gets it, which has traditionally been each nominee from the two major parties. (Ross Perot might have been the first non-Republican or non-Democrat to get briefings, but he dropped his independent campaign for president in July 1992 after polling well early in the campaign. No such other third-party candidate has come close.)

The briefings have also evolved over the years, from a helter-skelter system of scattershot information to the more focused thing it is today: one briefing as nominee, then daily briefings as president-elect. But history has also shown that, for all the information the general public assumes is in these top-secret briefings, we may not be missing all that much. Jimmy Carter, for example, complained that his briefings were sometimes too much like reading the New York Times.

Sometimes, the candidates themselves have not even received the briefings personally. In 1968, Richard Nixon’s key advisors also got it, including Henry Kissinger, who soon forced the briefings to go through him exclusively, excluding Nixon. Kissinger would then brief the president-elect personally, according to Helgerson.

Other candidates have been more hands on, like Jimmy Carter, who proved himself a voracious consumer of the briefings, which he was given a broad range of, since, in 1976, his opponent was President Gerald Ford. (Among Carter’s briefers was George H.W. Bush, then the Director of Central Intelligence, who asked Carter to stay on as director after Carter’s election. Carter declined, but joked later that had he said yes, Bush likely never would’ve become president.)

In contrast to Carter, Ronald Reagan, in 1980, was sometimes openly hostile to the briefings, complaining that he was given information that he could do nothing with, according to Helgerson. After his inauguration, Reagan closed off direct communication with CIA officers altogether, communicating solely with his handpicked CIA chief William Casey.

Clinton at his first inauguration. (Photo: White House Press Office/Public Domain)

The tradition of candidate briefings continued through the years, however, with a range of losers all getting a window into the U.S.’s intelligence operations. Walter Mondale, Michael Dukakis, Bob Dole, John Kerry, John McCain, and Mitt Romney all got some intelligence. It is, in other words, just another part of the job. Or, for some candidates, a chore. Or an afterthought. Or, occasionally, deeply fascinating.

“On one memorable day,” Helgerson, who was among those who personally briefed Bill Clinton, wrote of the then-candidate in 1992, “the hurried Governor was busy putting on his necktie and drinking a Diet Coke when we met for our session. He said he would not have time to read the book and asked that I simply tell him what was important. I gave him two-sentence summaries of a half-dozen items and one longer article in the [President’s Daily Brief.] When I finished this staccato account I expected the Governor to depart, but he said, ‘Well, that sounds interesting,’ seized the book, and sat down and read the whole thing. He had tied his necktie.”

Might Trump do something similar? We’ll know in November.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook