How Vodka Became a Currency in Russia

Since the 16th century, the spirit has been the country’s gold standard.

When Evgeniia Pletneva’s parents built their house in the 1990s, not far from St. Petersburg, Russia, nails, boards, and doors weren’t available in stores. So her mother hung handwritten fliers around town, listing the items they wanted and offering either vodka or money in exchange. Pletneva’s father, a sailor, had visited Germany and picked up five liters of Royal, a grain spirit with an astounding 96 percent alcohol (192 proof) that was then popular in Russia. The couple traded the booze for the materials they needed, throwing in a little cash for zakuski—snacks to be consumed while drinking.

Pletneva, who was around nine at the time, remembers helping her mom and sister carry one of the doors home. Exchanging alcohol for goods “didn’t seem weird, as many people were doing this,” she recalled in a text message. (Pletneva is a friend of the author.) Food was also in short supply, with long lines to purchase what remained on sparse grocery store shelves. “We knew that in villages people were taking vodka as a salary, as money was not really needed,” she added. “You couldn’t buy anything with that money.”

Using vodka instead of cash made sense when actual currency was almost worthless. As the USSR collapsed and hyperinflation soared, Russians referred to rubles as “wooden” money. Some stores stopped taking them entirely, accepting only American baksy, German marks, or British pounds. Shopkeepers priced their wares in dollars; after that was forbidden in 1993, they switched to “killed racoons,” slang derived from the Russian abbreviation for “conditional units,” a term for the equivalent of a dollar. Russians sought out hard currency for its stability and buying power. They also hoarded a product known to hold its value: vodka.

“I have more than 20 bottles at home, and I don’t drink at all,” a Moscow laboratory clerk named Dmitri Shmidrik told The Baltimore Sun in December 1991. This “liquid currency,” as he called it, played an essential role in everyday transactions. As the Sun explained, “A repairman will yawn if you offer 20 rubles to get the car fixed or a ceiling plugged. But if you offer a bottle of vodka, the job gets done.”

At the time, there was a shortage of the spirit, caused partly by hiccups in glass bottle production and a trade dispute with distilleries in neighboring Belarus. But even after the supply normalized, vodka underpinned the transition economy. Cash-strapped factories bartered it for materials, and the government even allowed some companies to pay their taxes in booze. In 1998, authorities in one Siberian district gave 8,000 school teachers 15 bottles apiece, in lieu of wages. The initial proposal, according to a UPI report, had been toilet paper and coffins, “but vodka is favored as the only thing that can be freely sold or exchanged for bread and other food.”

Stories like these made headlines in the Western press, illustrating the chaotic turn away from Communism. But vodka barter wasn’t just a product of perestroika; the practice had been going on for hundreds of years. As Mark Schrad writes in Vodka Politics: Alcohol, Autocracy, and the Secret History of the Russian State, “When times are tough, vodka has always been there—not just as a product to be bought to drown out one’s sorrows, but also as the currency used in the exchange.”

In the 16th century, Schrad explains, agricultural improvements produced booming harvests. Rather than bring their surplus grain to an oversaturated market, many Russian landowners distilled it into vodka, a higher-value product that was also easier to transport. With the tsar’s encouragement, the spirit became popular, replacing beer and mead as the peasants’ drink of choice. The harder stuff was more profitable at government-run taverns that generated revenue for the state. (A museum in St. Petersburg, the Russian Vodka Museum, tracks this history with a large collection of bottles, stoppers, and glasses.)

In rural areas of the Russian Empire, vodka served as compensation for manual labor through a practice called pomoch’, which translates literally to “help.” Farmers mustered the extra hands they needed by offering food during the workday and a banquet afterwards, at which vodka flowed. As the late historian Patricia Herilhy noted in her 1991 paper Joy of the Rus’: Rites and Rituals of Russian Drinking, pomoch’ was framed as a tradition of mutual support, but could also have an exploitative bent. For wealthy farmers, a decent spread and a bucket of vodka were cheaper than paying 20 to 30 poorer villagers in cash. Plenty of workers got hammered at these banquets, but some poured their share of booze into bottles and took it home. The vodka was “the only part of the day’s pay that could be kept,” Herlihy wrote.

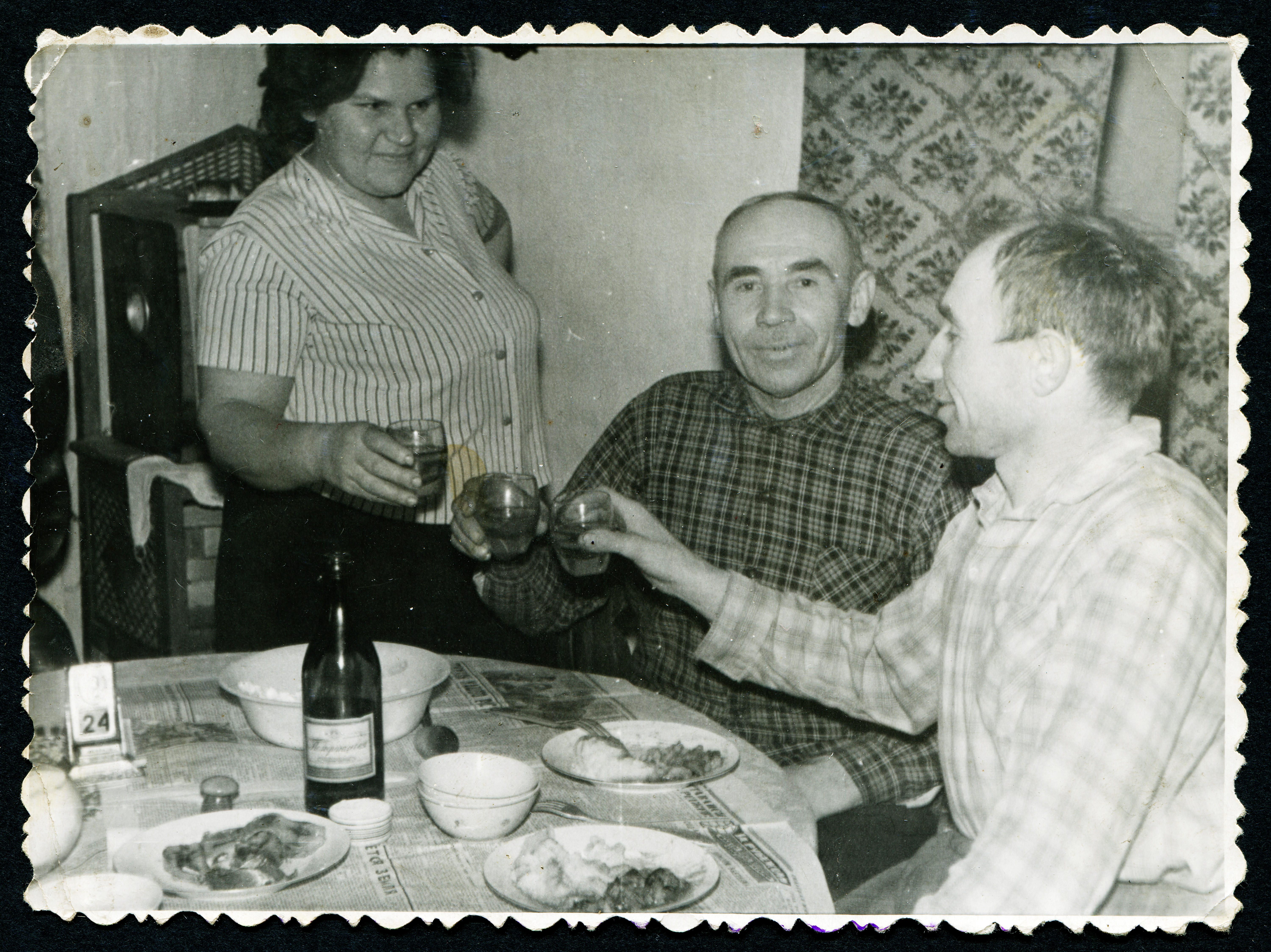

The tradition of food and drink in exchange for service carried into the 20th century. Sergei Sotnikov, an interpreter in Moscow (and a former colleague of the author), recalls how his family built a house in 1970s Ukraine, which was then a Soviet republic. His dad’s friends and coworkers helped with the construction; in return, they got dinner and vodka or samogon, home-brewed moonshine. “It would have been very strange if they had said they wanted money,” Sotnikov writes in an email. As a kid, he was sent to a bar with two three-liter glass jars to have them filled with beer for the group. (A note from his father was sufficient for the barkeep to give alcohol to a 12-year-old.) “That was how people lived then.”

Pavel Syutkin, co-author with his wife Olga of CCCP Cook Book: True Stories of Soviet Cuisine, writes in an email that women in particular relied on vodka to get the help they needed from men after the Second World War. Olga’s grandmother always kept vodka on hand in the ’70s, Syutkin says, “sometimes to pour a glass for a neighbor for helping to bring coal from the cellar, sometimes to a friend who fixed the hinge.” She’d “spend” about one bottle per month on services like these. Those who couldn’t afford to buy vodka for this purpose had to brew their own samogon.

Alcohol was preferred payment for small tasks, Syutkin says, because “it was not a shame to offer a little portion.” Handing someone a single ruble for their work might be seen as humiliating, but “to pour 150 grams of vodka on the same ruble and to serve a sandwich with lard—the guest is pleased, and of little burden to your budget,” he says.

Vodka was a handy medium for the informal, often illegal transactions necessary to survive under Communism. As the anthropologist Myriam Hivon described in her 1994 paper Vodka: The “Spirit” of Exchange, a worker at a collective farm might “sell” a ton of state-owned manure to a villager for private use in exchange for two bottles of booze. For under-the-table deals like these, Syutkin says, vodka was less incriminating than using money. In other cases, “paying” someone in alcohol actually helped you play by the rules. By trading a bottle for assistance ploughing land, for example, a person could get their needs met without running afoul of Soviet laws that prohibited hiring private help, Hivon wrote.

Today, the repairman expects to be paid money. But the concept of booze as a store of value persists. In 2014, the ruble took another nosedive amidst falling oil prices, conflict in Ukraine, and Western sanctions over Russia’s invasion of the Crimean peninsula. Things got so bad that the Russian government lowered the minimum price for vodka. A brand called “Russkaya Valyuta,” which translates to “Russian Currency,” quickly became one of the country’s top sellers.

You can join the conversation about this and other Spirits Week stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook