The Ocean’s Largest Shark Has a Little Something to Say

An online video raised a strange question: Do whale sharks make sounds? And would it matter if they did?

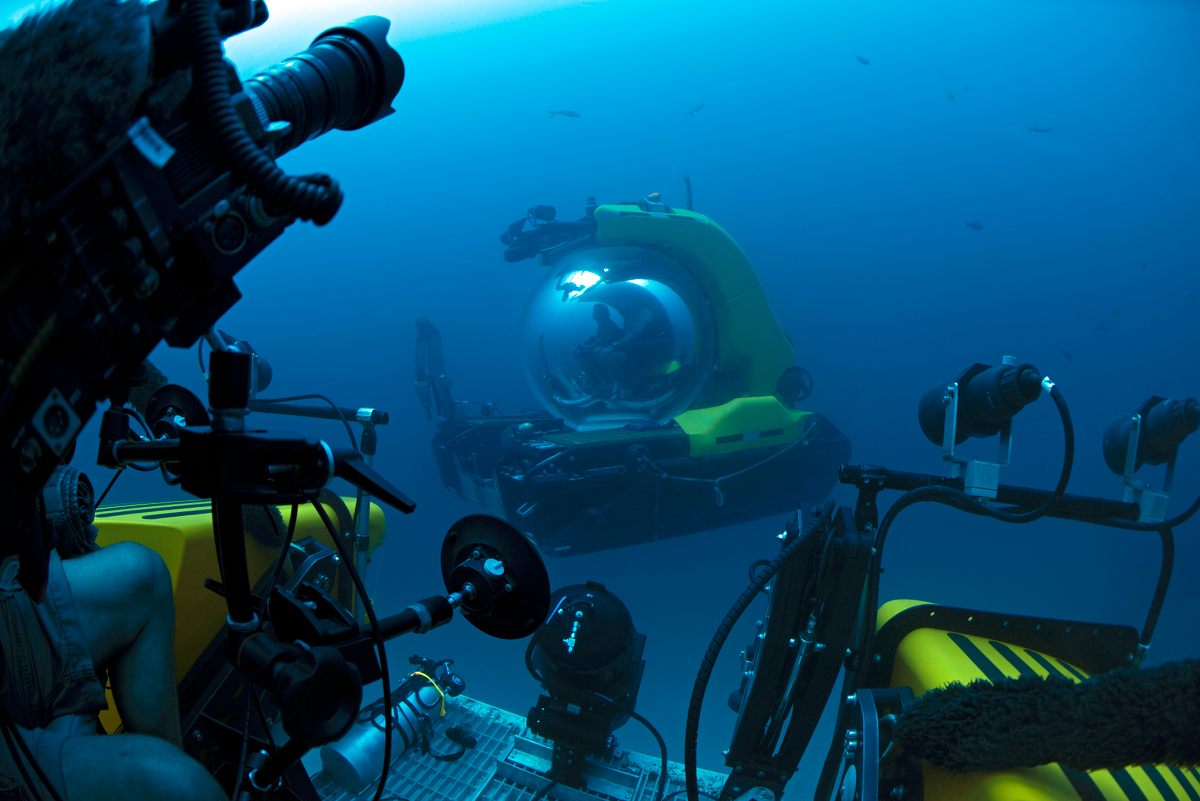

Jonathan Green first heard the sound late at night during the summer of 2016, while watching 10 hours of a whale shark swimming through open ocean. Green was reviewing footage captured by a camera that had been stuck temporarily to the whale shark’s head, which he and his team had put in place to film for the BBC’s Blue Planet II documentary series.

Around 11 p.m., after hours of hearing nothing but the hiss of water passing by the camera, he had the volume turned down. Then he heard something unusual: a “low, gravelly whisper.” He hit rewind and turned the volume up. Then he woke up the rest of his team.

The crew sat together in silence as he played the sound over a bluetooth speaker, over and over.

“We were thinking, okay, this has gotta be mechanical, it can’t be coming from the whale shark. But it doesn’t sound mechanical,” Green says. “We just sat there and thought: What the hell are we listening to?”

The video is filmed from just in front of the animal’s dorsal fin, providing a first-person perspective of the largest fish alive. The whale shark was swimming near Darwin’s Arch, an inverted stone U thrusting out of the Pacific Ocean, chalky white and red-brown against deep blue. Just beyond that is Darwin Island, a high, grassy plateau that drops into vertical cliffs. This remote outpost sits roughly 100 miles north-northwest of the Galápagos Islands, where Charles Darwin did his famous work.

Darwin himself never came here, as there was nowhere dry to land. But if he had stuck his seasick face into the ocean here, he might have delighted in the profusion of life around these places named in his honor. Green and hawksbill turtles, manta rays, fur seals, dolphins, yellowfin tuna, and fish in all colors and sizes call the food-rich waters around Darwin’s Arch home—as do sharks in their multitudes. This area is said to have the highest concentration of sharks in the world: silky sharks, Galapagos sharks, tiger sharks, whitetip and blacktip reef sharks, schools of scalloped hammerheads, and whale sharks, which return to the Galapagos every year from June through November. Though whale sharks grow as large as a yellow school bus (and the largest measured was bigger than a semi-tractor trailer), these massive animals are filter feeders, and they come to the Galapagos to vacuum up the small fish and plankton that bloom there in abundance every summer. (They also might come here to have their babies—but that’s another story.)

You don’t see much of Darwin’s richness in Green’s video. Mostly, you see the blue-green gradient of open ocean and the whale shark’s massive, spotted head, swaying as it swims. Then, there’s the sound: two pulses of a rough, rasping groan, one long and one short. The camera shakes slightly; there’s a click, and then another brief groan, lower and quieter. Just after the sound trails off, you can see a smaller shark species swim up from beneath the spotted head, flashing its pale belly after brushing against the whale shark’s underside.

Here’s the thing about the sharks: as a general rule, they don’t make sounds. Across sharks’ 400-500 species, no one has ever found an organ even capable of making sound. (The closest is a New Zealand shark that “barks” by expelling water.) So after it was captured, the BBC team sent this video to be reviewed by multiple experts. None could tell them what exactly they were hearing.

Green thinks it’s unlikely that the sound came from a boat; Darwin Island is an extremely remote location, where few other boats venture, and based on the video’s time stamp, his own boat wasn’t running at the time. But the experts couldn’t even say whether the sound was natural or man-made.

“At the 11th hour [the BBC] said no, scientifically, we can’t air this noise until we confirm what it is,” Green says. “They even recorded something with David Attenborough. Much to our disappointment they had to pull it.”

For years, the video sat in a file on Green’s computer. Then, in the summer of 2019, he decided to post it on the Facebook page of the Galápagos Whale Shark Project, the research organization he leads. He saw it as a way to get the sharks some much-needed attention: In 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) changed the whale shark’s global status from “Vulnerable” to “Endangered.” With their global population decreasing, whale sharks needed every bit of public awareness they could get.

In his video, Green dubbed the sound the “Dino Roar,” an homage to the fact that whale sharks’ ancestors swam our prehistoric seas nearly 60 million years ago, just after the fall of the dinosaurs. The response was enthusiastic. Galápagos Whale Shark Project normally gets around a thousand views on its Facebook videos; to date, the Dino Roar video has gotten over 12,700.

But the video did more than just catch the public’s eye. It has also connected Green with whale shark researchers who had stories of their own.

Within an hour of the Galápagos video being posted on Facebook, Heather Barrett started getting a lot of notifications. She had been tagged in the video by friends three separate times. Not long after, she got in touch with Green by email to share her own experiences, from over three years investigating unusual sounds around whale sharks.

Barrett was an undergraduate student when it started. At the time, she was volunteering for a research project on Mexico’s Bahia de los Angeles. Perched beside the cyan waters of the Gulf of California, the remote research station where she spent the summer of 2010 could only be reached by three days of driving through stark desert, studded with cacti and extinct volcanoes. It was perfect for studying whale sharks. Every summer, massive blooms of tiny plankton drew hundreds of whale sharks to the shallow, protected bay.

Snorkeling beside the sharks, Barrett’s job was to photograph each animal’s pattern of spots—each one unique, like a fingerprint—for a catalog documenting the individuals that visited the region every year. Every third day or so, she estimates, she began noticing a strange noise in the water around them.

During her photo ID swims, Barrett started taking videos, hoping she might catch the sound on camera. After a couple of attempts, she got one: two pulses of a short, harsh rattle, picked up while swimming next to a scarred 12-foot male named Shredder. She thought it sounded like two strokes over the ridged back of those wooden frog noisemakers sold to tourists in every Mexican market.

It was the only video that Barrett managed to capture that summer, but she was determined to keep trying. That winter, the sounds “became a bit of an obsession,” she says. She knew there was nothing yet that showed they had anything to do with whale sharks. But Barrett had grown up in a family of scientists, taught from childhood to pursue out-of-the-box questions—and she thought this question was compelling enough that it might make a good subject for a Master’s thesis.

She started designing a research project, and found someone who would loan her a basic recording device. But when she reached out to experts for advice, making “a lot of cold calls and emails, trying to get my foot in the door to learn about acoustics and shark physiology,” Barrett hit a snag.

“When you start going to a shark biologist about possible sound production … I feel like it was very discouraging,” she says. “I got a lot of ‘no’s, got a lot of laughter, a lot of, ‘Why would you focus on that?’”

Barrett had expected skepticism from the shark community; sharks don’t have vocal cords, so they can’t make sounds in the way whales, seals, or humans do. They also don’t appear to have the ability to make sound in the way that some particularly vocal fish do. Their rows of tiny vestigial teeth aren’t large enough to grind together. They also don’t have swim bladders, which some fish use to control their buoyancy, to drum up against.

“It is fair, for people to be very skeptical,” says Barrett. Looking back, she understands that these researchers were evaluating whether her left-field question was worth dedicating time and money to. She wonders if some were trying to protect her, still early in her career, from wasting her reputation and her time.

“I realized it pushed questions out of our current box,” Barrett says. “Asking that question was hard for people because the box was safe. More funding comes from the box, there’s less risk in the box.”

Barrett was able to go down to Bahia de los Angeles twice more, in the summers of 2011 and 2012. Swimming in those crystal waters, she gathered a small library of the short croaking sounds, just like those she had first heard next to Shredder.

She also captured one additional, particularly intriguing recording. In 2011, just as a storm was moving in over the boat, Barrett managed to get her recorder in the water during a feeding frenzy. At least eight to 10 whale sharks were feeding on a ball of baitfish, alongside sea lions and diving clusters of blue-footed boobies. The resulting recording sounds something like a woodland pond in the thick of summer, with frogs calling from every direction: a layered series of drum-like pulses, sounding off at different volumes, almost like they were coming from different individuals.

Not long after that trip, however, Barrett realized she had to move on. No one she spoke to wanted to focus on potential whale shark sounds. So she applied to graduate school under a different project, focusing on sea otters. She made one more attempt to record the sounds in 2016, but the weather didn’t cooperate, and she went home empty-handed.

“Maybe I was being naive and youthful, but it was not realistic to keep it up and fund it,” she says of the project. “[To do this project] would be multifaceted, and expensive, and involve lots of collaboration. But what it comes down to and what I was met with a lot of times is, people are like, ‘Who cares?’”

Barrett and Green’s stories invite that very question. In the relatively small world of whale shark research, experiences with, and opinions on, odd sounds run the gamut.

“You would think we would have heard it,” says Dr. Alastair Dove. Dove is Vice President of Research and Conservation at the Georgia Aquarium, one of the few places in the world that keeps whale sharks in captivity. “We have four at the aquarium. People are diving with those sharks every day. I’ve been in there dozens of times. And we’ve never heard those animals make any detectable noise.”

Marina Padilla, a marine biologist who guides tours with the company Baja Charters in La Paz, Mexico, has been in the water with them nearly every day during whale shark season for the past five years. She had no croaking, grunting, or purring to report—but she did say that one of her coworkers had heard such sounds.

Dr. Dení Ramírez Macías, the director of Tiburón Ballena México (Whale Shark Mexico), has been studying whale sharks since 2001 and is currently focusing on the population in the Gulf of California. Macías noticed unexplained sounds around whale sharks from the very beginning; while doing her PhD in the Caribbean, she remembered one large male shark who seemed to make a sound every time she and her teammates jumped in the water around him.

Macías compared the sounds she’s heard with the rapid knocking or clicking vocalizations made by sperm whales.

“You feel where the sound comes from,” Macías says. “To me, it’s pretty evident that it comes from the shark and not from a boat.”

Rafael de la Parra, Executive Director of the research organization Ch’ooj Ajauil AC in Quintana Roo, Mexico, has a similar tale. For 17 years he’s been studying a massive aggregation of whale sharks (thought to be the largest in the world) that come to the Caribbean annually.

“We are almost terribly sure we’ve been listening to some kind of roar, or purring, like a big cat purring,” de la Parra says. “One of my children, who has been working and collaborating with us, he used to say when we listened sometimes: ‘Did you hear that, she was singing to us!’”

What these stories share with each other, and with Barrett’s experiences, is a description of a seemingly similar sound: a low, rapid vibration. What they also all share is an air of careful skepticism.

“We have to be quite careful about saying it was the whale shark,” says de la Parra. He points out that many whale sharks are surrounded by an entourage of fish that follow everywhere, using the shark’s bulk for protection and scavenging any bits of food the shark misses. “As long as any of these fish have a swim bladder, they are in theory able to produce sound.”

Several researchers also noted that whale sharks often ingest air when they feed at the surface, and that you can see bubbles emerging from their gills after a big gulp of plankton. The sounds might therefore be nothing more than escaping air—like a very large, underwater burp.

If it were proven that whale sharks made sounds intentionally, that would be another story. Researchers agreed that, if these sounds did have a function, whale sharks would face being drowned out by human noise in an increasingly noisy ocean. That’s already becoming a problem for other species.

Plus, “with these very vocal animals like whales, sound production is very much linked to social behavior,” says Dove. “It implies there’s some higher level of cognitive function. If whale sharks are talking to each other, maybe they’re more social than we thought.”

Dove doesn’t completely dismiss investigating the concept. He was part of the team that helped place the BBC camera on the “Dino Roar” shark, and still finds the video fascinating. What interests him most is the sound’s timing. “There’s an awful lot of swimming around in the blue on the video, and that sound coincides with the one time a shark happens to swim up near [the whale shark],” Dove says. That could mean that the sound was voluntary, a reaction to the smaller shark.

But perhaps the most common view among researchers is that, though these sounds might be interesting, they’re dwarfed by much bigger issues. There are so many fundamental questions left to answer about whale sharks that these sounds fall to the bottom of the list.

As Macías put it: “At least from my point of view, it’s been a small curiosity rather than a major focus.”

Green himself feels this pressure acutely. “We have to focus our work on very specific areas,” he says. For instance, though his video might have spurred other conversations about whale shark sounds, he doesn’t anticipate looking into the sounds anytime soon. His team’s next two years focus on investigating whether whale sharks do indeed give birth around the Galápagos.

He added: “Audio is not the priority, because it’s not going to help in the long term with conservation.”

After talking to whale shark researchers, it’s easy to see why these sounds haven’t made it past the curiosity phase. They speak to the very nature of how risk and compromise work in science. How do you choose to pursue the out-of-the-box questions, the left-field curiosities, when doing so would require a massive leap? And how do you take that leap when it’s over a chasm filled with questions that are just as, if not more, important?

Perhaps the best way may be a baby step rather than a leap. Barrett’s original plan for her recordings was to publish a short communication called a biological note, which doesn’t require the amount of data needed for a full scientific paper. Since watching Green’s video, she’s resolved to revisit, and eventually publish, the draft she started years ago. With the help of an acoustician, she plans to focus the note on the sounds themselves, rather than the controversial possibility that they are coming from whale sharks.

“In 2020 I want to dust it off, and talk to some people that could really help me,” she says. “That way, if anyone is ever able to get funding, it’s listed somewhere, to say: This occurred, this could be an interesting question.”

Worldwide, whale shark numbers are thought to be decreasing due to pollution, ship strikes, and accidental injuries in fishing nets, as well as some targeted hunting that still happens for the shark fin soup trade. The effects of climate change are also a growing concern.

That knowledge adds a sense of urgency to the questions that remain about whale sharks. Whether they are purring or bubbling or just cruising silently through the blue, it’s clear these gentle giants have even greater depths than we’ve yet plumbed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook